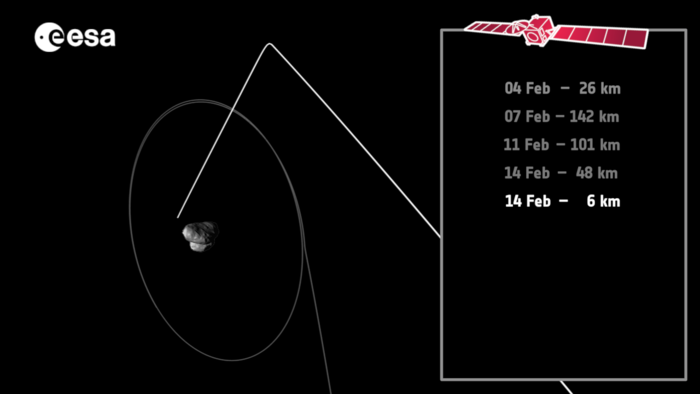

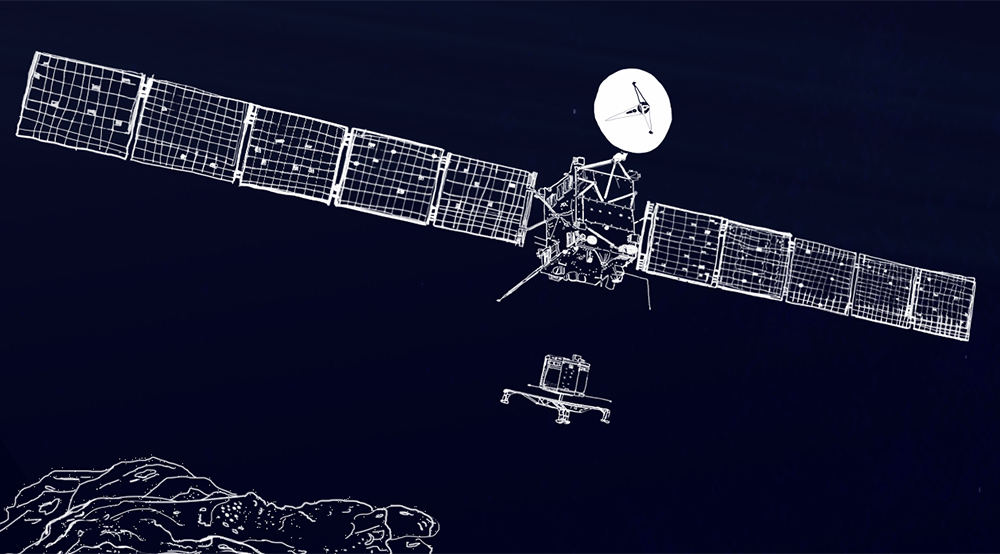

Rosetta is preparing to make a close encounter with its comet tomorrow, on 14 February, passing just 6 km from the surface.

On 4 February, Rosetta began manoeuvring onto a series of new trajectories that will align the spacecraft for this week’s encounter. The series of thruster burns are happening (or have happened) as follows (distances are indicated from comet surface):

4 Feb – Depart from 26-km terminator orbit

7 Feb – Achieve 142 km from comet, then turn back

11 Feb – Arc back down to 101 km

14 Feb – Reach 50 km stand-off distance; turn and burn for the closest flyby arc

14 Feb – Conduct 6 km flyby at 12:40:50c GMT

The closest pass occurs over the comet’s larger lobe, above the Imhotep region (click on the image below to watch).

Note that, in the main science phase, Rosetta’s trajectory is being set by the Rosetta Science Ground Segment (RSGS) at ESAC, on a 16-week planning calendar (known as the LTP – the ‘long term planning’ process), and is fully optimised for the suite of instruments on board.

This means that 16 weeks before the start of each LTP cycle, RSGS proposes a trajectory for that LTP. This trajectory is then checked, against spacecraft and mission constraints, among other factors, at ESOC by the flight dynamics team.

While closest approach on 14 February is certainly a significant event for science observations, for the flight control team at ESOC, it’s a fairly routine operation and just one more activity during the main science phase.

