Last week I spoke to students from three universities in Italy, Germany and Israel. I liked their questions a lot because they allowed me to be playful in my answers, I tried to get them to leave with more questions that their young minds can investigate further.

[youtube VsbpgzofaWw]

One deceptively simple question came from a girl who asked me: “What impresses you most about the Space Station?”. She was not referring to my mission, nor to my view of Earth that over the past 150 or so days has reshaped my mind’s geography but she asked about the Station itself. I had never asked myself this question because an orbiting space station is such an extraordinary concept that I find the idea alone impressive. But this was not the right time for me to beat about the bush and, in a few short moments that felt like a long time, I pictured the Space Station and asked myself the same question. What sprang to mind were the moments after opening the hatch of the Soyuz TMA-09M as I entered human’s frontier in the cosmos for the first time. Among the thousands of thoughts that crowded my mind nearly six months ago, one thought in particular stood out and I replied: “Its dimensions …”. Today I would like to welcome you on board the station, and take you through its modules, starting from its tail end…

Automated Transfer Vehicle 4 (ATV-4)

Quiet and dark, Albert Einstein is a awaiting to depart. To light the spacecraft, you send a command through a computer that controls the on-board systems – in this case with the Russian ones. The four fluorescent lamps, identical to those on the American, European and Japanese segments, give out a very dim light when first turned on before they start gaining power and emit enough light to move freely. We are inside a closed cylinder with a curved surface. Outside the pressurised volume in which we find ourselves lie the spacecraft’s systems along with the pressurised liquids and gas. Beyond those you will find ATV Albert Einstein’s engines. On either side are two valve systems that let water, air and oxygen into the Station. Two racks bays on each wall surround us, above (overhead), under (deck), left (port) and right (starboard), eight in total. The racks are container shelves on which we have placed an enormous amount of waste, practically equal, in volume and weight, to the supplies ATV-4 brought us four months ago. In front of us a cone-shape narrows into the docking system, which ingeniously doubles as the access hatch to the Russian segment. When we leave the module, we close the hatch for the last time: tomorrow ATV-4 will undock from the Station but we will see Albert one more time from above when it disintegrates as it re-enters the atmosphere.

Service Module

Once through the narrow ATV hatch we find ourselves in a small compartment shaped like a sphere and filled with containers. We use this area as a closet, but is mainly a corridor to access the Zvezda’s operating compartment (Zvezda means star in Russian). This is the central module of the Russian segment where Russian cosmonauts spend most part of their days in orbit.

Immediately to our left is a small compartment: the bathroom. A suction fan that creates an air flow to direct waste away. Solid waste goes to an airtight container, liquid waste goes through a separate tube similar to a vacuum cleaner for recycling separately. The space is really cramped, but the system works well and does not generate unpleasant odours, the space is simple but functional. Moving towards the bow of the Space Station, still inside the Service Module, we find two crew quarters left and right where Fyodor and Sergey sleep. The size of the crew quarters are no bigger than a phone booth. They are similar to those in Node2 where the rest of the crew sleeps, but they have a feature that makes them particularly luxurious: a window to the outside!

The lining of the walls, an opaque cream colour carpet, allows you to fix anything directly onto them thanks to the ubiquitous Velcro. There are only very few panels on the station that are not covered by Velcro.

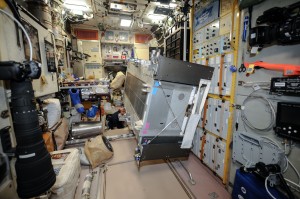

Continuing our journey forward a folding table can be seen where generations of space explorers have dined together. The table includes an element to warm up meals. On the right there is the water dispenser that delivers water hot and at room temperature. On the left there is another water dispenser for long-duration stays . Next to the table, towards the Station’s bow, you will find the system to regenerate our atmosphere. This large apparatus is constantly in motion with the sound of the a clock pendulum in motion. Moving on the space narrows on both sides and we find our cameras and lenses, sorted by focal length from wide-angle to 600mm zoom. The deck in this area contains a number of windows with excellent optical properties. To watch the planet go past underneath us is an endless source of entertainment. Two computers with access to the onboard analogue system are located on the sides of the central panel. There are three computers: one to access the Russian systems, one for the American systems and one for the onboard network. The ATV control panel, through which I followed the spacecraft’s docking and I will monitor its undocking, is installed on the right side. Usually TORU, the manual command system for Progress, is here as well.

We go through another hatch to get into another round compartment , larger and more comfortable than the previous one. This compartment is different from the first one because it is a node with three docking points to which three modules are docked.

