Update: scroll down to question 20 for new answers!

Thanks for all your comments and questions on social media, your interest is just fantastic. I’ve answered some of the most commonly asked questions, and listed them here. I’ll try to answer more, but before posting new questions, please check through these to make sure I’ve not already covered that topic.

1) What time zone do we use in space?

The Space Station runs to UTC (Universal Time Coordinated), which is basically GMT, luckily for ESA and those of you in UK. This time zone was chosen because it’s ‘in the middle’ of all the International Space Station partners (USA, Canada, ESA, Russia and Japan) and each of the two main mission control centres, Houston and Moscow, gets to cover half a day shift.

2) Do we all sleep at the same time, and what time do we go to bed?

Yes, we sleep pretty much all at the same time. We try to get about 8 hours of sleep per night, but this varies and we can go to bed anytime from 10 p.m. to midnight. I usually wake up at 6:30 a.m., which gives me time to prepare for the day’s activities. While we’re sleeping, mission control centres are monitoring the ISS systems. In case of an emergency, the ISS alarm would wake the crew and the Station Commander also has a radio speaker in their crew quarters.

3) Is there gravity in space, and why do we appear ‘weightless’?

This is a very common misconception that there is no gravity in space. Gravity is everywhere in space! It’s what keeps the Moon in orbit around Earth, it keeps Earth in orbit about the Sun and holds galaxies together. So, why don’t the Space Station or satellites fall to Earth, and why do we appear to be floating in the Space Station? That is because of our speed. We are not floating, we are actually ‘falling’. But we do not fall to Earth because of our high speed, we fall ‘around’ Earth. We travel about 28 000 km/h (17 500 mph) but as we accelerate towards Earth under the pull of gravity, Earth curves away beneath us and we never get any closer. Since we have the same acceleration as the Space Station, we feel ‘weightless’.

4) What does it feel like to float in space?

Floating in space is the most incredible feeling. It’s actually very liberating not to be held down by Earth’s gravity. I can look at something in the ISS ‘ceiling’ and just pop up there, turn upside down, pick it up, do a somersault and come back down again. We can store items on the walls and overhead without worrying about them falling down (Velcro is your friend here). It takes a while to get used to weightlessness and moving efficiently around the Station – but once mastered you can move around quickly with just the smallest of pushes. Imagine being able to travel down a long corridor on Earth without any effort – it would be great! We hardly use the soles of our feet at all – and because of this they become very smooth and soft – but we are constantly using the tops of our feet to grab under handrails and hold us down and so the skin becomes rough and hard on the tops of our toes.

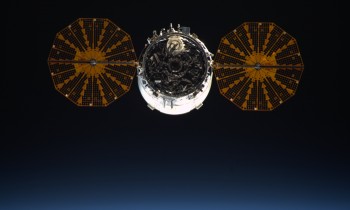

Same t-shirt as two pictures above – picture taken four days ealier (practicing Cygnus berthing). Credits: ESA/NASA

5) How do we wash our clothes in space?

We do not have a washing machine so we wear the same clothes, including underwear, for several days before we change. It is not as bad as it sounds. We live in a temperature-controlled environment, so clothes do not get as dirty as they might on Earth. Some of the items, like socks or our exercise gear, have anti-bacterial materials in them. We change our exercise kit every 7 days. We change underwear every few days. Then we have polo shirts, T-shirts, trousers and shorts that last weeks. I’m still wearing the same pair of trousers I’ve worn since day 1… hmm maybe it’s time for a change!

6) How do we cut our hair and shave in space?

We use a set of standard hair clippers for cutting hair. The only modification is that it is connected to a vacuum cleaner to suck up all the hair. I’ve been cutting my own hair just for fun and it’s working out OK, but not something I will continue to do on Earth! For shaving, we use either electric razors, or regular razors with shaving cream. In using a regular razor though, you have to wipe the shaving cream off on a piece of tissue quite often. When using the electric, we shave in front of an air filter, and this catches the stray whiskers! I have a wet shave at the weekends and use an electric during the week.

7) What happens to waste from the Space Station?

Our used and dirty clothes are placed in a waste bag and put on a supply spacecraft (Progress or Cygnus) that undocks and then burns up in Earth’s atmosphere. This is also how we get rid of other rubbish, such as empty food packaging or our solid waste from the toilet, for example. We don’t get rid of urine – that is recycled back into drinking water.