Very short week in, very short week out

Since the intense manoeuvring and operations of 2014, the flight control team have adopted a regular weekly planning cycle. This covers two ‘VSTPs’ (very short term plans) covering Wednesdays to Saturdays (planned on Mondays) and Saturdays to Wednesdays (planned on Thursdays). Specifically:

- On planning days, last data inputs come in early in the morning – for optical navigation data, i.e. NavCam images, and radiometric data from the ground stations

- Production of all flight dynamics commands needed for the upcoming VSTP and covering (among others) trajectory and pointing strategy for that VSTP

- Merging of flight dynamics products with instrument commands and spacecraft platform commands

- Making sure the merge is conflict free (reconcile instrument, spacecraft and mission constraints)

- Generating, as output, not only commands to be uploaded to the spacecraft, but as well all data files needed on ground. These include, for example, the ground tracking station instructions for ESTRACK and NASA deep space stations for that VSTP, and the instructions for the automation tool in the ground control system.

Flybys – the new normal

For the rest of the current mission plan in 2015, in fact, Rosetta will always conduct flybys, and, based on predictions of increasing cometary activity, can no longer be manoeuvred so close to the comet as to be in a gravitationally bound orbit.

The net effect is that the workload for mission planning has settled into a more or less predictable, if still challenging, cycle. And, when not at work at ESOC during the week, the flight control team remain on call day/night/weekends.

Navigation: five times daily

The flight dynamics team at ESOC take optical images five times a day using Rosetta’s navigation camera, the NavCam. These images are then used in the optical navigation process to reconstruct the position and trajectory of Rosetta with respect to 67P.

“The NavCam is crucial for relative navigation and knowing where we are with respect to the comet,” says Rosetta Spacecraft Operations Manager Sylvain Lodiot.

He explains that a set of parallel trajectory plans are maintained; one set describing the ‘preferred’ case (making certain assumptions on comet activity), and the other describing the ‘high activity’ case (which is a fall back solution in case the preferred case can’t be flown, and is further from the comet). Also, the operations teams, with the approval of the mission manager, would command a transition to the high activity case if the optical navigation process were to fail for any reason.

Low bit-rate season

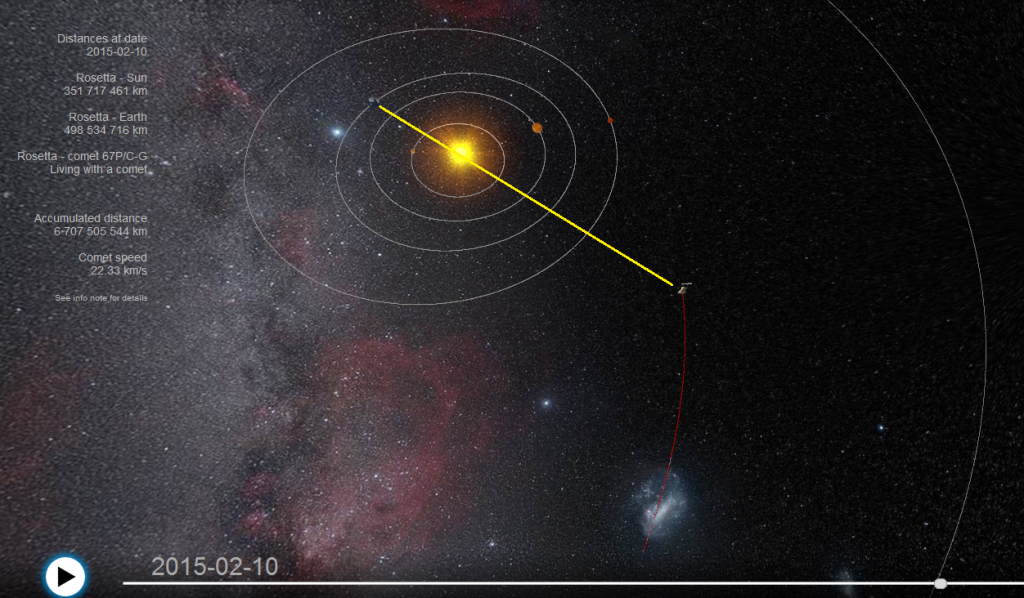

Beginning on 26 January, the comet and Rosetta entered conjunction season – a four-week period when both are orbiting more or less opposite Earth but on the other side of the Sun (see image below).

During ‘conjunction season’, the Sun interferes with the direct, line-of-sight radio signals transmitted between Earth and Rosetta.

The yellow line indicates – approximately – the direct line of sight between Earth and Rosetta in February and into March 2015. Radio signals to and from the spacecraft are degraded by the Sun. Via https://sci.esa.int/where_is_rosetta/

“The practical effect is that data rates are reduced,” says Sylvain.

