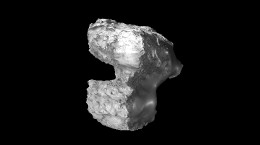

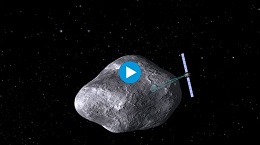

Today’s CometWatch post delves back in time to October last year, when Rosetta was orbiting the comet at a distance of just 10 km.

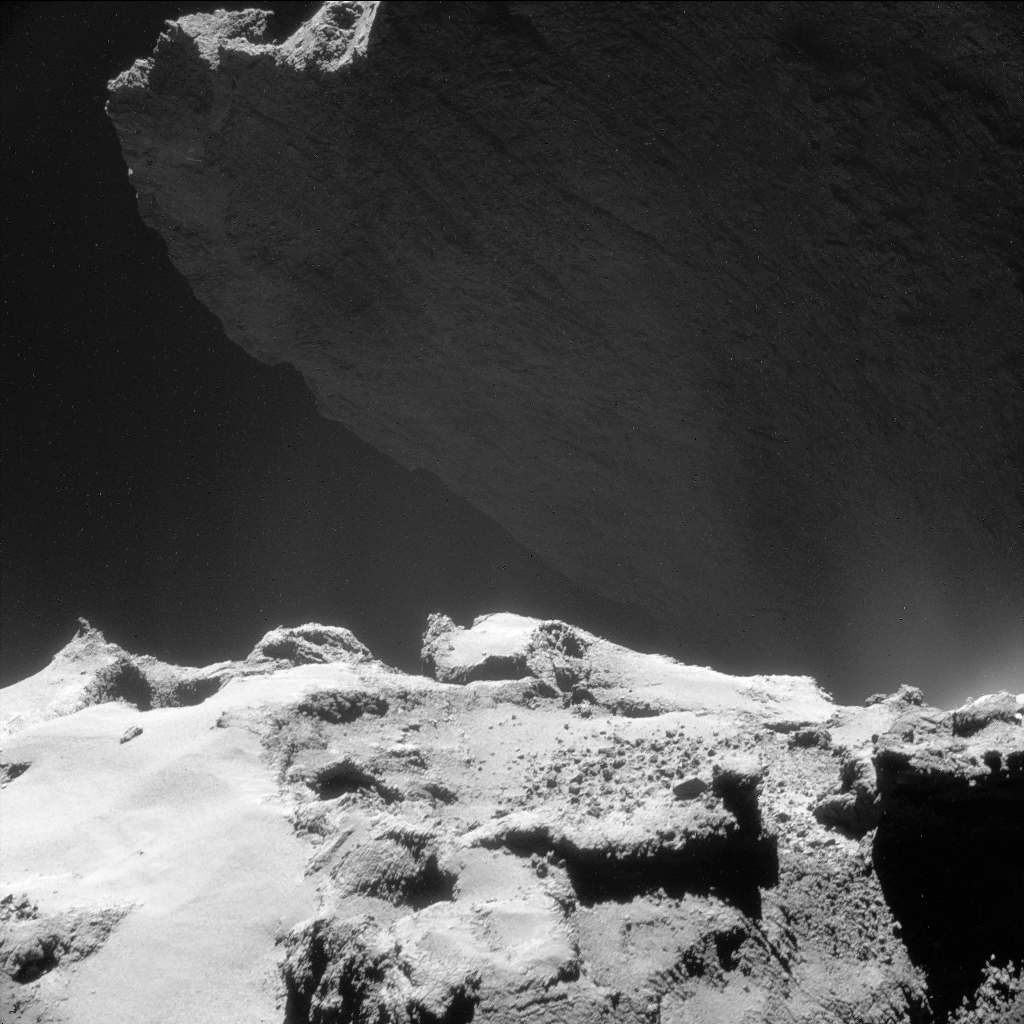

Single frame, processed NAVCAM image of Comet 67P/C-G taken on 23 October from a distance of 9.8 km to the comet centre. Credits: ESA/Rosetta/NAVCAM – CC BY-SA IGO 3.0

