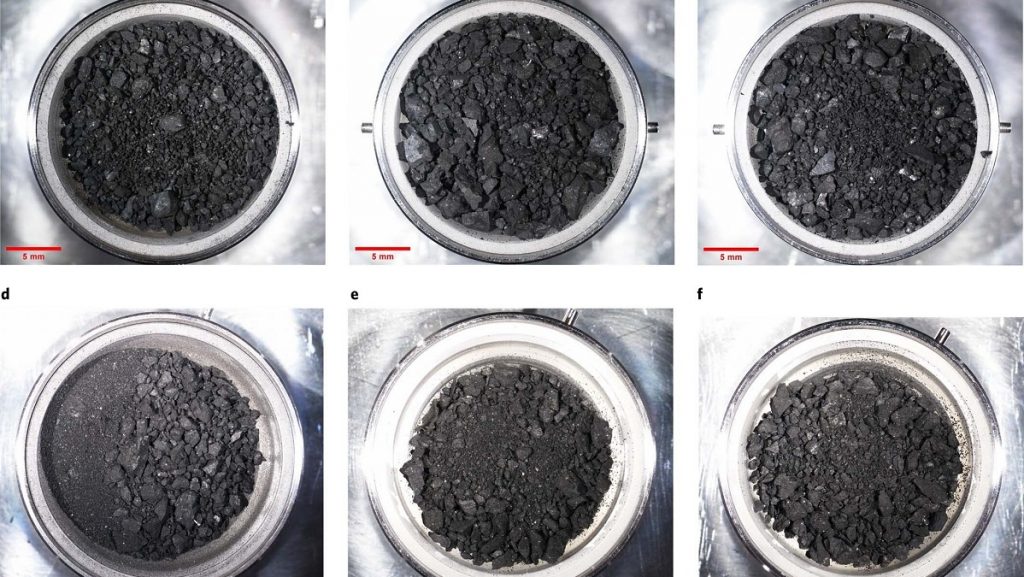

The gift came to Earth from the Japanese Hayabusa-2 mission in 2020. The spacecraft dropped off a capsule with 5,4 grams of material from asteroid Ryugu in Australia. The samples were then transported to a laboratory in Japan.

“There were far more rock fragments than we were expecting – that was an amazing surprise,” says Audrey.

She was part of the international research team that ran the first chemical analyses of Ryugu rock samples. The team wanted to reveal the asteroid’s true nature for insights into the origins of our Solar System and life on Earth.

The real plus for the scientists was to be able to analyse the most pristine asteroid samples ever returned to our planet – they didn’t suffer any modification during the re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere or until their recovery from their landing site as meteorites do when they fall to Earth.

Mars attraction

Audrey’s experience with the Japanese mission is quite similar to what is in store for the Mars Sample Return (MSR) campaign. Scientists worldwide will be eagerly waiting for a set of tubes filled with pristine samples from the Red Planet to be analysed in the best labs on Earth.

Audrey Bouvier is one of the European members of the Mars Sample Return Campaign Science Group. She is also professor of Planetology at the Bavarian Research Geoinstitute of the University of Bayreuth in Germany.

Audrey has been studying meteorites for almost two decades now. She started her research career in France, and has worked in the United States, Canada, and now Germany.

Most of her research is focused on the chemical and chronological aspects. Audrey aims to understand the origin and magmatic evolution of Mars, as well as the impact history of the Red Planet.

Not long ago she had the chance to hunt for meteorites in the Atacama Desert in Chile during an international expedition to characterise the last two million years of the meteorite influx on Earth.

What happens in the lab

The cosmochemist and geochronologist is familiar with high-precision isotopic measurements of radiogenic nuclides in planetary samples, which can tell us about when and how minerals and rocks formed on Earth and other planets.

“A large part of the research taking place in my laboratory is to develop new tracers of planetary processes by analysing the isotopic composition of trace elements contained in rock samples. We use cutting-edge analytical techniques to minimise terrestrial contamination and the mass required for the analysis of such rare and precious planetary samples,” she explains.

“All elements of the periodic table, most of them contained in very low abundance in minerals, preserve a mine of information for over four billion years. Each provides a piece of the puzzle to understand our origins in the Solar System,” she says.

Precious Mars samples

Audrey expects that the first set of samples collected at Jezero Crater and just placed on the surface at the Three Forks site will give a good insight into what happened on the martian surface.

“The collected samples are different from any martian meteorites. They will give us new knowledge about what happened early on and deeper in the planet,” she adds.

Audrey has a soft spot for igneous rocks, but any gram of martian soil will be precious to her. She is ready to wait a decade for the samples that will help understand how planets – including our own planet Earth – are so unique.

She will not be alone, nor will she stop working to prepare for the moment. “We are training the next generation of scientists who will carry out the analyses of these very precious samples. We will make the best use of new technologies that will come up by then. The wait is worth it,” she concludes.

Discussion: one comment

Any Plans of Colonizing or Planetary re-engineer Mars?