8) Can I see stars and planets, and do they look different?

Yes, we can see stars and planets. We still see some twinkling of stars because of the vast amount of gas/dust in the Universe that starlight passes through. However, our atmosphere causes most of that ‘twinkling’ and makes the stars appear slightly less clear than when viewed from space. That’s why you find many of the world’s observatories on mountains tops – it’s an attempt to reduce the amount of atmosphere that starlight has to travel through (and mountains tend to have less light pollution!).

Of course, we have no atmosphere outside our window, so it seems to me that the planets appear to be slightly brighter when viewed from up here – certainly Jupiter, Mars and Venus. What’s also interesting is trying to judge distance. When Cygnus departed in February, we had the most spectacular view of it disappearing ahead of the Space Station and of course it got smaller as it got further away but it still looked very sharp and clear even at a distance, because there were no atmospheric obscurants in between. This made it harder to judge how far away it was.

9) Why are there no stars in my pics of Earth or my spacewalk?

The reason why you can’t see stars in my daytime pics of Earth or my spacewalk is that, when lit by the Sun, any foreground objects, such as Earth, the Space Station or my spacesuit, are many thousands of times brighter than the stars in the background. Earth is so bright that it swamps out most if not all of the stars. The stars don’t show up because the camera cannot gather enough of their light in a short exposure. Our eyes are a lot more sensitive to light than the cameras. To take pictures of stars, we need longer exposures on night-time parts of our orbit.

10) How many times will we go around Earth during our flight?

You can work this out for yourselves. First, you need to know how long we’ll be in space. Let’s say 170 days. Then you have to know that we have 16 orbits every day. So that’s 170 x 16 = 2720 orbits.

11) How far will we travel during our time in space?

You know that we travel at 28000 km/h. Then you need to work out how many hours there are in 170 days. The distance will be 170 x 24 x 28000 = 114 240 000 km.

12) How long does it takes to get to the Space Station?

It takes a thrilling 8 minutes and 48 seconds to be launched into space on our Soyuz rocket. Once in space we have to do a few things. First, we have to ‘normalise’ our orbit because it will be elliptical after insertion and we need to make it more circular. Then we need to raise our height up to about 400 km using something called a ‘Hohmann transfer’ and then we need to put the brakes on so that we match the ISS speed and height perfectly in time for docking. This all takes about six hours from launch.

13) Why don’t you need a heat shield when leaving Earth, but only on reentry?

During launch, we gain altitude at relatively low velocity at first, but by the time we hit the high Mach numbers, we’re already in space so there’s no air to cause frictional heating. During reentry, we have no choice but to use the atmosphere to slow us down, all the way from Mach 25 (28000 km/h), and that creates a lot of heat.

14) Did you always want to be an astronaut??

As a young boy I was always fascinated by the stars and the Universe. When it came to a career choice though I was passionate about flying and could not wait to train as a pilot. I spent 18 years flying all types of helicopters and aircraft and eventually trained as a test pilot. I followed the space programme closely and when the European Space Agency held its selection for astronauts in 2008 I was ideally placed to apply.

15) What food do you eat in space??

We eat fairly normal food, like you might eat on Earth, but it is out of cans or packets. Some of it is dried food to which we add water to make it edible. Other (irradiated) food comes in pouches which we place in our electrical food heater to warm up. It’s not too bad, but we try not to eat too much salt in space as it can exacerbate the loss of bone density and so the food can sometimes be a bit bland. The portions are also quite small so you have to be careful not to lose too much weight… a great excuse for eating dessert every night! My favourite foods are the breakfast menus (scrambled eggs, baked beans and sausages!). We also get a very small supply of fresh fruit every so often on the supply spacecraft.

16) How can you eat food in weightlessness? Doesn’t it float back up?

You can swallow and digest food just fine in space. Digestion relies on different muscles in your body that squeeze behind the food you eat, pushing it through you until it’s safely in your stomach. This is called ‘peristalsis’. Once the food is in your stomach, you have various valves that keep food in place. However, after a meal you can definitely feel that your food sits more ‘lightly’ in your stomach and I learnt the hard way that you shouldn’t run on the treadmill for at least an hour or two after eating!

17) Is it true that you lose your appetite in space?

