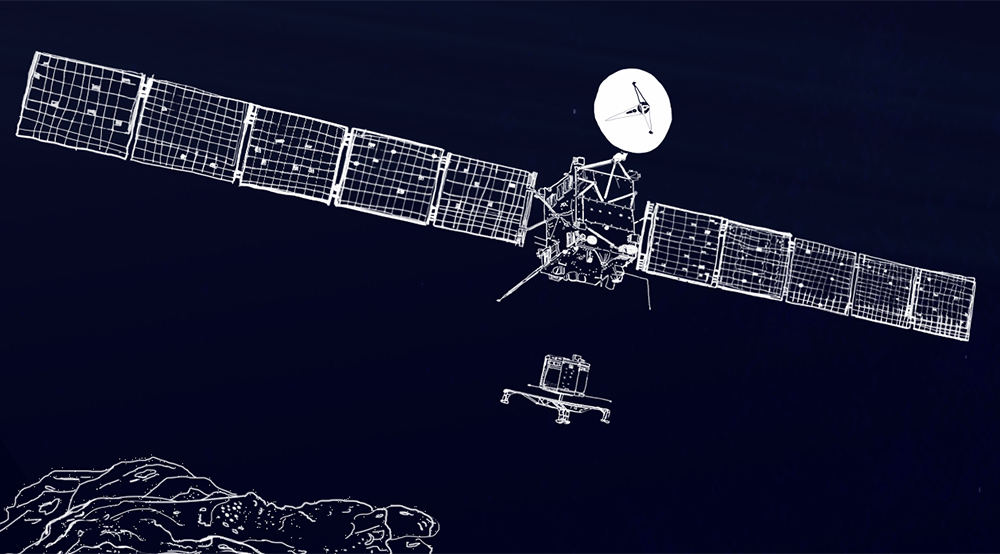

Based on latest images and information provided by the OSIRIS team

The OSIRIS team has been taking advantage of their camera’s high dynamic range in order to gather information from regions of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko that on first impressions appear to be in total darkness.

Quick recap from the OSIRIS team: unlike standard cameras that encode information in 8 bits per pixel and can thus distinguish between 256 shades of grey, OSIRIS is a 16-bit-camera. This means that one image can comprise a range of more than 65000 shades of grey – much more than a standard computer monitor can display. In this way, OSIRIS can see black surfaces darker than coal together with white spots as bright as snow in the same image. (See also our related post: NAVCAM’s shades of grey).

|

|

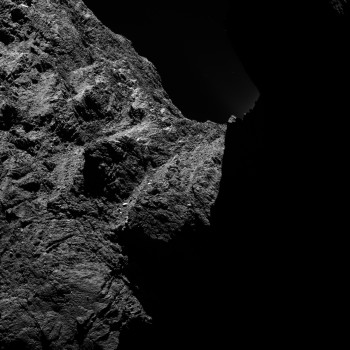

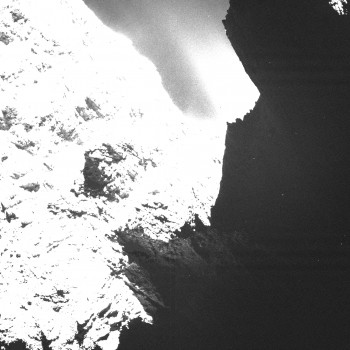

Above: An image of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko obtained on 30 October 2014 by the OSIRIS scientific imaging system from a distance of approximately 30 kilometres and displayed with two different saturation levels. While in the left image the right half is obscured by darkness, in the right image surface structures become visible. The image scale is approximately 0.5 metres/pixel, so the images measure about 1.1 km across. Credits: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/ INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA.

When a region of the comet is imaged in shadow, the light scattered from dust particles in the comet’s coma can offer some illumination, in combination with some adjustment of the saturation levels of the image. The first two images included in this post (above), taken on 30 October by the OSIRIS narrow-angle camera from a distance of approximately 30 kilometres illustrate this technique. They show the same portion of the comet but are displayed with two different saturation levels: while in the first image the right half is obscured by darkness, in the second image surface structures become visible.

