The long-term sustainability of outer space activities is something that Clean Space has been actively pursuing for years. Now it is finally becoming a shared goal for the Member States of the United Nations.

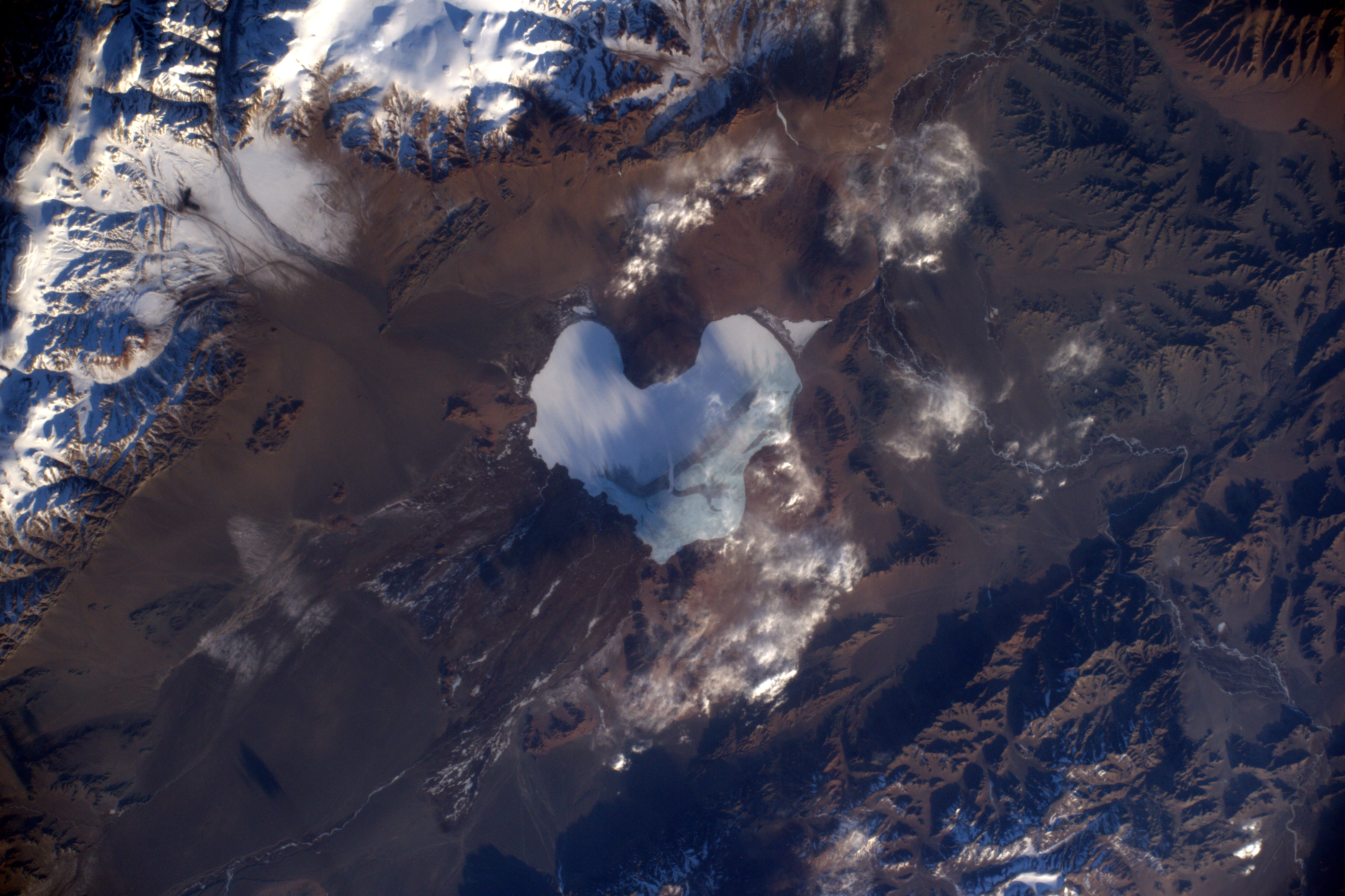

Heart-Shaped laked

Credits: ESA / Thomas Pesquet

The Committee on the Peaceful Use of Outer Space (COPUOS) of the United Nations, a board that works to guarantee that space activities promote peace, security and development for all of humankind , has reached consensus, after years of discussion, on a first set of guidelines for the long-term sustainability of outer space activities.