Not really, but the sense of smell is incredibly important when it comes to both generating a desire to eat and tasting food. In weightlessness, food aromas don’t hang around in the same way they do on Earth. Salt and pepper (which are suspended in liquid to stop the particles floating away), and other condiments are used to enhance the flavour. But our ability to taste food is affected in another way. Because fluids inside us shift towards the centre of our bodies and, in particular, our heads, we get tend to feel like we have stuffy noses, making it more difficult to smell food.

18) What would happen if someone got sick or injured in space?

All astronauts are trained to a very high level in first aid. In addition, there are always at least two Crew Medical Officers (CMOs) on board that can deal with basic surgical procedures, such as filling teeth or suturing, for example. Both Tim Kopra and I are trained CMOs. We also have a medicine cabinet, which is like a small pharmacy, containing everything from analgesic painkillers and antihistamines to sleep aids, all the way up to antibiotics and local anaesthetics. We also have an Automated External Defibrillator (AED) on board for resuscitation and we have procedures that include using a spacesuit as a personal pressure chamber if we needed to treat a crewmember suffering from ‘the bends’ following a spacewalk. If we developed a serious illness, like appendicitis for example, the situation would be assessed by our doctors on the ground whether it would be better to stay on board and use medication, or to return to Earth (appendix removal is not standard procedure for astronauts prior to flight).

19) What would happen if there was a fire on the Station?

We’ve already had a couple of emergency fire warnings since I have been on board but thankfully both turned out to be false alarms. However, we treat every situation as a real emergency of course. Fires can vary between open fires (visible flame), smoke, smell of burning, or just a smoke detector alarm but no other indications. We have procedures that deal with each case depending on the severity of the situation. In the most serious cases, we would don breathing apparatus and fight the fire using either carbon dioxide, water mist or foam fire extinguishers. We would also try and locate the power source and remove electrical power (electricity is most likely to be the cause of a fire on board). The smoke detectors trigger an automatic response from the ISS to shut down all ventilation systems, so as not to feed oxygen to the fire and to reduce the spread of smoke throughout the station. We have special detectors that tell us if the air is contaminated with carbon monoxide and other harmful gases – these are used to know when it is safe to remove our breathing masks. We also have special filters and equipment on board to clean and scrub the atmosphere to return the ISS back to full health. Only as a last resort would we evacuate the ISS in our Soyuz spacecraft. Interestingly, the Soyuz does not have any fire extinguishers. The way to fight a fire in the Soyuz is to close your helmet and depressurise the whole spacecraft… no oxygen = no fire!

New answers 6 June 2016

20) With the Space Station moving so fast, do you ever feel motion sickness?

We do move quickly across Earth’s surface (ten times the speed of a bullet… that’s pretty quick!) but this visual effect does not cause any motion sickness. Of course, it takes a short while to adjust to microgravity and during the first couple of days in space you might feel some ‘space sickness’. This is different to motion sickness though. We normally associate motion sickness with long periods of feeling unwell and it can be quite debilitating. Space sickness on the other hand can come and go quite quickly, even catching you by surprise, and its possible to function normally in between short periods of feeling unwell. Once our body learns to ‘accept’ this conflict between vestibular and visual information, we can do things in space which would make you feel very sick on Earth. For example, I have tried spinning in space for several minutes at a rapid speed whilst moving my head up and down with my eyes open. This kind of stimulation on the Earth would be very provocative – but in space it’s no big deal. I can sometimes make myself feel dizzy, but there is no associated nausea. During my spacewalk there was one point when I was returning with the failed ‘SSU’ that Tim Kopra and I had replaced. I had to descend along a spur that connects the main truss to the airlock. Half way along this spur I looked down at Australia beneath me and felt a sudden feeling of vertigo. It made me smile because I had been ‘out the door’ for well over an hour by that stage and it caught me by surprise. NASA astronaut Chris Cassidy had told me that, if that ever happens, wiggle your toes and it will make you relax your grip… it worked!

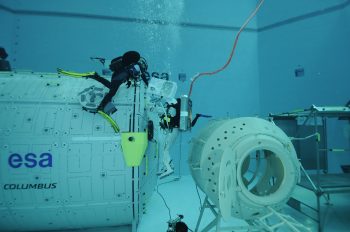

21) In scuba diving, there is a syndrome known as ‘fear of surfacing’, where divers don’t want to come up. Did you ever feel like this on your spacewalk?