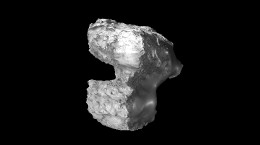

The team also managed to get a glimpse of the as yet unseen southern side of the comet on 29 September, when Rosetta was completing the ‘night-time’ excursion reported on previously. This part of the comet is, at the present time, facing away from the Sun, making it impossible to determine shape and surface structures. This is because the comet’s rotation axis is not perpendicular to its orbital plane but is tilted, and so parts of its surface can at times remain in total darkness – comparable to the weeks of complete darkness in Earth’s polar regions.

A rare glimpse at the dark side of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Light backscattered from dust particles in the comet’s coma reveals a hint of surface structures. This image was taken by OSIRIS, Rosetta’s scientific imaging system, on 29 September 2014 from a distance of approximately 19 kilometres. The image scale is approximately 1.7 metres/pixel, so the frame measures about 3.5 km across.

Credits: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA.

But light backscattered from dust particles in the comet’s coma reveals a hint of surface structures in this mysterious region, although as you can see from the image, much of it still remains in total shadow – for now.

This ‘dark side’ promises to hold the key to a better understanding of the comet’s activity – once the comet draws closer to perihelion next year (perihelion is 13 August 2015, when the comet will be 186 million kilometres from the Sun – roughly between the orbits of Earth and Mars). Then the comet’s southern side will be fully illuminated and subjected to especially high temperatures and radiation. As a result, the OSIRIS scientists believe this side to be shaped most strongly by cometary activity.

In addition, once the details of this side of the comet are known, then parameters such as mass, volume and density can be further refined.

Discussion: 29 comments

I was wondering of it might be possible to see the unilluminated (“dark”) side deatil by “Coma-Light”.

But in the case of the second photo shown today, I don’t think so. The faintly illuminated “darkside” areas seen on the left side are lit by light bouncing off of the parts of the comet still in sunlight and has nothing to do with the light from the coma. I don’t see noise on the really dark side. BUT, it does show greater dynamic range of the camera sensor.

What is the cause of the herring=bone noise pattern in the deeply shadowed areas? Are they consistent enough to be subtracted out?

–Bill

Here is an enhanced 29 Sept 14 OSIRIS montage of Dust Jet activity at a very high phase angle with sunlight forward scattered through the coma. Areas on night side of comet are illuminated by light from the sunlight areas of the comet. Also visible is the ice and dust debris of the coma.

Image Source: ESA/Rosetta/OSIRIS CC: BY-SA IGO 3.0

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo/

https://univ.smugmug.com/Rosetta-Philae-Mission/Rosetta-Dust-Jets/i-dLHz7pf/0/L/ESA_Rosetta_OSIRIS_140929–enh-L.jpg

–Bill

So what are the geographic conventions being used on this topsy-turvy world?

I’ve always assumed that the Polar Plain with the string of boulders and the collimated jets is the NORTH polar area and the other “in winter darkness” pole is the SOUTH polar area.

But I’ve seen little hints that this side we are now examining is really the southern hemi-thing and the darkish side is actually the northern hemi-thingie.

I’m not a geographer, and still use “thatta way” as a valid convention. I need to know what the rest of the world will be using…

🙂

–Bill

The rock outcrop at the bottom right of the picture, looks definatly like it was made by a hot process.

may even have been some of Robs Cryovulcanism.

Does not look like dity ice though, also it two has small craters on it, these craters look unlikely to be from impact, based on the disrtribution arround the shape.

It really looks like it was just extruded out there.

It could of also been a molten rock from an elctrical event that has slid down the slope, presumeably slowly (gravity is low( and landed on the ledge. Hence no splashing or much squashing as it may have been cooling rapidly.

However it was formed it is a truly surprising feature.

Also without seeing a sequence of pictures its not possible to make out if the white specs are dust in mid air or small bright areas on the dark side. Some look elongated suggesting they were moving during time the shutter was open, but not all of them, so another possible interesting feature.

Looks a bit like a huge piece of slag or a big arc weld blobular

Hi Dave. I agree it looks more “extruded” than “erupted”, more like some variety of “pillow lava” being squeezed like toothpaste onto the surface. To think we might have been looking at the boring side of 67P up until now. More craziness to come hopefully.

They should use a flash to light up the darker side – works for me. Just don’t tell me they forgot to pack it…

Fascinating !!