Mini Research Module 2

As we float towards the zenith, we enter the Mini Research Module 2. With its elongated bell shape, this module is used as a docking port for logistics modules and for the of Soyuz A line (used for Expeditions with uneven numbers for example now the Expedition 37/38 Soyuz is here). The walls are covered with the same cream-colour carpet but they are newer here and the colour is more vivid. This module has two hatches on the outside, one positioned towards the direction of flight, the other in the opposite direction . Each door has an integrated window. At the zenith we find the Soyuz spacecraft, dark and silent, apart from the never-ending sound of the fans. If we settle into the Soyuz’ descent module we are at the highest point of the Station: there is no human presence above us.

Docking Compartment 1

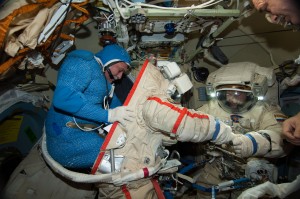

Russian cosmonauts Fyodor Yurchikhin (left) and Alexander Misurkin in the Docking Compartment. Credit: NASA

Going in the opposite direction, towards the nadir, we enter the Docking Compartment1. This compartment, identical to the MRM2, is used as a docking port for the Russian Progress cargo vehicle and as an airlock for Russian spacewalks. The two Orlan spacesuits always stowed here and Oleg and Sergey the activation procedures for the two suits some time ago. At the lowest point we can see the Progress shuttle that docked to the Station a few months ago and since emptied. The spacecraft is gradually being filled with waste until it departs.

Logistic Module – Zarya – FGB

Zarya which means dawn in Russian is the oldest Station module, launched in 1998. Although it holds various systems used during autonomous flight, it is now used for storage. The walls are panels that can be easily opened to access the equipment in storage. Crossing towards the front of the Station, the deck is completely covered by cargo , secured by elastic cords and Velcro. The cargo covers about a third of the walls. If I stretched out straight, the material would come up to my knees. At the front, the module is completely empty: here Fyodor, Oleg and Sergey wash in the morning and after exercise, and three of the walls are covered by their personal items. The best way to quickly cross this module is to use the bars on the walls: they almost look like horizontal boxes. Sometimes coming from the Service Module I have fun crossing FGB with my feet forward , forcing my brain to think vertically: the feeling is similar to descending into a well.

At the very front we go through another hatch and find ourselves in another rounded compartment, as large as the one on the other end but with two docking points .

Mini Research Module 1

Descending towards the nadir we enter the Mini Research Module 1. It is bigger than Mini Research Module 2 and the Docking Compartment 1. The interior has a square cross-section, and just like the FGB the walls are covered with panels that can be opened to access the equipment stored behind them. The lowest part of the module holds the docking port for the Soyuz line B for Expeditions that start with an even number such as 36/37. My Soyuz is docked there at a 45 degree angle compared to the direction of flight. But not for long in preparation for the arrival of TMA-11M, my crew will undock from Mini Research Module 1, fly around the International Space Station to reposition the vehicle behind the Service Module, and then dock in manual mode. This manoeuvre is rarely done but I am trained for it together with Fyodor and we are pleased to be able to perform it.

END OF PART ONE

Discussion: 25 comments

Grazie Maggiore,

è bello poter vedere la ISS attraverso i tuoi occhi.

Dopo questa tua missione nulla sarà più lo stesso… grazie di aver condiviso con tutti noi questa splendida avventura.

Ciao amico tra le stelle ^_^

Il nostro Cicerone… no, preferisco: il padrone di casa, che, amorevolmente, ci accompagna per le stanze della sua dimora. 😉

Questo è proprio periodo di tour, eh? ahahah Prima il video, adesso con le parole.

Sai qual è la cosa bella? Che questi “visitatori occasionali” la considerano un po’ anche casa loro. L’abbiamo girata così tanto in questi mesi che un po’ di familiarità l’abbiamo acquisita. Certo, alcuni nomi non li ricordo, e non li ricorderò mai. Però saprei muovermi abbastanza bene.

Che bella descrizione dettagliata che hai fatto… 🙂 mi son ritrovata lì, forse ancora di più che guardano il video dell’altro giorno. Io lo dico che con te siamo stati dei privilegiati, anche noi. Sembra tutto così semplice… da quando lassù abbiamo due occhi ed un grande cuore che ha condiviso tutto questo con noi, facendocelo toccare con mano. Grazie.

Fine commento della prima parte. 😀

PS: Lo spostamento della Soyuz sarà una bella novità per tutti.

Se arrivo per l’ 11 novembre ci prendiamo un un caffettino nel SM?

Grazie Luca, davvero. Mi sembra di stare lassù, come sognavo quando ero piccola…!