I’ve also enjoyed some spectacular dives where the temptation to go deeper and stay longer is strong. As for coming in at the end though – I think the circumstances of our spacewalk made it very clear it was time to come in. After all, you can clear your mask easily under water – it’s a bit harder to clear a helmet filling with water in space! Also, our spacewalks are choreographed to the minute and we have a huge support team in Mission Control looking after us and checking our every move, so there’s always someone ready to remind us of when it’s time to come back in, no matter how tempting it may be to stay outside.

22) Can you see aircraft or ships from space?

It’s not easy to see small objects with the naked eye – often you can pick out a ship’s wake or aircraft contrails and follow it back – but with zoom lenses (as you might have seen from https://flic.kr/p/FfSp2Z), we can see large ships.

23) In the photos of the aurora, is this how they appear to the naked eye or are the colours more visible because of the camera exposure?

For the aurora photos, they are pretty close in terms of colour and intensity – but if anything we see a more spectacular image with the naked eye. The camera doesn’t do justice to the eerie way the aurora snakes, ripples and changes intensity – although some of the timelapse sequences have captured this.

24) You’ve trained for most situations on the ISS, but what thing surprised you most when you first got into space?

The thing that most surprised me was how black space appears during the day. You know that stars are out there, but because your eyes adjust for brighter objects, space looks so incredibly dark. During my spacewalk, it felt almost intimidating being on the farthest edge of the Space Station and having nothing but the vast blackness of space over my right shoulder. That was a good incentive not to let go!

25) What feature or place on Earth’s surface do you look forward most to seeing on each pass?

Well, on viewing Earth’s surface, it’s all truly amazing. Often I go to the window expecting to see a certain mountain range, city or other landmark but I’ll come away with photographs of something completely different. Earth has so many secrets and the longer you spend in space the more time you have to find and appreciate them. Even every sunrise and sunset is unique and special in its own way.

26) Do you dream differently in space, or dream of anything in particular?

Not particularly. I think I sleep more lightly in space and don’t dream that often – when I do I have been on Earth.

27) What’s your favourite part of your day in space? I enjoy wrapping up at the end of the day and having some time to take photographs, look out the window and call friends and family. The working day is fun but we’re always trying to keep to a tight timeline, so it’s nice to have a couple of free hours in the evening.

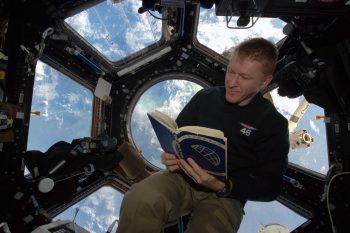

28) Do you have any personal reading material, and what would be your choice of book to read in space?

It’s here, I have an original edition of Yuri Gagarin’s autobiography Road to the Stars, https://flic.kr/p/FMzfc9. This is Helen Sharman’s personal copy, signed by her crew and Gagarin himself. I can’t think of a better choice, and it’s an honour to borrow this book and read it up here.

29) How do you tweet and Facebook from space?

Both great questions. I’m tweeting and posting from a regular laptop inside my crew quarters. Our signal is relayed via satellite to a desktop PC at Mission Control in Houston that mirrors what we do on our screens up here (for security purposes, there’s no direct internet connection). It’s much slower than your average wifi (think dial up speed!) and only available at certain times during the day, depending on satellite coverage. However, the fact that we get internet at all in space is quite remarkable and it’s OK for basic access to social media and for reading news websites – but it doesn’t provide the bandwidth for video streaming. So yes – I do see your comments, and although I’m not always able to reply to all, I do appreciate them very much!

30) What camera do I use?

All my Earth pics have been with a Nikon D4 and one of these lenses.

31) What kind of watch do I use?|

All ESA astronauts are issued with the Omega Speedmaster X33 Skywalker, more info in this ESA article.

32) Can we see other planets from space?

Yes, we can see other planets from space and I have been able to photograph Venus rising over Earth and also Jupiter, Mars and Saturn. Most of our windows look down on Earth – so although we see the planets rising and setting it’s much harder to see them when they’re above us. Here’s Venus rising just before the Sun

https://flic.kr/p/GXKsxZ

33) What’s it like to sleep in space, and where do I sleep?

I sleep in my crew quarter, which is a bit smaller than a public telephone box, but big enough for everything I need. We try to get about 8 hours of sleep per night, but this varies and we can go to bed anytime from 10 p.m. to midnight (we’re on GMT). I strap my sleeping bag loosely to the wall and then zip myself into it and let myself float. Our sleeping bags are quite close fitting, which is good because you don’t want to move around inside them too much. I find it easy to sleep in space but it’s probably not as good quality sleep as I get on Earth. It’s sometimes hard to get your arms into a comfortable position – I normally just fold them across my chest. I am actually looking forward to sleeping in a proper bed again and having the feeling of gravity pull me down into a comfy mattress!

