Spacecraft and robots cruising to the Red Planet – and back – need a brain and instructions to follow. Here is the story of a software engineer behind the two European contributions to the Mars Sample Return campaign, in his own words. Meet Cristian Englert, or how he likes to introduce himself, the software guy for Mars.

Hi there! I am Cristian Englert, also known as the software guy, or “Software issue? Again?!? Criiiiis!!!”

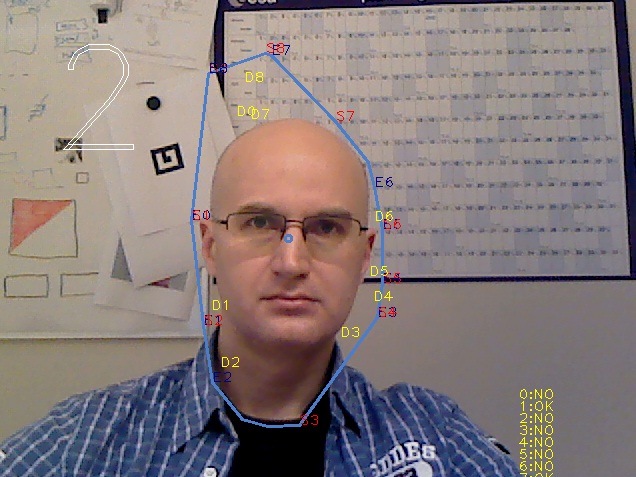

And sometimes, on very quiet days, the guy to ask about augmented or virtual reality, the metaverse, machine learning, computer games or the philosophical significance of the number 42.

You guessed it, I am the software responsible for two of the major European Mars Sample Return components: the Earth Return Orbiter and the Sample Transfer Arm.

It all happened about four years ago. I have a long experience with human and robotic exploration projects, and at the time I was one of the two flight software engineers supporting the development of the ExoMars rover Rosalind Franklin. I got invited to the office of a system engineer named Kelly Geelen.

“Hey,” she told me (and I paraphrase), “we have this mission to retrieve samples from Mars and bring them back to Earth. We are starting to define the system-level requirements and we need people to kick this off…”

Why do I paraphrase? Because those very few words were enough for me to decide that I was in love with the concept and everything else was just details. All I wanted to do was to ask “Where do I sign?” And from that day on, the project hasn’t disappointed me one bit.

One might say software is the blood of a spacecraft; others might say it is its nervous system. But metaphors aside, the software is everywhere, so I have to be everywhere. There is, of course, the central software, the one that deals with the main activities of the spacecraft. But that’s not all; almost every small unit and piece of equipment runs some type of software inside. The ground segment and the simulators used for verification and validation rely on software as well. And some lucky person must take care of all this. I sometimes wish I could clone myself three or four times .

Developing a spacecraft is a complex and challenging task, which often requires working on an ambitious and unfriendly schedule. When this spacecraft is involved in a planetary exploration mission the complexity scales up.

Every piece of the puzzle must come in place at the right time, because launch windows to other planets are limited and the cost of missing them can be very steep. Now, do you remember that nervous system paradigm? Let’s look a bit at the spacecraft’s brain, which is the central software.

While the smaller pieces, the organs, might not be entirely new developments, the central software is, for a non-standard mission like the Mars Sample Return, mostly new. And we build something like this in an iterative manner, with several versions covering specific functionalities, each one more complex than its predecessor. Each milestone and each review of the central software is a tense affair. Will everything be ready in time? The answer is rarely simple, and often the only mitigation comes from the software’s inherent ability to adapt to the unexpected.

Did you follow the amazing Mars live broadcast last week? That is a perfect example of the flexibility the software provides. Through the magic of new software, an old camera built originally with a narrow engineering purpose was transformed into a live streaming device. Just like that, a clever piece of software can give new life to spacecraft that were supposed to have been decommissioned long ago.

Reaching for Mars was always a dream of mine: half personal choice, half a cultural one, since I grew up with the books of H. G. Wells, Ray Bradbury and Kim Stanley Robinson. We are close to an inflection point in technology and the conquest of our neighbouring planet is part of redefining humankind’s relationship with the Universe.

Honestly, what’s not to like? Detective story with finding life on Mars, check. Cliffhanger rendezvous and capture of the Orbiting Sample, check. Happy ending with the spacecraft delivering the samples home, check.

People in Europe should be aware that we are active players in this game, as part of a transatlantic community of scientists and engineers. We don’t have a movie like “The Martian” to promote our role and our ambitions, but we should spread the word and build, particularly in the young generation, the confidence to dream big and, this time not metaphorically, reach for the stars .

Discussion: one comment

Gracias. Esta bien, creo, es un buen trabajo y la idea es muy buena. Pero a mi me gustaría algo aun mejor, algo que pudiera hacer que l@s qinceaner@s engancharse y pudiesen comenzar a encontrar puestos de trabajo, remunerados obviamente, en proyectos como estos y/o similares. En este sentido seria conveniente dedicar mas medios a la adecuada divulgacion y promocion de la participacion estudiantil. Saludos cordiales