From human waste to superplasticiser, astronaut urine could become a useful resource for making a robust type of concrete on the Moon.

A recent European study sponsored by ESA showed that urea, the main organic compound found in our urine, would make the mixture for lunar concrete more malleable before hardening into a final, sturdy shape for future lunar habitats.

Researchers found that adding urea to the lunar geopolymer mixture, a construction material similar to concrete, worked better than other common plasticisers, such as naphthalene or polycarboxylate to reduce the need for water.

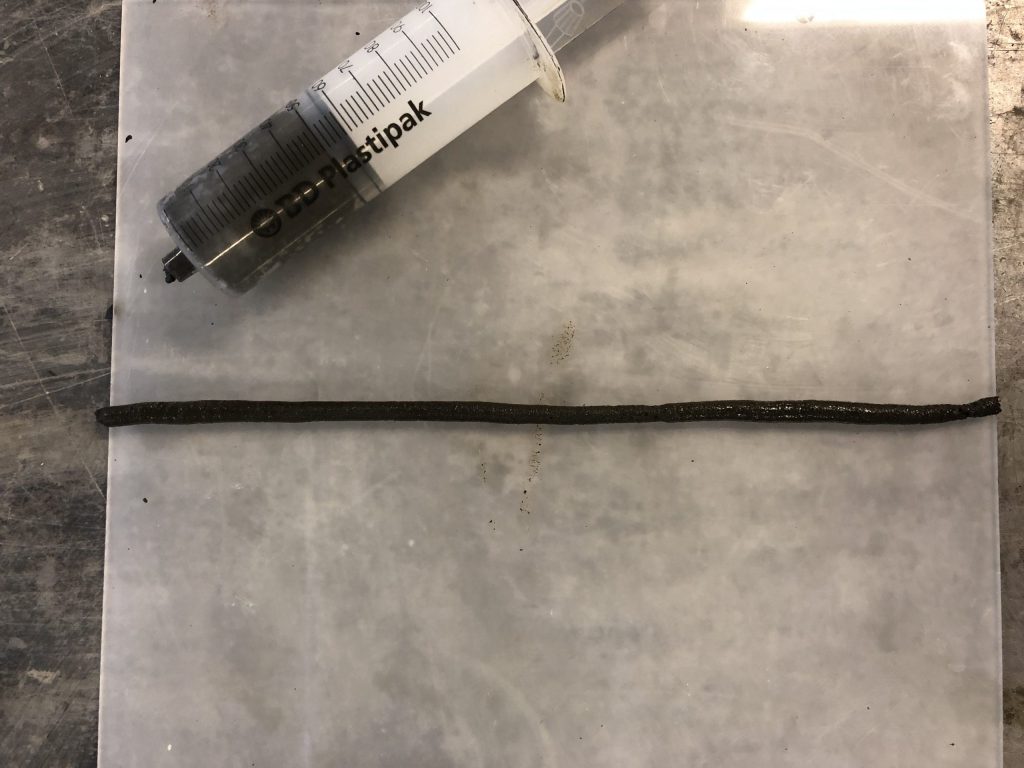

The mix coming out of a 3D printer proved to be stronger and retained a good workability – a fresh sample could be easily moulded and retained its shape with weights up to 10 times its own on top of it.

“The science community is particularly impressed by the high strength of this new recipe compared to other materials, but also attracted by the fact that we could use what’s already on the Moon,” says Marlies Arnhof, initiator and co-author of the study from ESA’s Advanced Concepts Team.

Using only materials available on site – an approach known in the space arena as In-Situ Resource Utilisation, or ISRU – will reduce the need of launching huge volumes of supplies from Earth to build on the Moon.

The main ingredient would be a powdery soil found everywhere on the surface of the Moon, known as lunar regolith. The superplasticiser urea limits the amount of water necessary in the recipe.

Thanks to future lunar inhabitants, the 1.5 litres of liquid waste a person generates each day could become a promising by-product for space exploration.

“Urea is cheap and readily available, but also helps making strong construction material for a Moon base,” points out Marlies.

Why urea?

After water, urea is the most abundant component of human urine. Urea can break hydrogen bonds and reduce the viscosities of fluid mixtures. Urine also contains calcium minerals that help the curing process.

On Earth, urea is produced on an industrial scale and widely used as an industrial fertiliser and a raw material by chemical and medical companies.

“The hope is that astronaut urine could be essentially used as it is on a future lunar base, with minor adjustments to the water content. This is very practical, and avoids the need to further complicate the sophisticated water recycling systems in space,” explains Marlies.

Bring it into the mix

Several tests confirmed that this type of concrete mixed with urea was capable of withstanding harsh space conditions such as vacuum and extreme temperatures. These two factors have the biggest effect on the physical and mechanical properties of construction material for the lunar surface.

All samples were subjected to vacuum and freeze-thaw cycles to simulate the sharp temperature changes throughout lunar days and nights, which might vary from -171°C to 114°C.

The samples withstood temperatures ranging from 114°C to -80°C as a good indication of how the material would behave under even lower temperatures.

Community building

A close collaboration between ESA researchers in the Netherlands and universities in Norway, Spain and Italy under the Ariadna initiative “allowed us to look into such an exploratory, somewhat risky idea that can bring valuable results not only for space exploration, but also for technology applications on Earth,” explains out Marlies.

“Industry could benefit from refined recipes for fire and heat resistant inorganic polymers suitable for additive manufacturing,” she adds.

One of the hot topics the team wants to tackle next is how basalt fibres from the Moon could reinforce the concrete and how the material could be best used to shield a lunar colony. Researchers hope that this new urea-based mortar could help protect future astronauts from harmful levels of ionising radiation.