34) What’s my favourite space food?

I love making myself a peanut butter and jam sandwich in the afternoon. We don’t have proper bread so I use a tortilla wrap instead, but it tastes pretty good! My favourite foods are the breakfast menus (scrambled eggs, baked beans and sausages!). Also, occasionally we have ‘Maple Muffin Pancackes’ which taste great for breakfast – especially with a bit of extra honey on them! And, of course, I have my favourite ‘Space Dinners’ salmon dish from the kids competition and designed by Heston Blumenthal.

35) When do you come home? What happens after you’ve landed?

We undock and return home on 18 June. Undocking will be 05:46 GMT and we’ll land around 09:15 GMT in Kazakhstan.

36) How fast is your reentry, and what does it feel like?

Well, I’ve only done simulations so I can’t tell you from experience (yet!) After undocking, the Soyuz has to move away from the Station at a careful 0.1 m/s. Then there’s a 15-second separation burn of our engine when the Soyuz is about 20 m from the Station. When we’re about 12 km from the Station, our main engine fires for 4 minutes 38 seconds to slow us down. This reduces our orbital speed of 28800 km/h and sets us on course to enter Earth’s atmosphere (after this deorbit burn we’re coming back to Earth whether we like it or not!)

Once we’ve completed this burn, we no longer need the Service Module and Orbital Module, so pyrotechnic bolts fire and they separate and burn up on reentry. Our Descent Module will be tumbling slowly as it enters Earth’s atmosphere at about 120 km altitude. This is where we get the greatest heating effect and our speed is dramatically reduced.

Aerodynamics start to take effect and the capsule orients itself to enter the atmosphere, heatshield first. We’ll be pushed back into our seats with a force of 4–5g for several minutes whilst the heatshield protects us from temperatures of up to 1600 degrees Celsius. This means we feel four to five times our own body weight and during this time the plasma around our spacecraft will prevent us from communications with mission control and the ground search and rescue team.

Next we will feel the jolts of our drogue and main parachutes deploying. These slow us down further, the drogue from over 800 km/h to 250 km/h, and the main to 25 km/h. This is a very dynamic event – the capsule will be rotating quite violently beneath the drogue chute as it slows us down rapidly. Once the main parachute opens we’ll have about 15 mins until landing. During this time we’ll establish communications with the search and rescue team and prepare the spacecraft for impact.

At the last moment before touchdown, ‘soft-landing thrusters’ fire to limit the landing speed to around 5 km/h. We sit in custom-fitted seats that absorb some of the shock of impact – but something that all astronauts agree on is there is no such thing as a ‘soft landing’ in a Soyuz. We’re advised to tighten straps as much as possible, push your neck firmly back into your seat, brace arms and knees together tightly and make sure your tongue is not between your teeth! Finally comes the hatch opening and the first fresh scents of Earth since leaving the planet in December.

37) What happens after you’ve landed?

After leaving the Soyuz, we’ll fly by helicopter to Kostenay, from where Yuri will continue to Star City near Moscow and Tim and I board a NASA aircraft to Bodo, Norway. As the aircraft refuels, I’ll say goodbye to Tim and transfer to another plane to Cologne in Germany. I’ll arrive at the European Astronaut Centre (EAC) in the early hours the next day. This is the home base of all ESA astronauts.

Here, ESA’s medical team will supervise my rehabilitation after spending over six months living in weightlessness. In addition to rehab, I’ll have many medical checks related to the human physiological science studies that I’m participating in and debriefs on various aspects of my mission.

The first couple of days on Earth will probably be quite tough as my bones and muscles adjust to coping with gravity once again. In addition, my balance will be a bit messed up since my brain has sort of switched off the signals coming from my vestibular system, as these are not required in space and only contribute to space sickness. However, on Earth that shifting fluid in our inner ear is vital for helping the brain to detect the gravity vector and to maintain our balance accordingly.

Also, I’ll take some salt tablets and try and load up on fluids during the final few days in space, since my body spent the first month or so getting rid of the excess body fluid that is not required in space but I’ll need that back again on Earth. Lack of body fluid, low blood pressure and a weak cardiovascular system can contribute to ‘orthostatic intolerance’ (aka fainting) or lightheadedness when standing up too quickly.