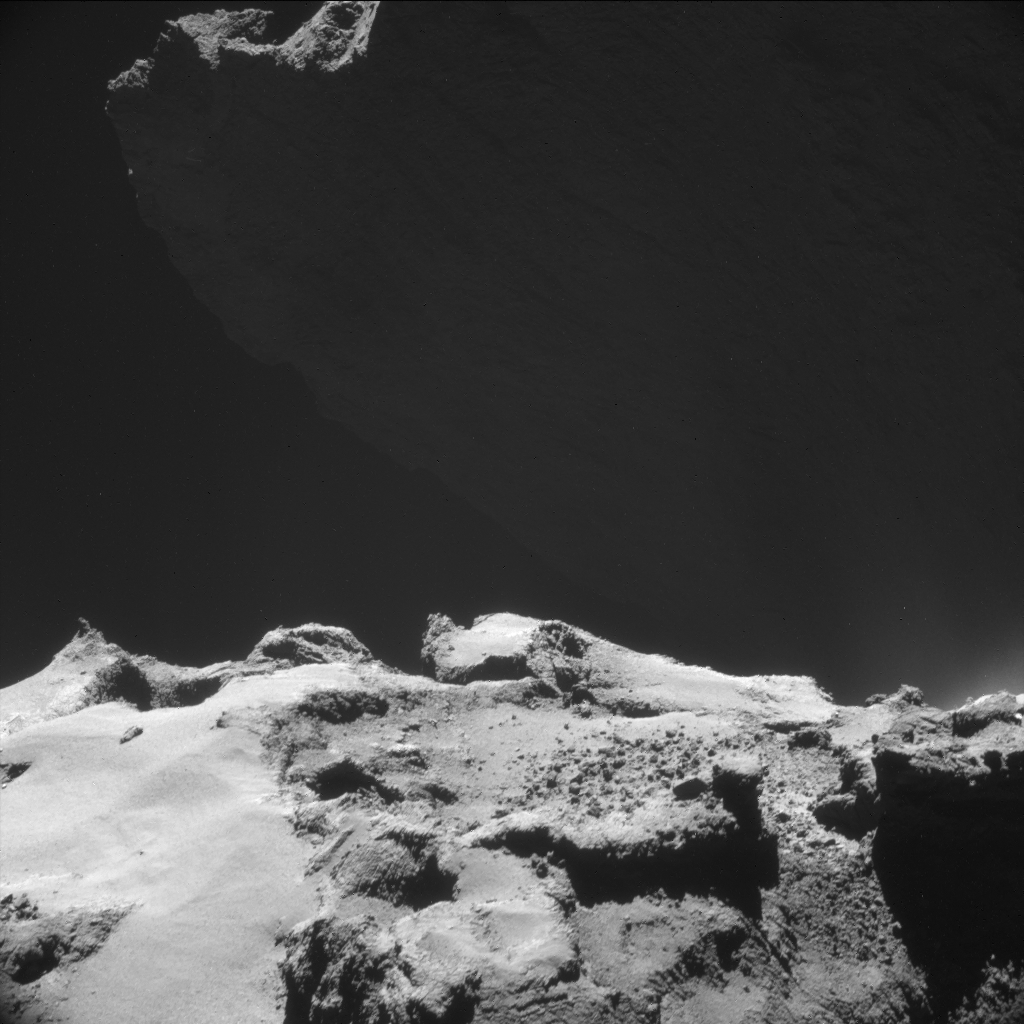

This single frame NAVCAM image was captured on 23 October, when the distance to the centre of the comet was 9.76 km. The average image scale is therefore about 83 cm/pixel and the image measures 850 m across (note that because of the viewing geometry, foreground regions are up to 2 km closer to the viewer, and therefore have an approximate scale of 67 cm/pixel). For reference, an image in a similar orientation was captured on 26 November.

The scene highlights the hauntingly beautiful backlit cliffs of Hathor, the summit just catching the sunlight at top left. The image has been lightly processed to better bring out the details of this region, and also reveals the diffuse glow of the comet’s activity. Indeed, subtly brighter patches can be traced against the darker background, in particular at the right of the frame at the transition from the foreground terrain to Hathor in the background.

If you were standing at the base of Hathor in the Hapi region – out of view in this image – these near-vertical cliffs would tower some 900m above you. As can be seen here, Hathor is characterised by sets of linear features that extend for much of the height of the cliff. In places, lineaments and terraces also cut across roughly perpendicular to them. As described by Thomas et al in an OSIRIS science paper earlier this year, Hathor may be an eroded surface and as such is showing us the internal structure of the comet’s head.

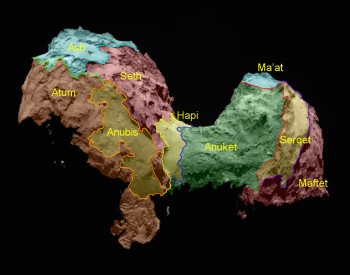

In the foreground, contrasting terrains within the Seth region on the comet’s large lobe are observed. While the left-hand portion exhibits a smooth surface, the right-hand portion shows outcrops of more rugged terrain and numerous boulders. The exposed surfaces also display linear structures in various orientations.

