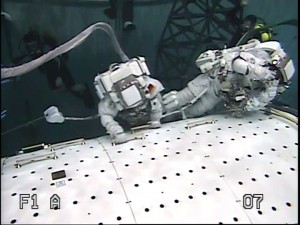

Fellow ESA astronaut Alexander Gerst bringing “unconscious” crewmate Reid Wiseman back to the airlock during a practice rescue scenario in the NBL (Photo courtesy Alexander Gerst)

There are also specific risks inherent to a spacewalk and one of the most dreaded scenarios involves a spacewalker going unconscious due to a medical issue or a malfunction of the pressurized suit. Over 150 spacewalks have been performed to assemble the Space Station and such a dramatic scenario has never occurred. However, you will not be surprised to hear that it does materialize quite often during training in the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory (NBL).

During the EVA training flow future crewmembers are required to demonstrate the ability to rescue an unconscious fellow spacewalker by bringing him or her safely back into the airlock within 30 minutes. I had a chance to try the rescue for the first time last Thursday during a six-hour run in the NBL with veteran spacewalker Steven Swanson (Swanny).

Ready to be lowered into the water for an NBL training run. Notice lying on the floor the reel of an 85-foot safety tether. The big hook attached in front is connected to structure after airlock egress, while the reel follows along.

Safety tethers, on the other hand, are thin steel cables that are coiled in a reel. We attach one end to structure as soon as we exit the airlock, and since we carry the reel with us, the cable uncoils as we move away and recoils when we come back. If we need to go far out on the truss, we might even have to carry a second safety tether to attach when the first one runs out, and having to make the swap on the way back with an unconscious crewmate would require extra precious time.

But it was not the case for me on my first try. I merely had to detach Swanny’s local tether and use it secure him to myself, and then stow his safety tether, since we would be both secured by mine. Sounds quick and easy, right? Well, I guess it could have been. In reality, when I was ready to move, I realized that I had created a tether tangle and I would have to take the time to fix it if I was going to go anywhere. Good lesson learned!

ESA astronaut colleague Christer Fuglesang stands on a platform at the end of the Station's robotic arm, Canadarm2, during operations to relocate a CETA cart on the ISS (Credit: NASA)

For a scheduling coincidence, I had my first rescue scenario as a robotic operator the very next day. When EVA crewmembers are attached to the Space Station Robotic Manipulator System, or Canadarm 2, they must count on the robotic operator to bring them quickly and safely back to structure in case of an emergency. One more skill I’ll be trying to acquire in the next few weeks, but the details are for another day…

Discussion: 3 comments

I’d must test with you here. Which is not something I often do! I take pleasure in studying a submit that will make people think. Also, thanks for permitting me to remark!

It migh be weird to say it, but this definitely makes me dream! Well, of course not the fainting part, as fake as it was, but the EVA rescue training one… a thing I wish I can try one day (as far as it is an exercise… don’t know if I would be that happy if it actually happens in space…)!

This sounds so challenging – how often do you train physically during a week to be able to keep up with having to do such strenuous tasks?! Is there any way to perform medical procedures on crewmembers during space walks before you get to the airlock?