New answer 25 October

Who has been your hero or inspired you in your career?

For me, one of the most inspiring figures has been NASA astronaut Bruce McCandless, the first astronaut ever to do an untethered spacewalk. Just because what he did was really groundbreaking: a very high-risk activity and the level of isolation he must have felt hundreds of metres from the Space Shuttle. Just him and a jetpack, no cables, no tethers. It takes a lot of guts to do that. Plus he was selected back in the 1960s as one of the original Apollo astronauts but he had to wait 18 years to make his first flight. Eventually, he logged over 312 hours in space, including four hours of EVA jetpack flight time. Just shows if you stay focused on your dreams what you can achieve.

Discussion: 69 comments

Hi Tim

Thank you for all your posts and beautiful photographs.

What do you miss most (apart from you family and friends of course) while you are on the ISA that you can’t have up there?

And also is there anything that you have experienced up there that has surprised you?

Sue

Fantastic article!

What ‘atmosphere’ do you breathe and what pressure is applied? Are they the same as those at ground level on Earth or modified?

First.

Thank you so much for all this information it really helps give some understanding of what your life is like on board the ISS. I am fascinated with every aspect of it so please keep all the fantastic photos and info coming. You are doing a phenomenal job which will impact/improve, perhaps not my life but that of my two grandsons so thank you for that. Much love and all good wishes for a continued successful and enjoyable mission.

If the fluids in your body are drawn towards the center, how does that affect your balance? Obviously balance isn’t a problem in space generally, but are there any situations where it might be?

Thank you so much Tim. We have loved reading this.

How much does each supply ship cost? (Is it a very costly way of emptying the rubbish bin?)

Amelia age 9 Evangeline age 6

Wow, thank you so much. So interesting. Hope your having a wonderful Easter x

Thanks for the information, Tim. It’s a fascinating insight to life aboard th ISS.

Thanks for this fascinating look at your lives inside the ISS. I think of you all every time I watch the ISS pass overhead. I have a band and even if we are playing to a large group outside, I will stop the song and direct everyone’s’ attention to the ISS. Beautiful. Thanks for being who you are. If you had a chance to reply at all, I would be absolutely thrilled.

Dennis Gossman

I’m finding all your photos and updates so interesting and I really appreciate the time you take to share your experiences with us. I’ve never really been interested in space before you went up and often struggled with science and maths at school (I’m a linguist) and I’m so surprised that I’m now “gobbling up”‘ all the information you’re sending and doing lots of reading/study on my own and am absolutely loving it so thank you so much for inspiring me!! Stay safe up there. Sarah x

These up dates and your accounts are wonderful, I was one of those that stayed up for the first moon landing and now to have communication is just amazing, thank you so much for sharing your experiences .

Brilliant Tim, just seen Hestons programme about new space prepared food.

I love seeing your photographs and posts. I know I come across as a weird stalker kinda person. I work with different groups with health problems (running art sessions). One art group I am working with are elderly people in a care home in Dorset. They are doing a project that connects them to the big wide world outside of their care home… They wrote messages and had pictures taken with these messages. These have been placed on social media (www.facebook.com/connectionsprojectcullifordhouse). The idea of the project is to raise awareness of old age problems: loneliness, dementia, macular degeneration etc etc… I really want everyone in the universe to say Hello back to them. Just by taking a selfie with a note (like the replies on my project page) it takes a few minutes, it’s free and would help raise awareness. I don’t make any money from the project. I work with these groups because I care and I am passionate about Art as a means of communication. I have tagged you and Jeff (on the ISS) in loads of posts on Instagram and Twitter… sorry.. I am not a stalker…. Just a passionate artist. (Instagram @bongley)

Thanks Maj Tim for making us all so proud. Much appreciated information. We often see the ISS fly over Auckland New Zealand on a clear summer night. We often raise a glass of red for you as you fly over! Give us a wave some time and please wish all the crew a happy Easter in space. Trev Kate and family in NZ

A great read! Thanks for all the info. I look forward to following your posts.

Thank You Tim for taking the time to compile this. So interesting and informative, really enjoyed reading it all.

Thank you, for this and all the other information that you have shared with us

Hi tim

A little question, when did you earn your bachelor of science ? Before or after your helicopter pilot training ?