In the foreground, contrasting terrains within the Seth region on the comet’s large lobe are observed. While the left-hand portion exhibits a smooth surface, the right-hand portion shows outcrops of more rugged terrain and numerous boulders. The exposed surfaces also display linear structures in various orientations.

The portion of Seth seen here is at an intersection of several regions: at the far right of the frame lies the boundary between Seth and Anubis, while just out of view beyond the bottom of the frame are Ash and Atum.

Today’s image is one of many that will be included in the NAVCAM data release scheduled for the end of this month. This will see the release of the entire collection of images taken from the 10 km orbit last year, along with images taken around the events of comet landing. You can browse all NAVCAM images released so far in the Archive Image Browser.

The original 1024 x 1024 pixel image is provided below:

Discussion: 18 comments

Again, when will these releases include images taken with OSIRIS and not only the NAVCAM.

How many OSIRIS images have been taken up to now and how many have been released ?

“Imagine a little world where half of the sky is like rock”.

As a child, would never.

Would there happen to be an estimate of how likely it is that 67P will split in two before the end of the mission? Would the pieces fly apart or collapse together?

Very spectacular image! Thanks. The next few months will be very exciting as we go through perihelion.

Lovely view of the jets from Seth to Hathor.Would dust grains from Hathor necessarily fall down to Hapi even though the gravity is pretty weak? The 26 November picture has a hint of individual grains flying out as though some of the jet was reflected off Hathor. This raises an interesting question: why are there no jets from Hathor, which should be visible when seen from a suitable angle? The smaller lobe does have jets, but not here.

Thanks, Emily, for the earth based observatory pictures of 67P. I should have realized the comet was behind the sun…

Wow, now this is really impressive. Can’t wait for OSIRIS image. Keep going guys

If well seismic waves by impacting dictates vectors to some layers, part of that energy is ‘channelized’, diffracted by the semi-crystalline structure of core’s material.

The ‘music of the spheres’ ends as a far and vast ‘reverberation of the crystals’.

That brings the plausibility of fractures and gaps at the crystal level, too.

This is cometary fiction.

It is too bad this probe doesn’t have a 3D camera. Some of these images would be much better viewed with depth.

Sometimes two consecutive images can be used to create a 3D stereo image.

Ok, by now I’ve found a pair of NavCam 2×2 rasters usable for a 3D stereo, see the other thread, as soon as it’s approved:

https://blogs.esa.int/rosetta/2015/05/28/navcam-image-bonanza-close-orbits-and-comet-landing/#comment-462966

Is the Rosetta navigation camera monochrome, or is the scene really that colorless?

Both, the camera is black-white, and the comet is dark grey (actually almost black) with only small variations in color.

It would be slightly reddish under white light. But in the sightly greenish sunlight (due to the lacking atmospheric filter of Earth) the comet looks like with a small cast to greenish. But that’s barely perceivable without saturation enhancement of the images.

Actually the bright neck regions have a tiny cast towards bluish, relative to the darker areas.

On Robin’s ‘haze’ would precise that it’s more like ‘smoggy haze’. Also that is more evident at terminator line.

Also that is more evident around clean, core semi-crystalline material.

Thanks goodness for each and all glimpses you share of that mysterious dancer you’re dancing along with, Rosetta.

NAVCAM & Flight Operations (yeah, you know what I mean) deserve to be acclaimed as the most scientifically dramatic & romantic teams ever to SHOW TRUE SIGHTS OF AN ALIEN THING, BILLIONS YEARS OLD, IN SPACE!

Can anyone say if the very small objects in the foreground are the size of a car, house, person, etc.? These are the ones that look a bit like grains of sand.

That’s maybe not quite up-to-date anymore, but GIADA measured grains between 0.03 and 2.5 mm:

“The GIADA team find that the dust particles impacting on their detectors can be separated into two families: ‘compact’ particles with sizes in the range 0.03–1 mm, and somewhat larger ‘fluffy aggregates’ with sizes between 0.2 and 2.5 mm.”

https://blogs.esa.int/rosetta/2015/04/09/giada-investigates-comets-fluffy-dust-grains/

Occasionally grains up to the meter scale may be ejected, maybe during explosive eruptions. Those large grains seem to be in more distant bound orbits.

So, your size of “grains of sand” should be about right in many cases.