But, what does “sustainability of space activities” mean exactly?

According to the first set of the guidelines, the term is defined “as the conduct of space activities in a manner that balances the objectives of access to the exploration and use of outer space by all States and governmental and non-governmental entities only for peaceful purposes with the need to preserve the outer space environment in such a manner that takes into account the needs of current and future generations.”

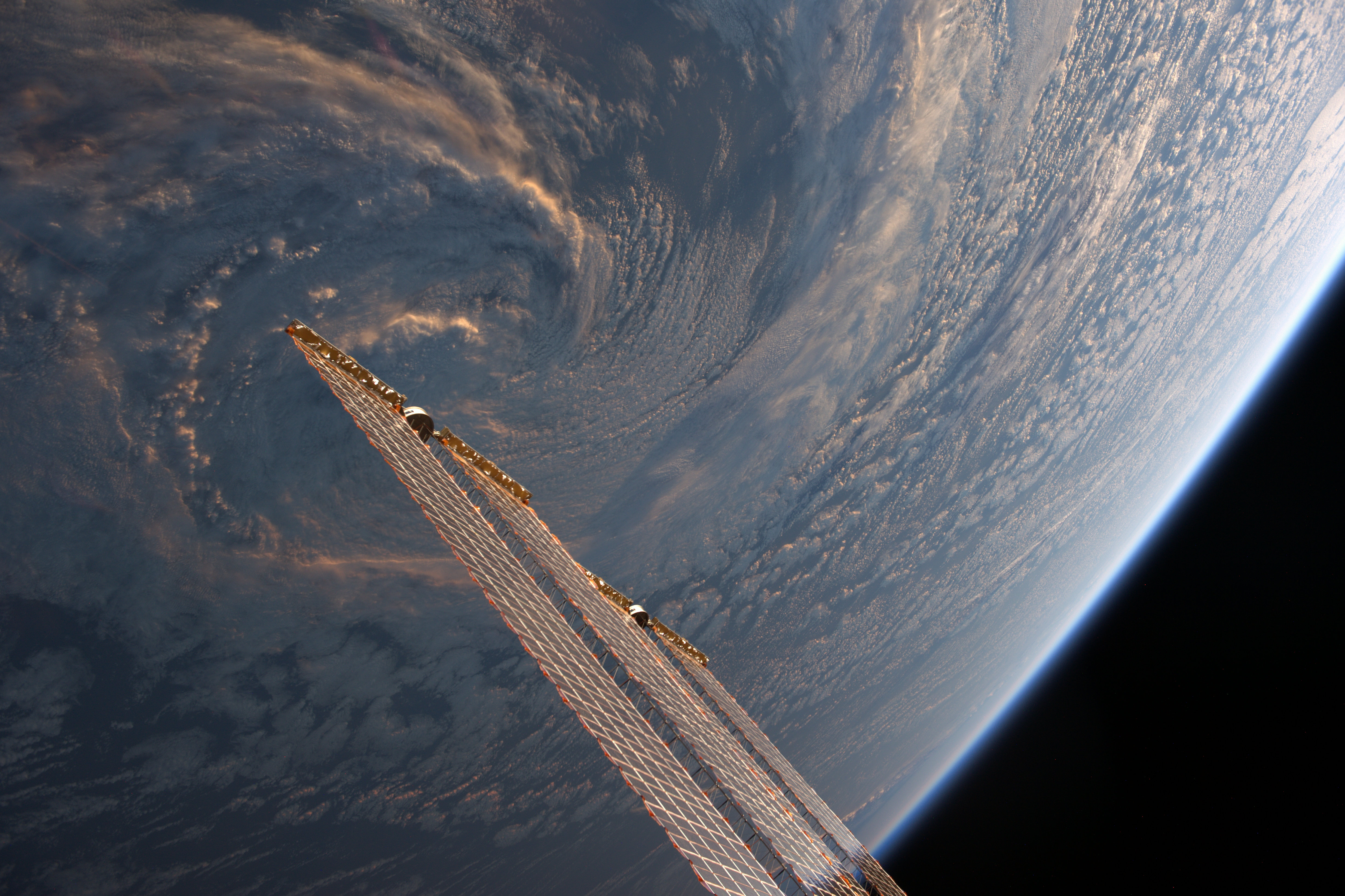

Storm at dusk

Credits: Thomas Pesquet / ESA

The overall scope and meaning of the COPUOS document resonates fully with Clean Space’s work and mission, with at least two of these guidelines turning out to be very important for our work.