Thx and Fly safe

Tim, how much of a delay is there between communication between yourselfs and earth when in contact and does it differ with audio/visual? Keep up the amazing work. Love all the pics on Facebook. X

Thank you so much – answers to all my questions including some I hadn’t even thought of! We were lucky enough to be at NASA in Houston just after Christmas and it really ‘peaked’ our interest in your mission! Very good luck to you for the rest of your trip!

if there is a fire on the ISS, how do you use a fire extinguisher. if you did it as you would on Earth, would you just be propelled backwards?

Thank you for all your information, it is all so interesting and informative. I echo Paula’s comment above. I have been absolutely fascinated by all your photos and updates. Please keep them coming.

Regarding the Soyuz Spacecraft mentioned in the last comment. I presume (hope) that once you are in your space suits and you have depressurised the spacecraft, that you would have enough oxygen in the space suit to then get back to earth?!?

These answers are so useful. I am a deputy headteacher at a Primary School in Leeds and we are all following your tweets avidly. This post is great! Good luck for the remainder of your stay up there!

Hi Tim,

I think what you are doing is so inspirational and the way you are engaging young children in your mission is wonderful. You have managed to excite so many of us about the wonders of space travel and I really admire how you are going about doing so.

I am a literary agent at the biggest talent agency in Europe and I know that you are writing a foreword for a children’s book but I have no doubt that publishers would be very keen indeed to work with you on your own book, be it for children or adults.

I would love to speak to you about this. If you are interested do please email me at the address below.

I have no doubt that you could create an exceptional book that would educate us all even further about this remarkable journey you are on.

Best wishes,

Ariella Feiner

Hi Tim, my name is Lilly and I’m age 7.

I was wondering what games you play in space when you get bored.

Tim peak compared to Earth do all the stars and planets look any bigger????? I no that you eat food in a choob but How do you get the food out of the choob?????

What does weightlessness feel like?????? Where do you sleep??????love Isla age 6

What precautions do you take regarding static electricity build up? I imagine you all touch metal work frequently but when you don’t and then bump into someone is it an “ouch” moment rather than “oi”. I assume static electricity is much more of a problem in space than on Earth?

Tim peak ho else is up there with you?

Are you ok up there what do you do up in spac only what I no that you eat and do exsaz is that all what you do or

moro. We’re is the

spacecraft ?????!!!!!

I love you Tim peak and I am a dog so Isla helpt me

Does the stars and plants look biger

Its truly amazing the work you are doing, the pictures, videos and insight you are sharing with us is awesome – thank you so much.

I no I have done a lot of comet”s it’s because I have so much questions ?How cold is spac and is it warm are cold because my topic is spac and were Leung all about you?

Hi Tim please could you tell me if you went outside into space with wet hair (just imagining you could breathe and didn’t need a suit) would your hair dry? Do you need oxygen or wind to dry it? Thank you. Eliza (12yrs)

Hello Tim, your photos and posts never seem to be short of amazing! One wee question if I may, ” Do you ever see jet contrails from commercial airliners below on earth from the station?”

Hi Tim

Kacie and Patrick here we won’t go know what’s it like with a surtent amount of oxygen ?how do you entertains your self in space ?how do you keep clean ?how do you eat in space or what do you eat in space?

MAYBE you read the article before asking

Hi Tim

We are both from Stoneydeph Primary School and we have been learning about space and are very fascinatied about it. We have a question each for you;

What got you interested in space?

Were you scared in and out of the rocket and if so, why?

The first question was Lenny’s and the second was Bethany’s.

Tim.hope you are well up there.I understand because of being up in space,your body because weaker and deteriates quicker than on earth obviously this is why you exercise.

Can you actually feel a difference in your body,in yourself since being up there. Do you sexuall urges change

How can I find out when you are passing over where I live ( Hayling Island ). Is there a time table I could look up ?

Try here: https://iss.astroviewer.net/

hi Tim, in micro-gravity what would happen if you had a sneezing fit ?

How do you calculate your mass?

Can you detect big earthquakes up there? Is there a visual effect noticeable of the earthquake’s energy such as a vibration or a ripple in the athmosphere or maybe something else?

What is the first thing you’re looking forward to eat when you’re home?

Most importantly Tim, at what point will you be re-united with your family??

Tim, I have enjoyed looking at your photos of Earth from space. I wonder if there is anywhere on earth which you would now like to visit, having seen it from space, which you wouldn’t have considered visiting before?