30th of Oct? We were on the 10km orbit at that time – no? You mean 30th of September isn’t it?

Really those high-definition picture are amazing.

Bill, perhaps the only convention here is, ‘Sunny side up’ and ‘Dark side down’, the physics of this Comet defy description as normal conventions do not appear to work on it.

To see boulders sitting there and not defying gravity for a start! Then lots of dust and hard stuff sticking up!

The rotation at some 12 hours is just enough to keep it sitting there.

Clive

Actually at the worst spot, the rotation reduces the downward gravity vector lenght about one third due to the centripetal acceleration. Two third left is still enough to stay put for billions of years,

There is a convention: the North pole of the Earth, as well as every other body in the Solar system (Uranus and retinue excepted) points “north”, that is “above the invariable plane of the Solar System”. and as far as I can determine, the currently sunlit hemi-sphere is designated as North .

Emily covered this earlier:

https://blogs.esa.int/rosetta/2014/10/03/measuring-comet-67pc-g/

–Bill

Thanks for the pics from OSIRIS! Moving in the right direction. Now, still hard to tell visually anything substantial about the comet from this picture. Given that the OSIRIS NAC is able to capture photos with resolutions as high as two centimeters per pixel, any chance you could post one or two of those type pics? Also, since the OSIRIS WAC is designed to study gas emissions, any peep on what it’s discovered? And not to be too demanding, but those of us persuaded by the Electric Universe theory would be pretty keen to know what the RPC instrument array has uncovered as it’s specifically designed to make measurements of the plasma environment around comet 67P, such as:

◾ The physical properties of the cometary nucleus and its surface.

Emphasis will be given to determination of the electrical properties of the crust, its remnant magnetization, surface charging and surface modification due to solar wind interaction, and early detection of cometary activity

◾ The inner coma structure, dynamics, and aeronomy.

Charged particle observation will allow a detailed examination of the aeronomic processes in the coupled dust-neutral gas-plasma environment of the inner coma, its thermodynamics, and structure such as the inner shocks

◾ The development of cometary activity, and the micro- and macroscopic structure of the solar-wind interaction region as well as the formation and development of the cometary tail

https://sci.esa.int/rosetta/35061-instruments/?fbodylongid=1644

What is the reason that no images of the comet are published with a better resolution then 0.5*0.5 meter per pixel? How will you do this with the Philaes camera? It will resolve 0.3*0.3mm per pixel. If this kind of policy remains then we will most likely get no pictures from Philaes cameras and in that case you can read a lot of complaints in this blog. And by the way my monitor has a better dynamic range then 12 bit per color and with image processing this means that it is almost possible to visualize the full dynamic range of the Osiris cameras 16 bit. My phase-one has 18 bit compressed to 16 bit and is even a bit better then the Osiris, i use it a lot. The normal cameras in phones and web toys have 8 to 12 bit resolution and all those megapixels promised are just about worthless as the dynamic range of a camera is more important than the pixel numbers once above 2 megapixels as this is the limit of the monitors in general.

I have had similar thoughts about the Philae images to be presented here: a single pixel? Bet it will be black.

Wow! These OSIRIS images are really pretty ones. Thank you Emily. Happy scientists from the OSIRIS team, that are dealing with such images every day from about two months….

I am puzzled. Where is the light scattered by the coma on this image? It looks to me like all the visible features come from reflection off the surface of Chury-Gera…

Is it time for me to purchase a new screen for my computer?

I mean: where are the surfaces lightened by the coma. Of course, jets are visible…

I have a name for that irregular cave: “il grotto” (what will that be in egyptian?)

Well its nice to see some OSIRIS images, thanks Emily, but old Holger is still not giving much away. The single image is so stretched contrast wise any detail on the sunlit side is whited out and the details in the shadow are hard to distinguish from the “hessian”. However it does give a hint of what lies round the corner from the images of the neck area where we saw the dunes. The single big boulder in the middle of Landing Site A (The “Amphitheatre”) is visible as a grey spot in amongst all the white. The material dripping over the edge on the right sure does look to have been molten at some time in the past.

