Guest post by Sebastien Besse, Research Fellow at ESTEC

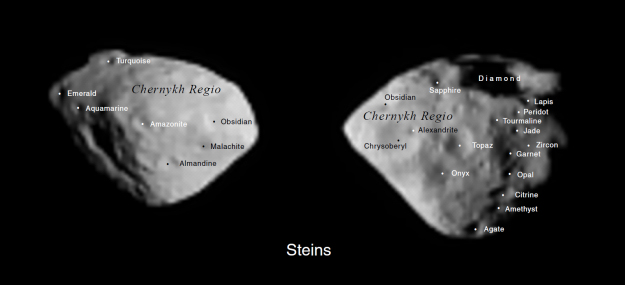

On 5 September 2008, ESA’s Rosetta comet chaser completed its first encounter with a main belt asteroid when it flew past Steins, which revealed itself as a diamond-shaped object with dimensions of 6.67 × 5.81 × 4.47 km.

At the time, I was a PhD student working with the OSIRIS imaging team in France studying the craters on Steins. With the asteroid’s diamond shape for inspiration, I began to think about naming the craters after different gemstones. I tried to select names that would be familiar or appealing to the general public, and easy to pronounce.

Asteroid Steins feature names

Credit: ESA/ 2012 MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/RSSD/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA

As is the case with the official place names given to all worlds in the Solar System, they have to be approved by the International Astronomical Union (IAU). We had quite some discussions because we had to choose names of gems or precious minerals/stones that would not be confusing for studying the true mineralogy of the asteroid’s surface. In the end, the OSIRIS imaging team agreed that the names of 23 gemstones or precious minerals would be recommended to the IAU.

To date, about 40 craters have been identified on Steins, but only the most prominent of them have been given names. In some cases we tried to name craters geographically close to each other with names from the same gemstone family. So for example, Aquamarine and Emerald are both from the Beryl family of gemstones, and Agate, Amethyst and Citrine are all types of quartz. Another example is that the crater Alexandrite sits inside the crater named Chrysoberyl – I named them like this because Alexandrite is a type of Chrysoberyl.

Asteroid Steins seen from a distance of 800 km, taken by the OSIRIS imaging system from two different perspectives during the flyby.

Credits: ESA 2008 MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/RSSD/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA

The most obvious crater is an impact feature near the south pole (top in the images) – now known as Diamond crater – which measures 2.1 km in diameter and is 300 m deep. The relatively large size and depth of this crater compared with the asteroid itself indicates that Steins was probably shattered by the force of the collision, meaning much of its interior resembles a rubble pile rather than solid rock.

A circular crater 650 m wide and 80 m deep named Topaz sits in the centre of the asteroid. Topaz is the easiest feature to see in this region and so is used to mark the asteroid’s centre of longitude.

Another noticeable feature is the chain of craters that stretches from the asteroid’s north pole (the pointed area at the bottom of the images) all the way to Diamond crater. This feature may be linked to the shattering impact that created Diamond crater at the south pole. At least some of the craters in the chain may have been formed by loose material sinking into a subsurface fracture. Several of these craters are named after familiar gemstones such as Opal and Jade. I included Citrine, since it sounds like the French word for lemon: citron.

As a geologist it feels good to have promoted the names of these gemstones out in space! But as is the case with the naming of geological features on any world, it also provides a solid framework for discussions about certain features. Rather than having to say “you know that crater next to the funny shaped one…”, we can refer to named features, which makes discussions and writing papers a lot easier!

Read more in Sebastien’s paper Identification and physical properties of craters on Asteroid (2867) Steins.

Discussion: 7 comments

This is a nice article. However, there is one problem with the names shown on the images. The crater Obsidian, shown on both images, is actually given to two different craters. I have posted a global map of Steins here:

https://www.unmannedspaceflight.com/index.php?showtopic=5256&st=300&gopid=212681&#entry212681

On the map I only label one of the two Obsidian craters – the other is faintly seen below it and to the left (SSW) – or SE of Chrysoberyl. On the labelled image in the story, the crater without a name situated right at the ‘point’ left of Chrysoberyl in the right-hand image is the ‘Obsidian’ from the left-hand image. Note my map has south at the bottom, the images have south at the top.

Read an interesting remark about the naming of craters on asteroid (2867) Šteins on the ICA CPC blog.

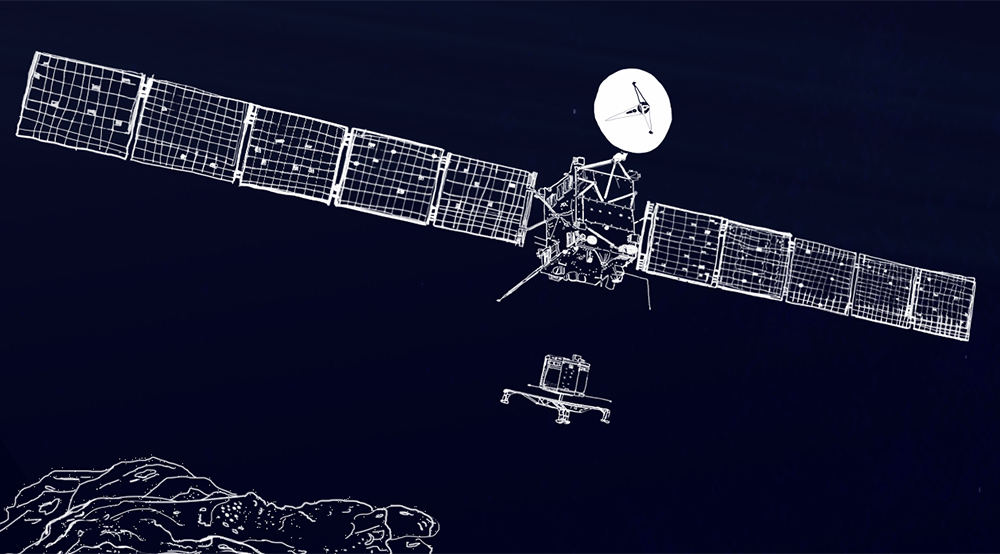

The Naming of Names is always an important task in planetary exploration. Even though we have been at Comet 67P/C-G a short while, I have adopted p’haps a dozen informal names for features while awaiting the IAU names. And since they are in-house and informal, they can be somewhat whimsical. 😉

–Bill

I tried finding OSIRIS images of this asteroid at ftp://psa.esac.esa.int/pub/mirror/INTERNATIONAL-ROSETTA-MISSION/OSINAC/ but unsuccessfully. Could anyone please link those images? Thanks.

Never mind that, found some images and made this RGB composite (hopefully true-colour): https://www.pictureshack.us/images/72978_rosetta-steins-rgb.jpg

That ‘interesting comment’ about the use of English rather than Latin names on Steins is incorrect. Crater names are not required to be latinized – mountains (Mons, Montes), velleys (Vallis, Valles), and so on are – the descriptive part of the name anyway. Crater names are most often of people, sometimes other things, but usually today given in their own language. I might agree that IAU should have been more inclusive as a matter of diplomacy, but this is not incorrect.

This is a very nice article, but there is one problem with Obsidian image, shown on the both images.