Before I realised it, the cave clamped down on me. A completely different world surrounded me, absorbing all my attention. This was not a simulation, but real exploration in a hostile environment dominated by darkness.

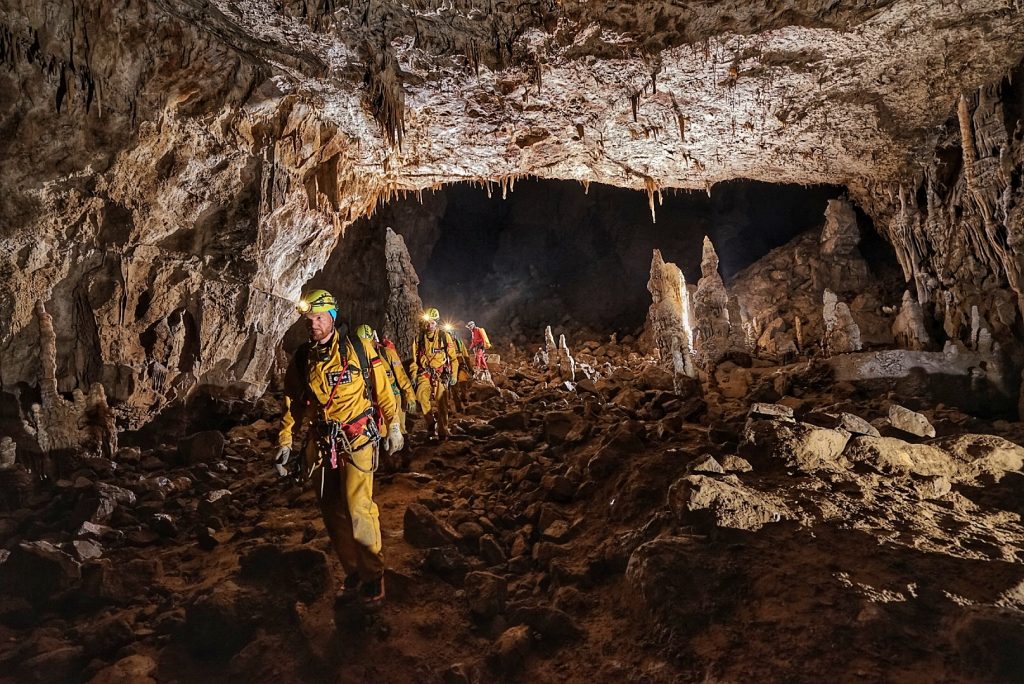

Darkness was my steady companion during the six days of underground life with ESA’s CAVES training course. Don’t be deceived by the spectacular images of the underworld. Professional photographers meticulously lit up the caverns to show them in all their glory. In reality, we could barely see what waited for us a few metres ahead, outside the reach of our head lamps.

The limitations in what I could see heightened my other senses – with the exception of smells, which were dampened by the moist air. A constant temperature of six degrees Celsius and 100% humidity in the air made me feel cold and wet most of the time. After crossing some water passages, nothing seemed to get dry ever again.

The sense of danger was also vivid. The unknown was around each corner, including big drops and slippery cliffs. The entrance to this particular cave in Slovenia required us to rappel a 200-metre vertical shaft. It was during this long descent that I felt transported to another world.

That initial drop set the divide between the old and the new world ahead of me. It quickly made me feel remote and isolated. But nevertheless, knowing that getting out was not an easy option did not stress me. On the contrary, it helped me focus on the next steps.

Space analogies

When you ignore some details, it is amazing how similar cave exploration is to going to space. After my experience with CAVES, I can say that, so far, this is the best analogue that I know for astronauts to mentally prepare for space.

Consider time. Like on the International Space Station, we were governed by a tight schedule and strict planning. With no reference of day and night below Earth’s surface, we lived by the watch.

Scientific experiments were often the drivers of our exploration. We carried out water sampling, looked for life and delved into a new area of science – the presence and impact of microplastics in underground rivers.

We followed strict protocols to produce real science that will be part of research papers in the near future. We went into unexplored branches of the cave, equipped with laser and other surveying tools that will help to build better maps for future explorers.

Finding your way

It is easy to get lost in a cave. My brain was constantly mapping our surroundings, trying to remember landmarks. It was really hard to navigate through them at the beginning, but after a while I learned how to recognise landmarks and refine my ”navigation algorithm”. By the end of the mission, we were all much better at it.

We had experienced speleologists and safety experts train and work with us during the course, showing us all necessary rope techniques to stay safe. I have a huge respect for them and their work under these extreme conditions.

We scouted huge caverns that could host entire cathedrals and city highways. That science-fiction sight transported me to a not-so-distant future where caves on Moon and Mars could become safe havens with stable thermal environments and protection from cosmic radiation.

During the second part of the mission, my fellow ‘cavenauts’ chose me as a commander. Despite my experience as the commander of the International Space Station, this was a new challenge for me, since life in a cave has its own special challenges every day.

As in space, as a commander within a team of nearly equally experienced professionals, my main role was that of a coordinator. Rather than imposing, I chose to look for consensus and did not hesitate to ask my fellow explorers for advice. As a leader, you never want to stop learning from your team, and you should constantly adapt to new situations.

Back to Earth

Coming back to the surface resembled my landing experience in the steppes of Kazakhstan at the end of my space missions in many ways. The smells and colours of Earth hit me, together with a strong sense of accomplishment and camaraderie towards my colleagues. We entered the cave as friends, and as such we left it.

ESA astronaut Alexander Gerst returns to the surface after six days of underground exploration. Credits: ESA–A. Romeo.

When I reflect on this parallel world under our feet, unseen and mostly ignored, I cannot help but think of Jules Verne and his book A journey to the centre of Earth. The CAVES training campaign has been an eye-opener for me – there is so much to explore and learn from the underground.

My next training adventure will take me to another hostile world – Antarctica. I will be collecting meteorites at minus 40°C as part of the scientific ANSMET expedition, and I will have the chance to learn exploration techniques in the frozen lands of the Earth’s South Pole that are very similar to lunar exploration. I can’t wait.

Alexander Gerst, ESA astronaut

Discussion: one comment

I am a ESA retired system engineer. I worked in EO mission design. In my young years I did a lot of caving. Later i thought often o how similar would be EVA from cave abseiling in the dark up or down. Nevertheless I never try to check it out in reality. I left caving as soon as I started working at ESA