Hi Tim

Do you wake up or down?

A good web site is iss.astroviewer.net

To heck what days is close to the UK is clickon observations

Hi Tim, thanks for all your information throughout your time on the ISS 🙂 One question I don’t thing anyone has asked? Seems a silly question really, but is there a temperature outside of the space station? I would imagine it would be horrendously cold, but would love your input on this. Many thanks

Ive watched, listened,read, played spacerocks, and can honestley say its been a fabulous experience sharing this trip through your blog pictures and tweets . I will be glued to Nasa tv to watch your journey back to Earth . Safe journey home and Thank you for many hours of “something completely its been different “

When you open the airlock to go into space on a spacewalk I assume you loose a bit of the air and oxygen from the ISS. How is this replenished? Is there any way of ‘making’ oxygen or is it all bought up on supply ships? Also, is the air in the ISS mixed so that is the same composition of gasses on earth or is it more oxygen rich – I guess not as this would more a fire risk I suppose?

We’ve been told you can see penguin poo from space. Is it true?

Hi Tim

I can’t express my gratitude enough for how much you have inspired and captivated my children aged 4 and 7 yrs with your journey.

They have asked so many questions about space and the stars but they both have a question they’d like to ask. They would love to know if you could fly a kite in space?

Safe journey home and thanks again for making us feel like we have been with you on the space station!

Susan

We’ve asked this question already on twitter, but how does silence sound on space? is it “quieter” than on earth?

Tim Peake hope you are enjoying your last few days in space. I’ve posted a few times to let you only that Portishead Primary school in Somerset have entered a float into the carnival in your honour. Our theme is Ground Control to Major Tim and it tells the story of your time in space. Our carnival preparations for your return are coming together nicely and the kids look forward to honouring you on the 18th. Would be fabulous if you could send back a message for us to show to the children. Many thanks

Tim Peake hope you are enjoying your last few days in space. I’ve posted a few times to let you know that Portishead Primary school in Somerset have entered a float into the carnival in your honour. Our theme is Ground Control to Major Tim and it tells the story of your time in space. Our carnival preparations for your return are coming together nicely and the kids look forward to honouring you on the 18th. Would be fabulous if you could send back a message for us to show to the children. Many thanks

Hello Tim, my name is Jack it is my 3rd birthday and I am having a astronaut Tim party!!

Thank you so much Tim. My son Jack gets so excited when he sees you in space and is your biggest fan. You have inspired a whole generation as well as my son’s Jack and Luke. We would like to invite you to Jack’s ‘Tim’ party but I understand if it is a bit far for you to travel. Jack is very concerned that he has your rocket and you won’t be able to get home without it – can we send it to you?

Wishing you a safe return

Tim will you be watching the Wales and England football match on Thursday?

It’s six months+ of significant experience which has positively impacted on most of us, and will continue to do so. I’m struck questioning what little I have achieved in those six months! With your unique perspective and experience what would be your top tips for average Joe who won’t be entering space, but would still like to make an effort their approach to life is worthwhile?

Occasionally the Russians will use another rocket to boost the ISS height above earth, when this kicks in do you get any sense of an artificial gravity or not?

Also – is there a common orientation that people work to being “the right way up” through the ISS?

Hi I really want to know who helped you to get into space ? My class is learning about you this week and I need this ripely as soon as possible

i am Cheyenne in 4th grade at Mildred helms and i am in gifted and i need to find out what a science officers do in space because we are studying about space and jobs in space.Answer this please and thank you.

Can you see Salisbury Cathedral from space?

When you did your EVA training was it done at the ESA-NBF in Cologne or the NASA-NBL in Houston (or may be both) ?

About what dates/periods of time were you specifically focused on EVA training each each location ?

Hello

Hello Tim Peake, We are Penguin Class(Y1) at Fishbourne Primary School and we are going to be making our own rockets. We have had a visit from a man who makes satellites and he told us all about rockets and you too. We have some questions for you. 1. How long does it take from blast off to get to space? 2. Do plants grow in space? 3. Can you play games in space? 4. How do you wash in space? 5. How do you walk after being in space?

Why did you want to become a Astronaut ? what made you wonder about the universe? and what was it like, I bet it was enrapturing and absolutely breath taking.

_ p.s this is for a school assessment

How do you feel when you are back on earth, how does the gravity impact you?