Abbracci virtuali

Iole

Sarebbe bello poter anche per solo 1 minuto stare li su con voi nella ISS, spero che un giorno lo spazio sia accessibile a tutti e non solo agli addetti ai lavori e ai facoltosi ricchi che hanno potuto fare i turisti spaziali. Il cosmo è la chiave della nostra vita !

Grazie infinite come infinite sono le stelle…..!!!

Buon proseguimento della missione Maggiore….!!!

Grande come un campo da calcio …….sì perchè per circa 6 mesi abbiamo viaggiato un pò anche noi con voi!

E questo è straordinario.

Maggiore,

attraverso lei si realizza il mio sogno da bambino del volo spaziale.

Grazie

Grazie Luca per averci accompagnati in quella che da circa sei mesi è la tua dimora.Ce l’hai illustrata così bene che mi sembra di averla visitata anch’io .

Mi è piaciuto il tour,mi è mancata un pò l’aria però mi sono divertita,grazie maggiore.

Quando la mia piccola nipotina Melissa sarà abbastanza grande,le racconterò di “quel ragazzo della porta accanto”,che gentilmente ci ha fatto conoscere emozioni nuove,

viaggiare su un’ astronave spaziale, e vedere la terra in un’altra prospettiva,le farò vedere le foto e i nostri occhi brilleranno per le tante bellezze.

Grazie Maggiore, vedere queste foto, leggere i commenti con un linguaggio semplice e chiaro e’ estremamente piacevole, viene voglia di farci un giretto sulla ISS …

Grazieeeeeeeeeee!!!! di condividere con noi tutto questo mondo fantastico! il video è stato un bel regalo dopo le tue foto…e questo è la ciliegina sulla torta come le stelle per la luna 🙂

Un fantastico tour della casetta spaziale e tu da perfetto padrone di casa ci hai illustrato molto e bene la sua funzionalità. Certo i nomi della stanze per me saranno un po’ difficile da ricordare, ma è stata una visita molto interessante ed istruttiva. Quante cose ho imparato da te in questi mesi, quanti posti mi hai fatto visitare e visti con un visuale che mai avrei potuto godere. Fantastico, fantastico Luca, continua ancora il tuo viaggio ancora per questi giorni e noi conserveremo nel cuore i tuoi regali. Buon Viaggio maggiore!!

Ogni volta, ogni giorno, ogni minuto…noi ci meravigliamo di più grazie a te.

Grazie Luca.

ho fatto un gran bel viaggio eh… quasi quasi lo ri-leggo… così ri-torno!

Ciao Luca,

evito di essere ripetitiva dicendo quanto sono interessanti questi tuoi articoli 🙂

Più che altro scrivo questo commento per darti un suggerimento. Sarebbe bello se, alla fine della tua missione, raccogliessi tutti questi articoli in un ebook, scaricabile gratuitamente qui dal tuo blog, per permettere a noi appassionati di poterli rileggere con attenzione, proprio come un libro. Tra l’altro credo che sarebbe molto utile a scopo didattico.

Pensaci!

Buona permanenza e buon lavoro!

Carla

Grazie Astro Luca!

Questi sei mesi sono stati fantastici, ogni tanto ti vedevo sfrecciare sui cieli lassu’ vegliando su di noi! Ed e’ davvero bello leggere tweet e blog, ormai un appuntamento fisso!

Penso che se ognuno di noi potesse vedere la Terra anche solo un minuto da lassu’, il mondo sarebbe migliore e avremmo tutti piu’ cura del pianeta e piu’ rispetto per ogni essere vivente. Grazie per avercelo fatto capire con le tue foto e i tuoi racconti.

Quando tornerai, mi manchera’ Astro Luca!! Pero’ il vero paradiso e’ il nostro pianeta quindi fate buon rientro!!

Saluti

Irene

Leggerti è meraviglioso come credo sei tu… grazie super Luca. Un abbraccio.

Fantastico!! Gli scenari descritti dagli scrittori di fantascienza, e che hanno nutrito il mio spirito con le letture di moltissimi anni, sono diventati con voi cose “normali”, “banali”, “quotidiane”. E la meraviglia è immensa. Ma come, siamo già nel futuro?

Passeggiate spaziali, astronavi, tute pressurizzate, capriole in assenza di gravità, oggetti che galleggiano. Tutto normale e quotidiano…

Una domanda: tra i membri dell’equipaggio c’è sicuramente un forte affiatamento ed una profonda amicizia. Capita invece a volte che ci siano problemi di relazioni umane?

Grazie

E’ stato bellissimo poter “vedere” l’ISS attraverso i tuoi occhi… Solo un uomo straordinario come te poteva renderci partecipi di tutto questo. Sono certo che anche la seconda parte sarà altrettanto emozionante.

Luca, sono stati 6 mesi bellissimi… E’ stata un’esperienza straordinariamente Spaziale.