“Now, using ESA’s 35m Estrack stations, we get 14 kilobits per second, and this goes up to 45 kilobits per second when we use NASA’s 70m stations.”

This limitation regulates how much data can be downloaded in any one ground station pass.

By June, the orbital geometry will have improved with the spacecraft much closer to Earth, and data rates via ESA’s Estrack stations will then steadily recover to the maximum rate of 91 kbps.

The 2015 ‘routine’ challenge

The continuing challenge for operations in 2015 is to manage and reconcile all requirements, coordinate between the various specialists that support the mission, book tracking stations for the right times, keep an eye on spacecraft status and health and ensure that the science plan is implemented in the best possible way, while respecting all spacecraft constraints.

“For the flight control team and the supporting specialists at ESOC, like flight dynamics and Estrack stations, the operations workload has gone down significantly compared to the comet approach phase and the landing last year,” says Sylvain.

“Nonetheless, we can’t afford any less attention – it’s still a challenge and will remain so for the rest of the mission.”

Discussion: 15 comments

I really enjoy getting insight into the process on the ground, thank you!

Fasten your seatbelt, it’s going to be an ‘E’ ticket ride!

thanks Daniel,

An excellent overview, it illustrates with enough details this part of the mission to imagine the complex and challenging trade-offs between mission safety, flight dynamics with optical feedback, science objectives, etc.

This makes the mission a thriller to follow-up!!

I wonder if the instrument teams -competing for time allocation- are working in a full collaboration, or if the trade-offs are made by RSGS or by an ad hoc committee, as independent as possible?

During that approximation will ESA try and looking for Philae’s localization?

The flyby was dedicated to science observations; in case you missed it, here is the recent status report on searching for Philae: https://blogs.esa.int/rosetta/2015/01/30/where-is-philae-when-will-it-wake-up/

Thank you very much Daniel and all the Blog team for these informations, especially the ones in “Very short week in, very short week out” section!! Very very interesting.

There must be the answer available somewhere, but I’m still looking for the answer to this question: What is the advantage(s) to chose those series of square-shaped trajectory instead of (rather normal) elliptical one around the comet.

Hi Daniel.

“…workload for mission planning has settled into a more or less predictable, if still challenging, cycle.”

Very grateful to the bridge People. Haven’t heard of the VSTPs before. So, not expecting a lot of ‘live’ info in near weeks. This is the first post talking about the extensive -and full of security procedures- work at ESOC.

Flybys are a bet against destiny. Everyone. Wishing the best.

“The 2015 ‘routine’ challenge: […] and finding Philae 🙂

Why am I not seeing other posts?

The communication Earth to Rosetta is relayed via Mars orbiting transponders when obscured by Sun i was tols a long time ago, you forgot that or has the situation changed?

Rosetta data is not relayed by the Mars orbiters as far as I can see – which do relay data from the robots on Mars.

Although Mars is not in opposition, it is ‘on the other side of’ the sun.’ It’s far from obvious such a relay would be beneficial. That would depend on the relative power, antenna gain, bandwidth etc of the comms systems. They would need to have been designed to be compatible, a non trivial constraint.

There would also be the complication of the *orbit* around Mars to contend with, and conflict with download if data from Mars.

So I don’t think this is correct, unless anyone knows better.

La informacion de ESA es siempre perfecta. Comprensible y muy visual, gracia a todos.

Everybody are wainting for the results and slose up pictures:) I wonder why we don’t see any raw pictures in eg. the next day but alway after four or five? (eg. comet watch,)

Hot off the press! https://blogs.esa.int/rosetta/2015/02/16/cometwatch-14-february-flyby-special/

Only the Navcam pictures are downloaded in near real time; the have to be to be used for navigation. As these images belong to ESAS, they can release them very quickly.

The high resolution OSIRIS data is much bigger, and is stored on Rosetta taking time to be downloaded with all the other science data. The low bit rates at the moment due to Rosetta’s position worsen that. So right now, even the OSIRIS team itself may not have the pictures.

On top of all that we have the whole, much debated issue of the public release of OSIRIS pictures, but there are good technical reasons behind at least some days delay.

Hi Lucas. Also, Due to 67P-Rosetta being kind of in-line with sun, lots of noise, so low bit-rate communications. Using this lapse to present another -not so freshly downloaded- very interesting photos and bits of data 🙂