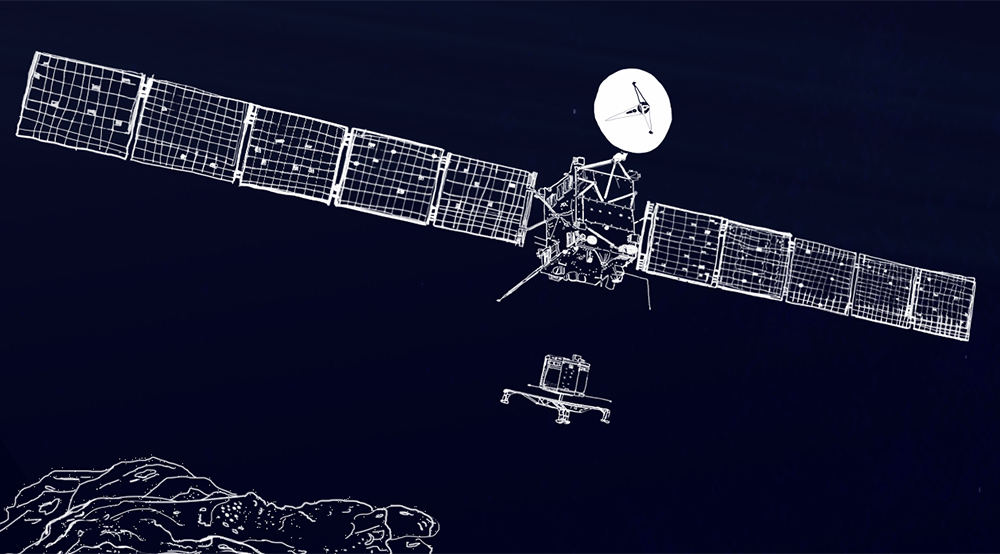

This time last year saw the end of an extraordinary week at ESA’s European Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany. Hundreds of journalists and reporters had gathered to witness an historic endeavour as on 12 November 2014 the Rosetta orbiter deployed the lander Philae on the surface of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. In this blog post, some of our media friends reflect on the events of that memorable week and on one evening in particular.

Late in the evening on 14 November, two days after Philae had landed (and bounced) on the comet, three social-media eye witnesses joined a small team of ESA communicators sitting just outside the mission control room at ESOC. Keeping an eye on Philae as it completed its scientific operations, they tweeted live what could have been the lander’s final contact with Rosetta.

Steven Young, Emily Lakdawalla and Chris Lintott at ESOC on the night between 14 and 15 November 2014. Credit: E. Baldwin

They were Emily Lakdawalla, Chris Lintott and Steven Young, who had been reporting during the week for The Planetary Society’s blog, for the BBC’s Sky at Night programme and for the UK’s Astronomy Now magazine (and Spaceflight Now website), respectively. One year later, we asked them to join us on a trip down memory lane, piecing together their impressions of that hectic week and, in particular, of that remarkable evening.

“I expected it to be similar to the Huygens landing, which I also attended, and it was!” Emily told us.

“I was anticipating doing daily blog entries as well as tweeting everything I could. Based on past experience at events like Mars landings, I also expected to be helping other members of the media understand the science and the background behind the mission.”

Chris also had been at ESOC for the Huygens landing on Saturn’s moon Titan in 2005. “That was thrilling, and the chance to be back for another piece of space history was very exciting indeed.”

This time, he came with co-presenter Maggie Aderin-Pocock and a film crew from BBC’s Sky at Night. “We’d been given an hour-long special to be broadcast on the weekend after the landing, and so while we filmed at ESOC a team back in London were working overnight to put the program together.”

Steven and his US-based colleague Stephen Clark provided live updates on their websites and social media outlets throughout the week, and recorded video interviews with mission officials.

“Although we live in an era of instant communications and live-streaming video, there is no substitute to witnessing history being made first hand,” Steven said.

This is especially true in light of the surprising nature of the landing, with Philae touching down a mere hundred metres from the planned location, but then bouncing repeatedly and ending up more than a kilometre away, in a completely unexpected place.