Guideline 27 calls for “Promot(ing) and support(ing) research into the development of ways to support sustainable exploration and use of outer space”. In particular, it states (27.3) that “States and intergovernmental organizations should promote the development of technologies that minimize the environmental impact of manufacturing and launching space assets and that maximize the use of renewable resources and the reusability or repurposing of space assets to enhance the long-term sustainability of those activities.”

The action expressed in this sentence is perfectly aligned with our Clean Space Eco-Design branch: to evaluate the environmental impacts and identify the main sources of pollution, and to propose technical solutions to reduce their impacts.

To assess impacts, it is necessary to carry out scientific evaluations on the entire life-cycle of the studied space mission. This can be done through a proper Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). Until recently though, this was easier said than done because the peculiarities of the space sector made quite hard to use the existing LCA tools.

Today, that is not the case anymore. ESA has just published its first Space system Life Assessment Cycle guidelines which provide industry with a framework for performing “comprehensive quantitative assessments and consistent environmental declarations for complete space system as well as individual hardware equipment, components, material and processes.”

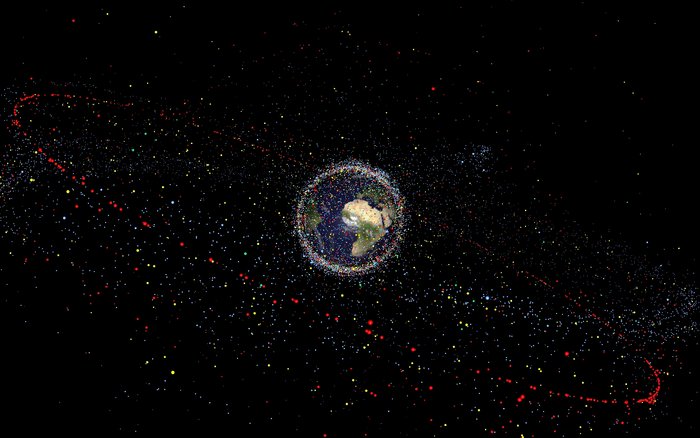

The second guideline of high relevance for us is Guideline 28: “Investigate and consider new measures to manage the space debris population in the long term.”

