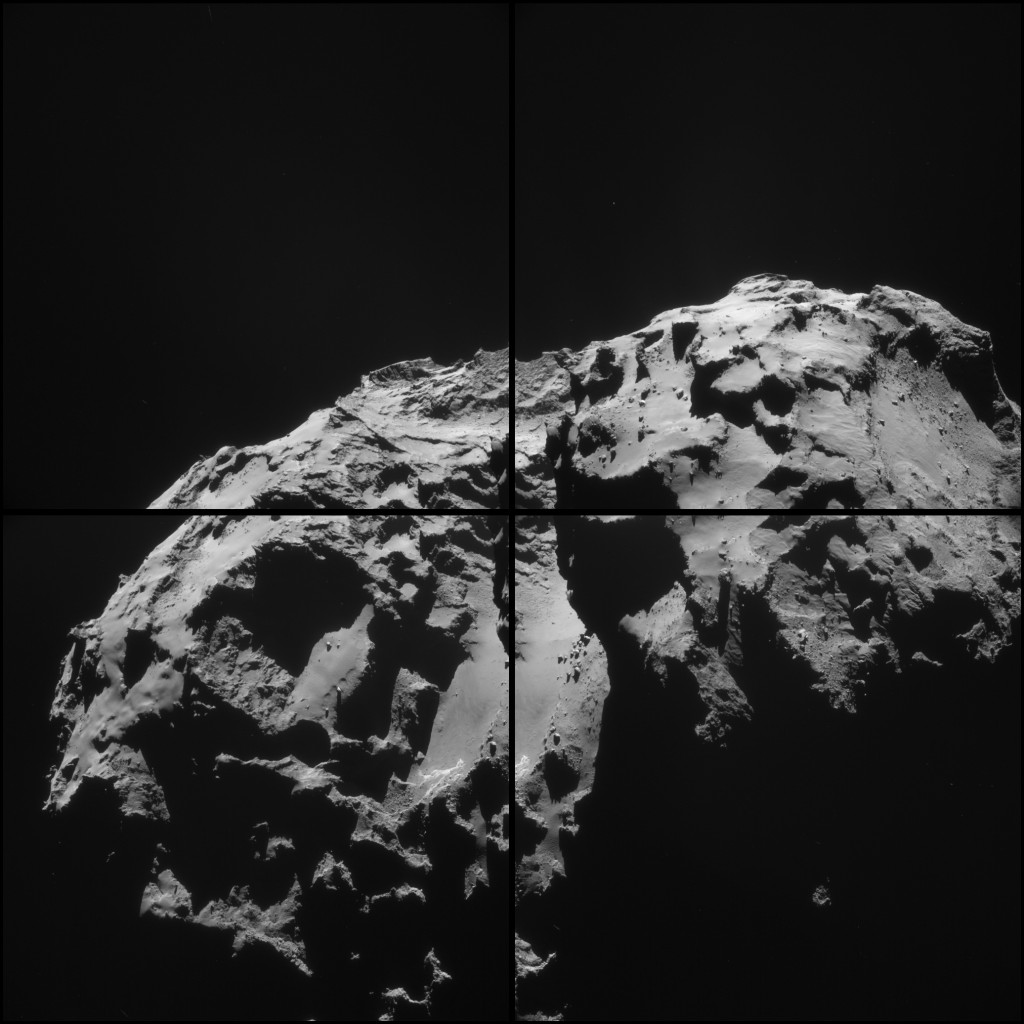

This four-image mosaic comprises images taken from a distance of 27.5 km from the centre of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko on 8 January. The image resolution at this distance is about 2.3 m/pixel and the individual 1024 x 1024 frames measure about 2.4 km across. The mosaic measures 4.3 x 3.9 km.

Four image mosaic comprising images taken on 8 January 2015. Rotation and translation of the comet during the imaging sequence make it difficult to create an accurate mosaic, so always refer to the individual images before drawing conclusions about any strange structures or low intensity extended emission. Credits: ESA/Rosetta/NAVCAM – CC BY-SA IGO 3.0

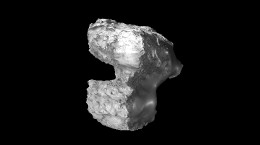

In this view the smaller of the comet’s two lobes is to the right, presenting a side-on look into the large, roughly 1 km-wide depression towards the edge of the mosaic. The rugged outline of the smaller lobe can be traced into the shadows, creating a nice contrast against the smooth neck region in the centre of the image. As noted in the 9 December CometWatch this portion of the neck has some particularly interesting features, such as the bright, exposed cliffs, the curved trough-like features and dark markings in the dusty layer.