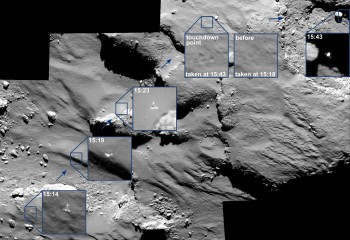

The last moments of Philae’s descent, the imprint of its touchdown, and subsequent drift away from Agilkia was captured by Rosetta’s OSIRIS camera. All times in UT onboard spacecraft time. Credit: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA

“It was very exciting but there was also a lot of confusion about what was really happening way out there in space and inevitable conspiracy theories that things had not gone well,” Emily said.

“I and a few other media – including Steven and Chris, as well as Jonathan Amos, Stuart Clark, Eric Hand, Ivan Semeniuk, and Paul Sutherland – pooled the tidbits of information we had each been told that we could be reasonably confident about, trying to tell a consistent and true story about what was taking place at the comet, about what the engineers knew, and what they didn’t know about Philae’s condition,” she added.

While covering such a unique event live could be very exciting, risks and pitfalls are also on the menu and the reporters needed to be prepared for everything.

“I remember worrying about how we would tell the story of a failed landing: what was being attempted by the team was so audacious that it would have been a tragedy if a failure had meant that the whole Rosetta mission was perceived as a failure,” said Chris.

“Of course, in the end, from a reporter’s point of view things couldn’t have been better. Wonderful scientific results, and a story that kept most of the world on the edge of its seat for days on end.”

In Steven’s recollection, he did not really know what to expect beforehand and that, to him, was the best part of covering the mission.

“It truly was a step into uncharted territory. I joked on the morning of the landing that I expected the day would see the first historic landing on a comet… and the second historic landing on a comet… and the third historic landing on a comet. Turned out to be quite a good prediction!” said Steven.

In hindsight, it sounds like a relatively straightforward story to tell. But being there, trying to make sense of the events as they were unfolding and turning them into stories for a highly demanding audience, was something else entirely.

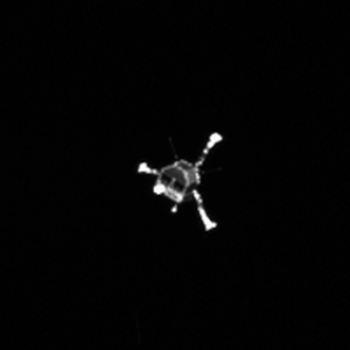

This image from Rosetta’s OSIRIS narrow-angle camera shows the Philae lander at 10:23 GMT (onboard spacecraft time) on 12 November, almost two hours after separation.

Credits: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA

According to Emily, the audience was interested in “solving the puzzle of what had happened after the first touchdown” but their main interest was in the images that Rosetta and Philae would send back.

“Images taken by OSIRIS of Philae descending and floating over the comet, and images taken by Philae of the descent and of the landing site. It’s all about the images; they are what give the audience the feeling that they are standing there on the comet with Philae,” she said.

Chris was very struck by the general public’s thirst for knowledge, with many people caught up in the emotional journey of Rosetta and Philae, but possibly even more curious about the technical and scientific details, asking questions, before and after the landing, about what had been discovered.

“I think the mission really showed that people are interested in both the exciting, romantic stories of spaceflight but also in the nitty-gritty of the data,” Chris said.

“And of course new images were seized upon and sent around the world as soon as they appeared. I hope the imaging teams understand how much sharing what they could meant,” he added.

To Steven, the main questions to answer were rooted in the mission’s three-decade long history. “Were the years of devotion from the scientists and engineers going to pay off? It was a human story as much as a science and engineering story. Achieving such a momentous goal was inspiring,” he told us.

When we asked about their most abiding memories of that week, their thoughts immediately went to the night when Philae ‘fell asleep’ on the comet.

Spacecraft operators on duty at ESOC during the night between 14 and 15 November 2014. Credit: S. Young / Astronomy Now

“No question, the main memory is staring through the glass at the control room, watching that line on that graph drop, indicating the voltage dropping on Philae’s bus, I think. Knowing we were watching the spacecraft go to sleep, possibly forever,” Emily said.

Chris remembered the look on Andrea Accomazzo’s face when he popped into ESOC on the morning of Saturday 15 November, after most of the journalists had left, and found a couple of them still filming outside the gates.

“But he happily gave us a bleary-eyed interview, and that for me symbolised how friendly and helpful the mission control team and the mission’s scientists had been,” said Chris.

“I also keep thinking about our trip to lander control at DLR on the day after the landing, and the calmness with which the scientists negotiated over which instrument would do what during the limited time available,” he added.

