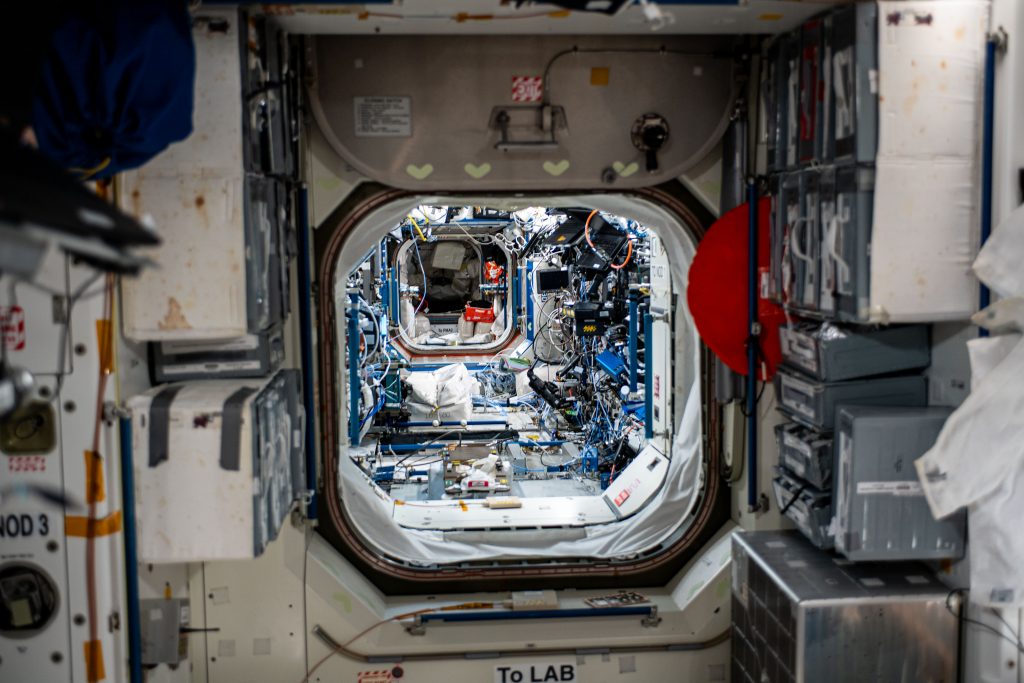

The International Space Station is the astronauts’ home and office, about the size of a six-bedroom house. Up there, no windows can be opened and most of the work is carried under artificial light. Working in space means being confined to a remote and isolated environment for long periods of time.

Right now, there are 11 people living together in orbit. ESA project astronaut Marcus Wandt is among them, and he will be the first one to run an experiment that investigates how people’s physical and psychological well-being can be affected by living on the Space Station.

Expedition 70 and Axiom Mission 3 crews on the International Space Station. Credits: NASA/J. Moghbeli

Less stress, better performance

The Orbital Architecture study explores how the design of space habitats affects the astronaut’s stress levels and mental agility.

Researchers will monitor a whole range of parameters to see how Marcus copes with the new environment, including his heart rate, brain activity, sleep quality, diet and exercise routine.

Marcus trying a cap with sensors to record his brain activity during training at the European Astronaut Centre in Cologne, Germany. Credits: ESA

The Swedish astronaut will carry out tasks on a computer while wearing a cap embedded with sensors to monitor his brain activity. The tests will record his working memory, reaction time, attention, and organisation skills. Marcus will run these sessions in different locations almost every day of his two-week stay in orbit.

“By understanding how architecture influences astronauts, we can create spaces that support their thinking and emotions for mission success. We can reduce stress and increase their cognitive performance,” says Michail Magkos, one of the co-investigators of the study supported by the Swedish National Space Agency.

Architecture for extreme environments

The team have run this experiment in a simulated martian mission last year with other seven volunteers at the Mars Desert Research Station, and is planning to have more test subjects to compare results.

“This is the first time for Marcus and us in space. We are very happy to see how involved and curious he is with our study,” explains Michail.

As space agencies plan for longer space missions to further destinations and with more diverse crews, creating habitats that help them think clearly and handle stress is key.

“The dream we are working towards to is making future space designs more accommodating. We want to take into account mobility, privacy and views to the outside world. New space stations could look more like a kids’ playground with handles placed as a spider web to move around in microgravity,” says Michail.

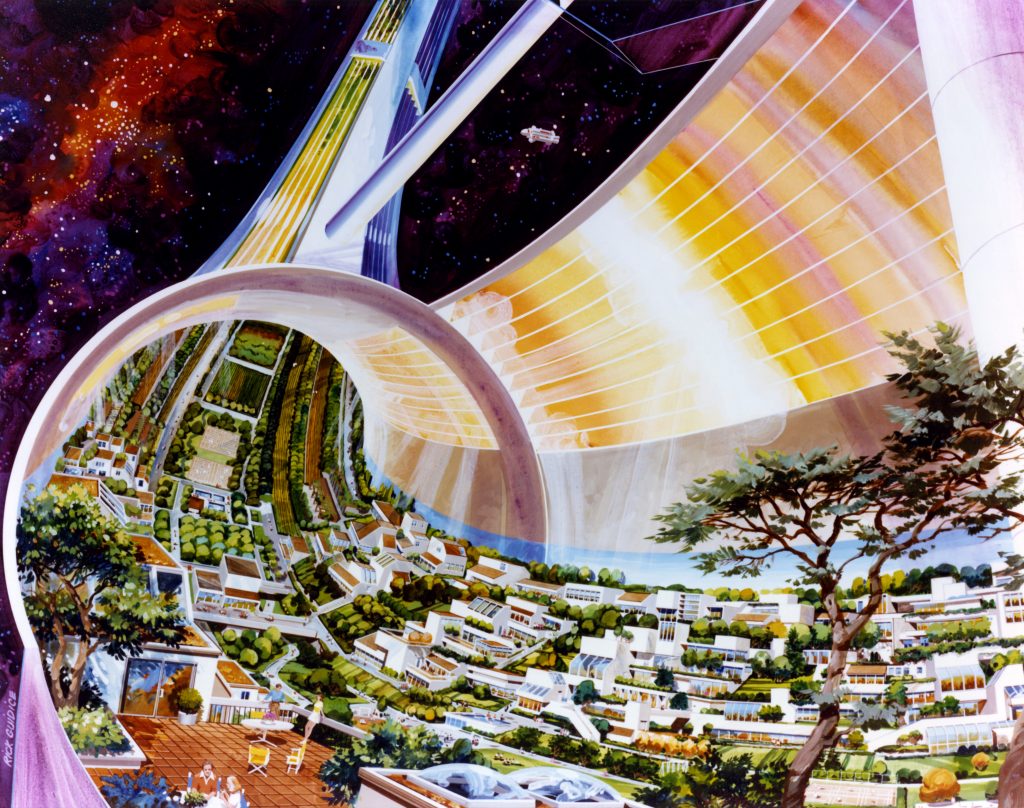

The idea of designing space habitats is nothing new. In 1975, a NASA study designed the Stanford Torus, a doughnut-shaped ring in orbit capable of housing an entire city with thousands of people living in artificial gravity. The space colony was an experimental exercise in the infancy of human space exploration.

Researchers hope to learn what works best in space, and apply the lessons learned to extreme environments on Earth, such as submarines, Arctic research stations and offshore platforms.

For now, it is time for rigorous data collection both in space and on Earth.