ESA’s current astronaut-in-residence arrived at the International Space Station on 12 November in a Crew Dragon spacecraft for his six-month Cosmic Kiss mission.

Matthias, who is the 600th human to fly to space, is now well-adjusted to his ‘space legs’.

During November, he handled the Station’s 17-m-long robotic arm, Canadarm2, to release the Cygnus spacecraft and prepared to do so again on 2 December to assist spacewalkers from inside the Space Station. Piloting the arm requires mental gymnastics to understand the motion in weightlessness.

Space life also requires quality sleep. Matthias had his bed set-up by fellow ESA space traveller Thomas Pesquet, who made sure ventilation and noise levels were pleasant in Europe’s Columbus laboratory for him.

This new place for Matthias to sleep and relax is called CASA, short for Crew Alternate Sleep Accommodation, and the astronaut has already made himself at home.

Another quiet place in the space quarters is new module on the block, Prichal. The latest Russian node adds up to six more docking ports to the Station. And, because it has no active components, it is nice and calm inside.

A new space scientist

Matthias is supporting a wide range of European and international science experiments and technological research on the Station.

Like on the ground, microbial contamination is a concern in space. The Touching Surfaces experiment exposes a series of five panels, made of different materials, to the indoor environment of the Space Station. Matthias and his fellow astronauts are encouraged to touch these panels frequently before they are returned to Earth for analysis. Scientists will then look at how microorganisms stick to these panels, and for how long. Results could aid development of novel antimicrobial surfaces for the health care sector and food industry.

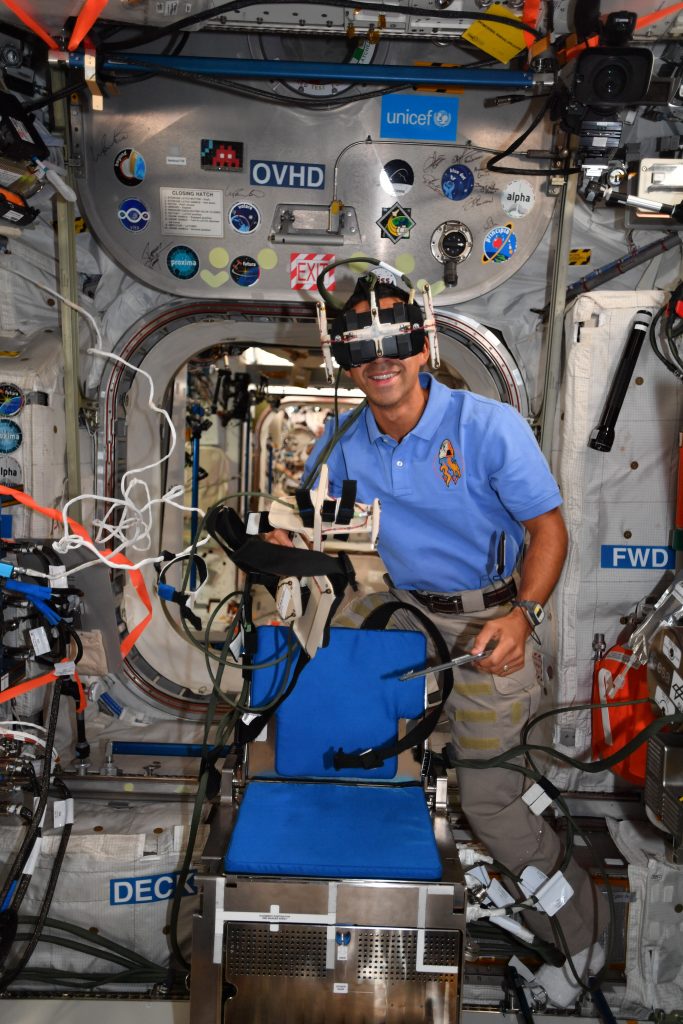

Matthias’s body was also the subject of several science studies. While a thermal sensor strapped to his forehead monitored his core temperature and circadian rhythm for the Thermo-Mini experiment, the Retinal Diagnostics study captured images of his eyes to detect any vision pathologies common amongst astronauts.

Matthias wore a breathing mask and two devices on his chest filled with sensors during a static bike ride. The wireless devices monitored his heart rate, oxygen and carbon dioxide levels for the Metabolic Space experiment, a technology demonstration to improve cardiopulmonary diagnostics and assess performance in space without restricting mobility.

Old friends

A familiar experiment on the Station that monitors muscle tone and stiffness during spaceflight, Myotones, joined forces with a new study to improve exercise outcomes. The EasyMotion experiment uses a wearable electro muscle stimulation (EMS) suit that activates the musculature and has the potential to optimise Matthias’s fitness routine in space. The combined inputs before, during and after flight of this research aim to understand the physiological strain for astronauts and could lead to new rehabilitation treatments on Earth.

NASA crewmates Raja Chari and Kayla Barron also ran their first sessions with Grip and Grasp. These neuroscience experiments investigate how our brain takes microgravity into account when grabbing or manipulating an object. The studies help identify the workings of the vestibular system that helps us maintain balance.

One of the side effects of a long stay in space is the loss of bone density and muscle mass, so flight surgeons want to keep an eye on Matthias’s body changes.

Even before enjoying his Thanksgiving dinner in space, Matthias began logging his meals to track his energy intake.

While the NutrISS experiment assessed his nutrition, he jumped on a peculiar space scale to measure his mass in zero-g.

Measurement of mass in zero gravity requires other techniques than on the ground – a normal scale wouldn’t work here. This Russian hardware uses the resonant frequency change to calculate my mass,” he explained.

Radiation is another well-known space hazard. Matthias dotted 21 Dosis 3D radiometers around the Station to get an overview of where radiation is most prominent. He placed 10 pouches inside the Columbus lab, and scattered a few others in other locations to build a three-dimensional map of the radiation environment.

On the topic of space radiation, the Lumina experiment is also underway and will run kms of fibre optic cables throughout the Station to see if they are a viable technology for monitoring ionising radiation in real-time. This technology would be useful in settings with limited habitable modules and power, like on a spaceflight to Mars.

But for now, we wish Matthias another productive month of science and operations in low-Earth orbit.