But for Chris, too, “the most memorable event has to have been sitting outside mission control with Emily and Steve, broadcasting Philae’s hibernation to the world. I remember watching the line on the graph that marked the power available trend ever downwards, and all the time the data flowed…”

Steven’s memories also went back to that unforgettable evening.

“Although its landing did not go as smoothly as planned, Philae still gathered much science. On the night of 14/15 November as we waited to hear from the lander, the first hope was that all that science would be returned before its batteries ran low,” he said.

The story of the little lander that could kept members of the public worldwide hooked for the entire week, through traditional, online and social media. But on that special night, the main sources of information were the ESA blog and Twitter accounts, and our three social-media eye witnesses and their live tweets.

“I got a lot of followers that week,” recalled Emily, who had been passionately tweeting in the previous days.

“Because there was so much information flying around, I worked really hard to just tweet facts and to answer people’s questions and clear up misconceptions.”

Chris admitted to never having been in the middle of such a busy and lively online situation like the one that took place between mission control and the Twitter-sphere on that evening.

“There was no way I could keep up with the replies that flew past, and Emily’s timeline looked like a slot machine as messages whizzed past,” he said.

“I think that our followers felt they were there with us, and I hope someone in mission control realised they had a world of spaceflight fanatics ‘watching’. I still get somewhat emotional thinking about it a year later.”

The mission control room at ESOC on the night between 14 and 15 November 2014. Credit: S. Young / Astronomy Now

Looking back on the roller-coaster of events that occurred in those hours, Steven said: “It was a tense time waiting for the signal from Philae to be relayed by Rosetta. When the data started streaming across the screens of mission control, we willed it to keep going.”

But it was not just about downlinking the data obtained up until that point. The hope that Philae would one day wake up was also driving the operations, and it was crucial to leave the lander in the most favourable position for the months to come.

“Once that hurdle had been reached and all the science data was on the ground, our hopes moved on to the lander being able to shunt itself out of its shady spot and for the Sun to recharge its dwindling power supply,” Steven recalled.

“For a while Philae’s precarious position was forgotten, but the cruel reality of its exhausted batteries became apparent on the screens in the control centre. Battery voltages had held up well but were now plummeting. It was not long before they reached critical levels and Philae fell silent.”

Clearly, the emotional charge of all those present and involved was very high. “Although it felt like a friend had slipped away, it was clear from the atmosphere in mission control that Philae had done its job despite the difficult circumstances,” added Steven.

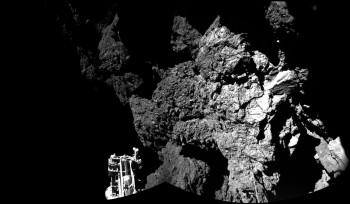

Philae’s view of the cliffs at Abydos – one of the lander’s three feet can be seen in the foreground.

Credits: ESA/Rosetta/Philae/CIVA

However, the reporters – and their audiences – still have lots of questions about the nature of comets.

“I wish Philae had woken up and done a little more science! I was excited at the wake-up in June, but evidently the lander was teasing us!” commented Emily.

Chris reckoned that “it’s obvious we’re only just at the beginning of understanding what the mission has told us about the comet,” and he is eagerly looking forward to more scientific discoveries.

“I’m waiting for the team to catch their breath and switch from telling us about what they’ve found to working out why the comet is the way it is,” he added.

Emily sounded slightly more gloomy. “I feel like I’ve been teased about what the surface of a comet is really like. We know it’s hard, and pebbly, but we didn’t really get to learn what it was made of.”

But she also shared some wishful thinking with us: “I want to send another mission to a comet.”

On the other hand, Chris wittily noted how he found out about Philae’s wake-up “with intense annoyance.” Of course, what he meant is that the timing of this unexpected, but much anticipated, event was very bad for him and his colleagues at Sky at Night.

“It happened the night before our monthly program went out, and I was stuck in the US. The team scrambled magnificently to re-edit, though.”

Shortly after Philae came briefly back to life and made contact with Rosetta, space enthusiasts across the world had another historic moment to witness this summer – the New Horizons probe flying by Pluto on 14 July 2015. Emily, Chris and Steven reported this event from the mission operations centre at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, USA.