The 30th October Image A, is the sort of image we like to see from the OSIRIS team. We have little idea of where this is on the comet and no idea how it relates to the other close up NAVCAM images, that aside it is truly a revelation. The surface of the comet as it really is when not covered with “Reglisse” (Thanks Thomas, see 4/11 blog page). Numerous little pits and indentations, scars, fractures, bumps and crevices. Even Gnarly doesn’t do it justice. The old lady is in serious need of some botox and shedloads of vanishing cream.

Utterly alien, so “weathered” looking, but no wind or rain to do the eroding. It still looks like rock of some sort, but totally unlike any rock I have seen pictures of. Especially when you zoom in a bit and see all the little plumes of gas as seen in the NAVCAM images. That little bit of extra resolution helps a bit, but as Cometstalker says why not just show us the real detail so we don’t have to squint, guess and debate? One might begin to think Holger and his team get some sort of entertainment from teasing us this way.

ESA has decided to delay the release of the OSIRIS results for 6 month.

The reason is to protect the advantage of being first to publicise

new scientific findings

Well there is a certain rationale supporting such a policy I admit.

I personally support a different handling – anyway.

The question now is how will ESA handle the Philae images.

Since the image resolution is expected to be way higher than OSIRIS

Will we have to expect the Philae images SIX MONTH LATER ?

That implies we will see Philae images in May or June 2015

For me, the top priority is no longer the OSIRIS images but the VIRTIS images in the infrared spectrum. They were designed to highlight local differences in temperature, for example that of those much whiter hot-spots, hot patches and hot ridges seen everywhere on the comet’s surface (and not just in the neck region). VIRTIS principal investigator Fabrizio Capaccioni said back on August 1 that “very soon, VIRTIS will be able to start generating maps showing the temperature of individual features”. He is apparently still keeping those maps up his sleeve.

Why? Too hot to handle?

You’re welcome, Robin, thanks for the credit.

Personally, I still prefer the plain English term “liquorice “” (or the American term “licorice”), which is immediately understood by a vast majority of visitors to this blog.

It is totally evocative of the sticky nature of the comet’s black surface-plains which you hypothesize and which I find hard to swallow. I still believe those plains are more akin to rock-hard lava than to liquorice.

“In addition, once the details of this side of the comet are known, then parameters such as mass, volume and density can be further refined.”

I need an explanation to how the mass of the comet can be refined by the image information of “this side”. I see no way to put this parameter into the Keppler algo.

Please enlighten me, i am still able to learn something new..

( that volume and density figures might change i agree)

I think it might be more about Mass distribution rather than the entire mass of the comet as all the orbital manoeuvres to date seem to have gone OK so far, or just adding a couple of decimal places to the scant 1 x 10^13. The Volume is a very approximate value calculated using boxes. Once they have a complete 3D shape model they should be able to give a far more accurate Volume and Density.

I think the mass distribution is best made by analyzing the trajectory of the orbiter at its 10 km average distance in the past. The additional image information then adds to the accuracy of the comets shape and this again can be used to calculate the density distribution.

Possibly the info from Em was a giveaway that the comet is not uniform in its density profile, if so this leaves room for a lot of speculations. Say that the main body has a density of 0.3g/cm3 and the head has 1g/cm3 and the neck is a mix of both, this would be fun and everyone can be pleased to find a snowy dirt-ball and a dirty snowball.

About the resolutions, calm down. I’m sure your monitors and cameras might be better but this thing was launched over 10 years ago and was developed and constructed over several years before that. It’s amazing these pictures are even the quality they are. I’m sure in time we will get the larger versions.

A four megapixel 16 bit dynamic range camera with a very good mirror telescope and the filter set ranging from UV to NIR is the same today as when launched a decade ago and still is the state of art for an interplanetary camera that is supposed to have a lifespan outranging the mission time scedule with good margin. The images are not crippled due to old technology as the osiris is just fine as it is. The poor image quality that is presented is due to manipulation that is made TODAY. I hope i made this point clear.

COMETSTALKER – the entire OSIRIS & ESA/Rosetta/Blog is recorded in ultra high grade resolution and will show up as a documentation afterwards

(watch for the moderation-blitz that is automatically applied to my comments.) Nice – hey?

the anomolous images are baffling – this is incredible. It seems like this conjoined object is some sort of craft, maybe not currently occupied but was before…