To the left, the image offers a striking view of the large comet lobe, in particular the steep, layered cliff face that towers above a smoother, dust-covered ledge. At its edge, it appears as though some of the dust may have slipped away. Towards the background, ridges seem to cut through the terrain, while several flat-topped plateaus are set along the horizon.

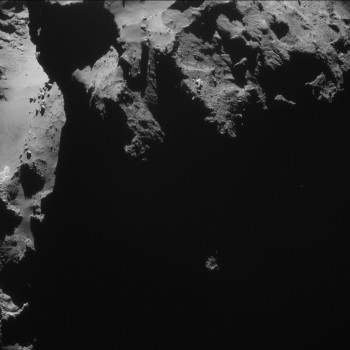

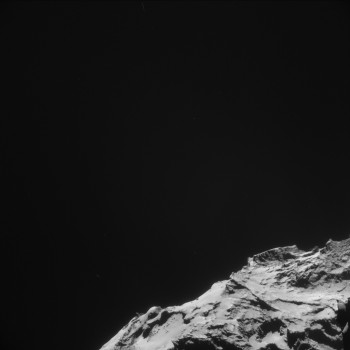

The four individual 1024 x 1024 frames, along with a montage of the four frames, are provided below:

Discussion: 18 comments

Very interesting changes in the neck area – I have posted something about them here:

https://www.unmannedspaceflight.com/index.php?showtopic=7935&pid=216982&st=75&#entry216982

Some features disappear, some appear. I can’t see any changes elsewhere on the nucleus… yet.

Hi Phil, yep, these were some of the possible changes I’d noted in an earlier CometWatch: https://blogs.esa.int/rosetta/2014/12/11/cometwatch-9-december/

Thanks for setting the images side-by-side for a good comparison!

Hi Emily – yes, you did note changes here in December, but these are new changes since then.

So I see! 🙂

Comparative image series of the topographic feature informally known as “The Ampitheater” August 2014 – January 2015

https://univ.smugmug.com/Rosetta-Philae-Mission/Rosetta-Comparative-Series/i-NhxqBbf/0/L/_compar-ampitheater_v2-L.png

Changes in Surface Due to Dust Jet Activity on North Polar Plain

20 October, 9 Dec 14 and 8 Jan 15 Navcams

https://univ.smugmug.com/Rosetta-Philae-Mission/Rosetta-Comparative-Series/i-3LccZVR/0/L/_compar_20-oct-14_9-dec-14_8-jan-15_vent_activity–v2-L.png

–Bill

Thanks Bill, nice documenting (this applies to your many previous posts, too! 🙂 )

I’m particularly enjoying looking out for possible changes in those curved trough-like features in the neck region, so was pleased to see what look like new ones in this image. Fascinating world!

fluidized bed:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fluidized_bed

It has been mentioned before I know, but now substantiated (again too!) by some apparent outgassing.

Question: why “mushroom ring” (quasi circular patterns) and / or linear patterns? Fluid dynamics knowledge out there?

If this is a fluidized bed then maybe Cheops is floating at the surface.

Months ago I speculated Cheops and the likes of it had precipitated from above, now it seems more likely from below! If indeed so the densities of these “floating boulders” must be low and surely a lot lower than that of the material in the plain. Would it be possible that Cheops is a porous structure, that originately consisted of larger amounts of CO / CO2 that sublimated (by the time of Rosetas arrival?) leaving an aerogel of higher sublimation point compounds? Has to be something like that.. And again: this is a previously discussed subject as most will be unless something happens.

We don’t know the depth of the dust below Cheops. but if it is of the order of 20cm as at Philae’s first touchdown point, could this be enough to support a boulder like Cheops – the density of which is unknown? In Earth’s gravity rocks can lie on top of dry sand. Mixed dry material when shaken lets the fine material sink and the coarse material rise to the surface. I’m no expert on all this but it seems to me that there are plenty of Earth like explanations for what we see (or think we see?) in these pictures. While 67P is indeed a strange and unusual place, the explanations for what is happening might be more mundane. And the really significant activity is still many months away.