“Pluto is weirder, more colourful, more diverse than anything I imagined,” Emily told us. “I think both Rosetta and New Horizons have shown us that you just can’t predict what any Solar System world will look like, large or small, until you visit them up close,” she added.

Chris was there with the Sky at Night team. “I hadn’t realised how different a flyby would feel from a landing: whereas Philae delivered a week or so of drama, New Horizons was an immediate success,” he said.

“Both were remarkable moments in history, though, and it’s been such a privilege to tell the story of these missions.”

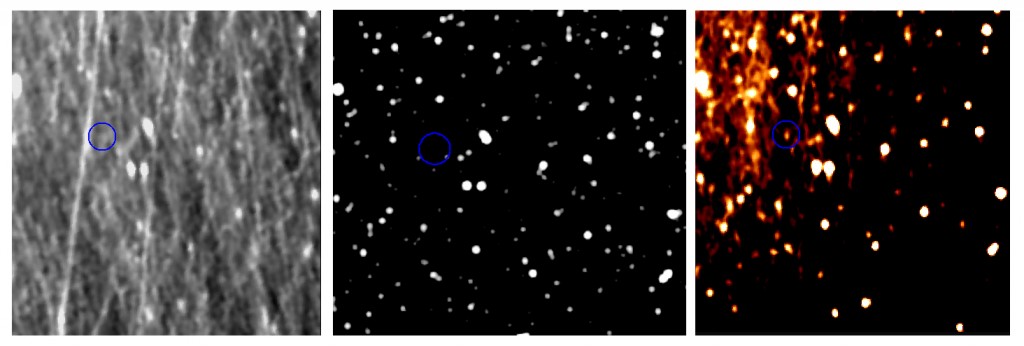

Rosetta’s view of the dwarf planet Pluto obtained with the scientific imaging system OSIRIS on 12 July 2015. Left: The unprocessed image is obscured by dust grains in comet 67P’s coma. Middle: Pluto’s background of stars as seen from Rosetta. Right: The processed image shows Pluto as a bright spot within the blue circle. Credits: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA

For Steven too, the two experiences were quite different. As he recalls, “It was a great thrill to witness the Pluto flyby from mission control in Maryland and it was great to see so many colleagues from the Philae landing. The two events were historic but very different to cover as a reporter. Compared to the fast pace of events of the Philae landing, New Horizons was like watching a slow motion replay, equally exciting but stretched over many months.”

But as Emily reminds us, next year will also be a very exciting year for planetary science, with Juno arriving at Jupiter, and Cassini completing its exploration of the moons of Saturn and beginning its final focus on Saturn’s rings.

And of course, there is still one more comet “landing” to look forward to: as outlined in a recent post, in September 2016, the Rosetta mission will end with a controlled impact of the orbiter on the surface of 67P/C-G.

“I’m looking forward to a continuing bounty of data from Pluto, Ceres, and 67P, and to Rosetta’s final act, descending ever closer to the comet,” Emily commented.

Chris sees the final landing as a fitting end to the mission. “I think the excitement around the end of mission will be quite something – it’ll be good to help remind people of this epic journey we’ve all been on.”

Steve expresses the hopes of many people when he says: “I’m very much looking forward to seeing 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko in fine detail when Rosetta makes its slow descent towards the comet at the end of its mission and, while it’s highly unlikely to survive a touchdown, wouldn’t it be amazing to see more images and science from the surface of a comet?”

—

Emily Lakdawalla is a geologist, science communicator and advocate for the exploration of all of the worlds of our Solar System. She blogs at the Planetary Society: https://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/

You can follow Emily on Twitter: @elakdawalla

Chris Lintott is Professor of Astrophysics and Citizen Science Lead in the Department of Physics, University of Oxford, UK. He is also a journalist and presenter of the BBC series The Sky at Night: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b006mk7h

You can follow Chris on Twitter: @chrislintott

Steven Young is the publisher of Astronomy Now, the UK’s longest running monthly astronomy magazine (https://astronomynow.com), and of the Spaceflight Now website (https://spaceflightnow.com/).

You can follow Steven on Twitter: @stevenyoungsfn

Discussion: 3 comments

Heartwarming, an feeling a [guest] Insider for the first time, Claudia 🙂

A very interesting piece. Many thanks.

It was great to have you at mission control centre with us. It still have tears in my eyes. Thanks for sharing our work with the world. Andrea