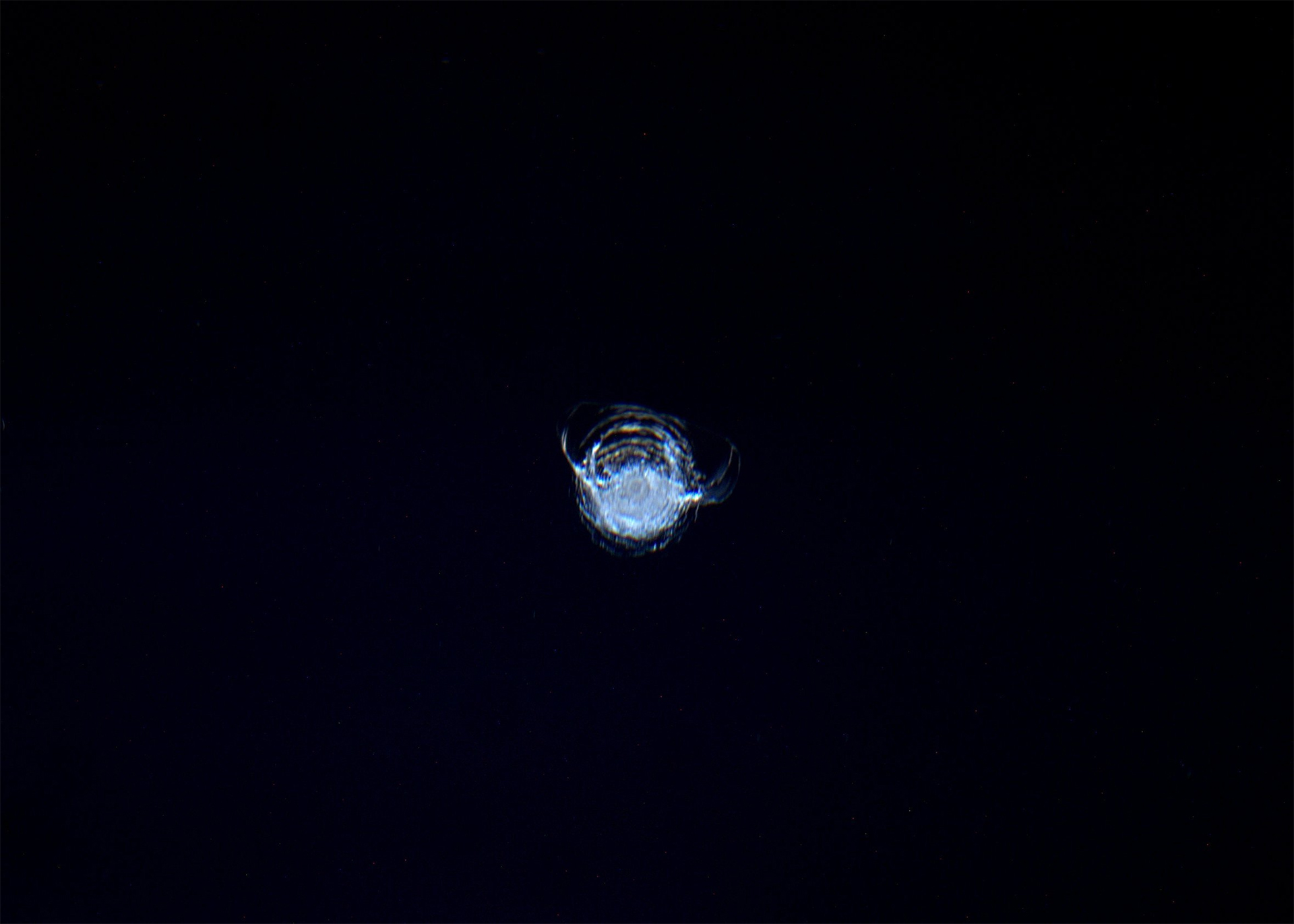

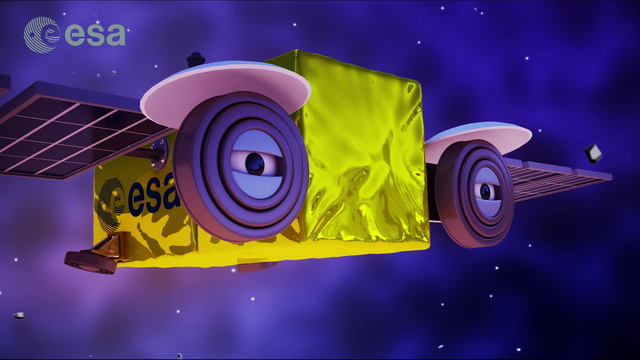

Impact chip on the ISS. ESA’s Clean Space team carries out studies and technological developments to reduce the risks coming from space debris.

The first article (28.1) states: “States and international organisations should investigate the necessity and feasibility of possible new measures, including technological solutions, and consider the implementation thereof, in order to address the evolution of and manage the space debris population in the long term (…).”

At Clean Space we have been working in this direction through CleanSat, the project that pursues the development of technologies needed to comply with Space Debris Mitigation (SDM) requirements. Our CleanSat roadmap already encompasses much of what is demanded in the guideline, especially in articles 28.3 and 28.4,.

Article 28.3, for instance, mentions “advanced measures for spacecraft passivation and post-mission disposal and designs to enhance the disintegration of space systems during uncontrolled atmospheric re-entry”. This is one of the cornerstones of CleanSat: European industry and ESA have already started to study passivation technologies to avoid both battery break-ups and explosions due to propulsion system issues.

Safe reentry is a concern expressed by the committee in article 28.4 stating that “such new measures aimed at ensuring the sustainability of space activity and involving either controlled or uncontrolled re-entries should not pose an undue risk to people or property, including through environmental pollution caused by hazardous substances.”

We could not agree more with this statement and are carrying out numerous activities to develop controlled break-up techniques and to design demisable elements that allow a satellite to burn up completely while reentering Earth’s atmosphere.

It is really encouraging to see that the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space recognises, as ESA does, that “the long-term sustainability of outer space activities is of interest and importance not only for current and aspiring participants, but also for the international community as a whole.”

Discussion: no comments