To answer my own question it does appear common (youtube) that gasses leave fluidized beds in bubbles. As the surface of the “plain” (Imhotep, was it?) are not actually tuned to be fluidbeds at all times, once a bubble has left the surface, a splatter remains until a new disturbance remodels the surface. I predict this to be the entertainment of the next weeks.

Hi Jacob. Fluidized beds take smallest particles to surface. Vibration and sound waves the other way 🙂

Both phenomena inter-play constructing a beautiful and variate landscape.

Emily, I’m glad that we a now seeing surface changes. Maybe we’ll even catch it in the act!

The “North Polar Plain” is one of the 3-4 areas I’ve monitored since the beginning. It is clearly in a current active area, as evidenced by the visible dust jets, and with the particles being ejected upward there are a percentage that will fall back and onto The Plain and surrounding terraces. And located near the axis the return trajectories are going to concentrate in this area instead of being “sprayed around” in more equatorial locations. And since there is an ever-growing accumulation of these deposits on the terraces they will periodically exceed the angle of repose and “slump” in a landslide, so we’ll see much mass-wasting processes. That last “surfaces changes” image is at the foot of the cliff below “The Ampitheatre”, Landing Site A..

And the Geomorph is fascinating. I’ve got dozens of little puzzle pieces on my (virtual) table that are starting to fit into a nice picture.

What a wonderful little world!

–Bill

PS– BTW, the hint might be dropped to The Suits upstairs to issue a list of major place names so we can all be on the same page discussing this. I ‘know there are IAU procedures and all, but there may be a loophole for informal names…

🙂

Good link on fluidized beds, Jacob!

Years ago as a Geotechnical Grunt I worked on a team that sampled smoke stack emissions at coal-fired power plants and spent hours watching fly-ash seep from joints and move around as a fluidized deposit. And with certain impact and volcanic processes “ash cloud” can act like a fluid, so who knows what can happen in a microgravity, micro-Bar environment with nano- and micro-sized nascent silicates and organics particles.

This place is really going to be hopping come Perihelion!

–Bill

Thanks Bill and Phil for the comparison images. There appear to be two extra circular features at the top right of the “Amphitheatre” which I could not recall seeing before and Bills images confirm this. The deep caves just along from there seem to be the origin of the odd “coral sheet” protrusions seen so clearly on the Jan 3rd image. Those more solid looking, in all likelihood less volatile, cave walls must take a long time to erode.

The thought occurs to me of how much bigger 67P was in the past and that what we see now was once buried deep in the core of a much bigger object. If this is indeed the case then gravitational pressure and impact shock may account for the partial consolidation and stratification these layers of different refractoriness imply.

I agree with Jacob that there appears to be some sort of fluidisation and flow, but I am also wondering if those “horseshoe” shaped and linear scarps are not just underlying terrain beginning to show through as the depth of the dust layer is reduced by the outgassing. It would be easy to suggest the more circular features are the result of jets of sublimating gas passing up through the porous dust and they are the evidence of the streamers, but without cause and effect in the same image that would be unwise me thinks. The area where these depressions are is on a slope so if volatile ices just below the surface have sublimated away, one might guess the dust has slipped in to fill the void, leaving a wall of undisturbed, less volatile material in much the same way a waterfall erodes back into a cliff. Many, many semicircular and near circular features from small to very large show this morphology all over the comet. It will be very interesting to see how these features evolve and whether we start to notice them elsewhere, on the larger dusty plains especially.

This may be more to do with viewing angle and lighting, but the area around Agilkia seems to be more corrugated than two months ago, the big “X” feature is a lot more defined and the ridge next to Philae’s first touchdown point is more pronounced. Again I wonder if this is dust loss revealing more of the underlying terrain rather than movement of the dust across the surface. We have seen dust leaving the comet on a continuous basis for over four months, that must amount to tens of thousands of tonnes, it would be surprising if we were not to start to see a visibly less soft edged terrain.

“… what we see now was once buried deep in the core of a much bigger object.” Given that in term of mass water and not C02 is the dominant emited gas, I follow your line of tought, Robin 🙂

My take on this mosaic:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/105035663@N07/16378643566/in/photostream/

Levels adjusted:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/105035663@N07/16403718162/in/photostream/