Grazie di tutto, caro amico!

Nessuna storia può vivere se non viene descritta e se non c’è qualcuno a leggerla e ad ascoltarla… quindi grazie Luca , tutte queste “poesie” resteranno con noi sempre… anche dopo il tuo ritorno a “Casa” , e ancora , ancora … 😉

Un abbraccio Samantha

Hello Luca,

I am so glad to be able to communicate. It is funny but few times I saw myself in a my dream, during my sleep that I am on spaceship and see the Earth from a side, with it

size of a small apple. I got scared from realizing that I am a far away from the Earth, but physically I felt absolutely OK, and I had No space “suite”. I just wondering, that’s probably is OK to be in this distance from the Earth for human body?

Thank you from Los Angeles,

Olesa.

Una cosa non viene mai detta dagli astronauti quando arrivano per la prima volta nella ISS: che odore ha? Ogni volta che entriamo in un ambiente nuovo, sia una macchina o la casa di amici, percepiamo un odore diverso dal quale siamo abituati. Quando apriamo il frigorifero, che sia vuoto o pieno, ha un odore nettamente diverso dal resto della casa. Nella, stazione spaziale quale è? E cambia col tempo, nel senso che cibi o altre attività possono altararlo finché i filtri non li ripristinano? In altre parole, quali sono gli odori, o le puzze, durante una missione sulla stazione spaziale?

Luca, che fatica scrivere questo post.

Forse perchè rischio di ripetermi, forse perchè le parole più belle le hanno dette gli altri, forse perchè penso che siano gli ultimi post che mi accompagneranno in questa avventura…

Era giugno quando è iniziata per me, ma come molti non avevo abbastanza coraggio per scriverle, l’osservavo, la leggevo, guardavo ammirata ogni parola che scriveva…

Poi, con il passare dei giorni assimilavo notizie, e prendevo coraggio…

Oggi con lo stesso coraggio le scrivo ed è un’ emozione sempre molto forte…

Le vorrei lasciare a proposito di coraggio queste parole tratte dal libro “Il Guerriero della Luce”:

“Un guerriero della luce non ha mai fretta.

Il tempo lavora a suo favore: egli impara a dominare l’impazienza, ed evita gesti avventati.

Procedendo lentamente, nota la saldezza dei propri passi.

E’ consapevole di essere partecipe di un momento

decisivo della storia dell’umanita’, e sa che, prima di trasformare il mondo, deve conoscere se stesso.”

A presto.

Hi Luca,

That was a very informative tour. You could also do a video like the one Chris Cassidy did touring the ISS. Speaking of your buddy Chris Cassidy, he was interviewed on NASA TV Space Station Live. I saw the replay today (November 2, 2013). He looks great. He said he did not have any tingling in his feet and legs and came back feeling great and healthy. He said it was because of the exercise machines on the ISS. It was great to hear that he feels super. So, keep exercising! So you and Fyodor and Karen will be coming back soon. Can you believe it? Time goes so fast! Try to stay away from the germs when you get back to earth. They are making the rounds. I caught it at work. I was not sure I was going to live through it. (strep throat + laryngitis + chest congestion + sinus infection). Got a second opinion and antibiotics and because of that, I am on the mend. As always, Godspeed.

HEI, LASSÙ ! Un saluto da quaggiù 🙂

È stato un onore aver incrociato la mia orbita con la tua.

Mi hai insegnato tanto.

Mi hai fatto riscoprire il cielo, ed il piacere di perdermi nell’immensità del firmamento.

Mi hai fatto riscoprire la Terra, e le sue forme strane e bizzare, che sembrano quasi le tracce dell’anima del mondo.

Hai fatto volare in alto la mia fantasia, che si espressa attraverso storie e racconti su mondi possibili e differenti.

Ma soprattutto mi hai trasmesso il tuo sorriso: quel sole luminoso che contagia chiunque ne venga a contatto, e lo sprona a scoprire le cose belle del reale con aria scanzonata ed essenziale.

Per tutto questo, ed altro ancora … GRAZIE.

Torna dai tuoi cari AstroLuca, vai e conquista il mondo con la tua voglia di metterti sempre in gioco divertendoti.

E, in qualsiasi modo, dai segnali di te, e facci giungere il tuo pensiero.

Pure attraverso un cartellone di pubblicità 🙂

Chissà, forse un giorno ti ricorderai di un folletto, con la foto di una bimba per profilo, chiacchierona ed esuberante, che su fb ti parlava in catanese, e ti seguiva con entusiastico affetto.

HEI LASSÙ ! Buona vita Luca, e in bocca al lupo per il ritorno quaggiù.

Con immensa stima, Valeria