Since I’m back in Star City for some Orlan training in the Hydrolab, I thought it’s a good time to share Part 3 of my “Star City Impressions”. See here for Part 1. And here for Part 2. Part 3 is about a day in the Hydrolab last spring with fellow Shenanigan Alex.

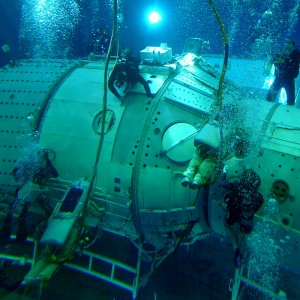

Star City’s pool is called Hydrolab (Гидролаб). Just like the giant Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory in Houston or the smaller Neutral Buoyancy Facility in Cologne, the Hydrolab has one purpose: conjuring up weightlessness to train astronauts for extravehicular activities (EVAs). The circular pool houses real size replicas of the Russian modules of the ISS, with one unique ingenious feature: the mock-ups do not stand on the pool floor, but rather on a mobile platform that can be raised above the water surface in a few minutes. From my spacewalking training in Houston, I’m accustomed to explore the Station in scuba gear prior to a training run in the EVA suit, but being able to step on the platform and just walk around the modules, even climb inside the airlock, is a pleasantly different experience. In fact, it’s almost surreal: during my training in Houston I have learned to perceive myself as if in space when moving around the ISS replica. Here in the Hydrolab the visual clues are very similar: the cylindrical modules, the handrails, the antennas, the cables… everything contributes to summon up that feeling of being outside the Station. And yet I’m standing on my feet.

Alex and I take a quick final look at today’s translation path with our instructor Valery, then we head to the crew room to gear up for the run, while the Hydrolab staff starts to lower the platform into the water. The crew changing room is furnished in that peculiar Star City style, so different from the colder, down-to-business character of European or American facilities: a large soft couch with a gloomy leafy motive along the wall, a long wooden table in the centre and flowery carpets on the floor of the small changing areas delimited by two shaky canvas screens. Three nurses in white coats are in charge of operations in the room. First they assist us in putting on the medical belt with the heart rate and breathing frequency sensors. Then they direct us to don the water cooling undergarment, a brightly blue, tight-fitting mesh overall with tiny tubes woven in the fabric: to remove body heat generated through physical exertion, cooling water is circulated in the tubes. In space, the water is cooled via a sublimator. In the pool, we simply receive fresh cooling water continuously from the surface via the umbilical.

After seeing the doctor, stepping on a scale and sitting still for a few minutes to record resting measurements from the medical belt, Alex and I head back out to the poolside, where our Orlan suits are ready to be donned. Contrary to NASA’s EMU suit, whose final assembly occurs during the donning process itself, the Orlan is already in one piece, with access provided by the entire back side of the rigid torso pivoting open like a door. In the space version of the suit, the back door contains most elements of the life support system, from the oxygen bottles to the CO2 scrubbing cartridge. In the hydrolab suit, on the other hand, the back door houses the emergency air supply. If air flow from the surface via the umbilicals was ever interrupted, cosmonauts themselves could switch to emergency air bottles by flipping a lever in the front of the suit.

Sitting briefly on the frame of the back door Alex and I put on our communication cap, which includes microphone and headset, connect the water lines and the medical belt cable and slide into our respective suits. The back door is closed behind us. The Orlan is one-size-fits-all and I’m pretty much at the lower end of the anthropometric dimensions that can be accommodated by folding up arms and legs. Still, when I enter the unpressurized suit I can’t stretch out to my full height. This is intentional: as I slowly rotate the regulator, the overpressure inside the suit increases and I feel the suit expanding, the soft membranes around my arms and legs becoming rigid walls.

The Hydrolab version of the Orlan doesn’t have the computer unit, but I can monitor the delta pressure on the analogue gauge: the nominal overpressure is about 0.4 atmospheres, quite higher than what I’m used to from NASA’s EMU suit. In part because of the different construction and in part because of the higher delta pressure, working in the Orlan promises to be quite a physical challenge.

Once in the water, the safety divers take charge of us and bring us to the bottom of the pool to work on our weight: adding or removing weights from different locations on the suit, they make us as neutrally buoyant as possible. Then we’re brought to the airlock, where we set up our initial tether configuration for hatch opening. From this point on, we are in “space”, solely dependent on our hands to move along structure.

According to the briefed plan, Alex and I perform normal and contingency hatch operations, translate across the service module carrying a bag, work with small tools and electrical connectors, operate the Strela crane and perform a simulated rescue of each other. Under the watchful eye of our instructor, who observes us through the window in the pool wall and via the floating cameras, we become familiar with the Russian tethering protocol: no reeling safety tether, which is used in US spacewalks, but two tethers permanently attached to the suit and used “via ferrata” style throughout the run, with the cogent requirement of always having them attached to different handrails or holding on with one hand when moving a tether from one handrail to the next.

After four hours of intense work my hands are exhausted from the hundreds of hook actuations in the rigid and somewhat oversized gloves. Yet, as always, the biggest challenges offer the greatest gratification. Alex and I have begun to learn how to operate in the Orlan suit and have gained some initial appreciation of the peculiarities and difficulties of performing spacewalks on the Russian segment of the Station. I might or might not have a chance to wear an Orlan suit in open space – and I will need a lot more training to be ready. But for the moment I enjoy that distinct pleasure derived from having learned something new, while I sip the cup of hot tea thoughtfully prepared by the nurses, sitting on that soft big couch with the old-fashioned leafy motive, still in my water cooling undergarment.

More photos on Flickr in the Orlan set and the Hydrolab set.

Discussion: 8 comments

I think every space facility needs a cushy couch. 🙂 Awesome blog entry — it’s fascinating to read how the different countries do things, and where processes are similar and different.

Thanks for your feedback, glad you enjoyed it 🙂

So cool! Great article Samantha.

I’m wondering if you experience some reflexes to do “swimming” motions. Because of feeling the water friction and density it must be tempting to just waive your legs and arms to move around. But don’t do it, hehe. It won’t work up there.

I wish you luck!

It’s tempting, indeed! But as you can imagine instructors don’t let us do that. Thanks for the nice feedback!

Excellent write up Samantha, I enjoyed this thoroughly. What are the minimum and maximum heights for fitting in the suit? Is this type of training dangerous?

Thanks!

Cahal

Hi, thanks for the nice feedback. My height, which is 165 cm, is considered the minimum height. The maximum one is 190 or 195, I don’t remember exactly.

It’s a training environment to be taken seriously, of course, but I wouldn’t call it dangerous.

Cheers,

Samantha

preparacion debe ser muy agotadora el trabajo en el espacio por la falta de gravedad es acaso mejor o mas ligero GRACIAS CAPITANO DESDE LIMA PERU

ESTANDO NOVIEMBRE CADA VEZ MAS CERCA TODA LA BUENA FORTUNA PARA UD SAMANTHA ES MARAVILLOSA LA TECNOLOGIA Y LA VALENTIA DI LEI CAPITAN AUGURI