Dr. Nick Smith is the ESA-sponsored medical doctor spending 12 months at Concordia research station in Antarctica for the 2020-21 season. He facilitates a number of experiments on the effects of isolation, light deprivation, and extreme temperatures on the human body and mind.

Monday 19 th October

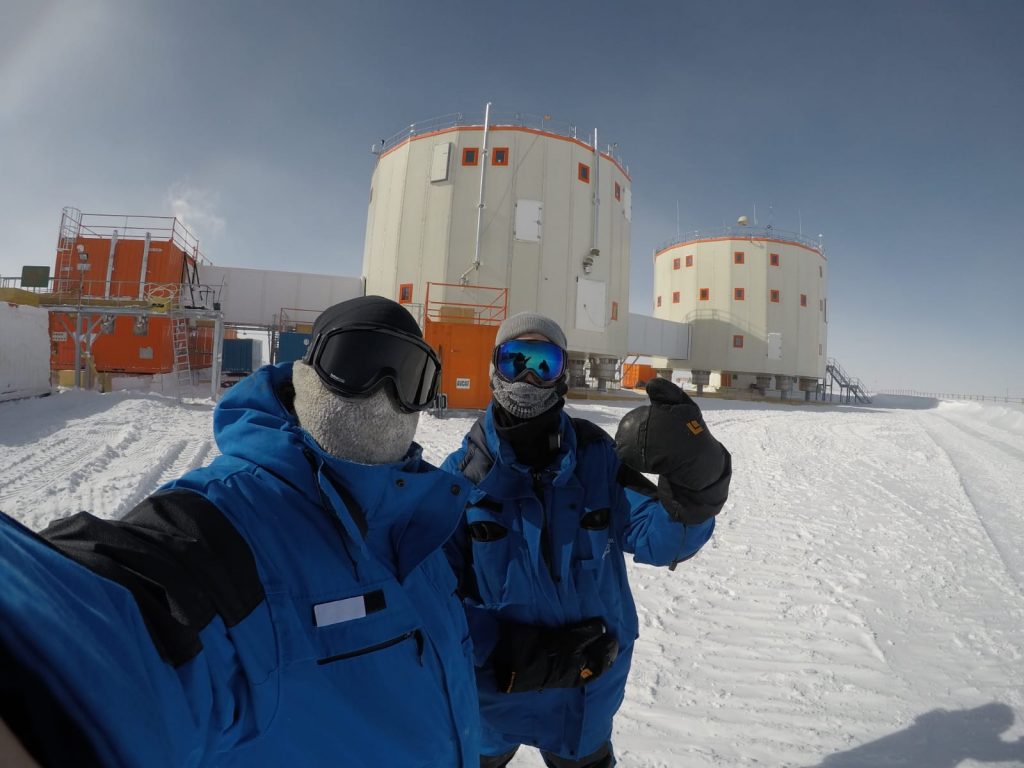

Hello everyone, and welcome to my blog! My name is Nick Smith and I am the European Space Agency’s research Medical Doctor (MD) for the winter-over period 2020-21 at Concordia Station, Antarctica. This is my first entry of many in which I aim to describe the journey from what motivated me to apply, all the way through to coming home. Roughly speaking, we’re looking at a two-year journey here, about 12-14 months of it spent on the Antarctic continent itself.

Before we dig in, I feel I should add a little about myself and my background, for context. After leaving school I started my training to become a vehicle mechanic; my ambitions and interests eventually led me to join the British Army, being offered a position to train as an aircraft technician.. Six years later, after a number of exercises, an operational tour and promotion to Corporal, I decided it was time to move on; for me, this meant becoming a doctor. A year in London learning basic medical sciences was followed by a 5-year medical degree at the University of Southampton, and a two-year foundation programme in Northern Scotland. It was during these last two years that I found and applied for the ESA research MD role.

Rewind to a pre-COVID era, Christmas 2019.

I spotted the role advertised on a rare quiet night shift on the labour ward. The application forms asked questions about my health and my reasons for applying. They cautioned the risks involved to the physical and psychological and asked for calm and sensible people to apply. The forms themselves were rather daunting, but I filled them out anyway and stuffed them in my bag.

I waited until daytime to reassess what I had written (night shifts make you a little wild) then sent it right before the deadline. Up until that point, I was considering (as most doctors at this level do!) taking a year out of formal training to get a little more general experience, perhaps even move closer to my family. Instead, I was sitting in front of my laptop, applying for a job that was so far removed from my initial plans. I felt the weight of my decision.

But my mind was made up, and as soon as I sent the application, I became immediately excited at the prospect of being part of such a peculiar, fantastic opportunity. To my astonishment, I received an email the next day inviting me for an interview and medical assessment in a mere two weeks’ time.

Before I knew it, I had acquired the medical and dental certificates asked of me and was on my way to the French Polar Institute and TAAF offices in Paris, where the interview would be conducted. The interview itself consisted of a morning of very thorough medical assessments, followed by an in-depth psychological examination and the actual interview itself. It was an intense day, but the effort paid off when a little over three weeks later, while out shopping with my Mum, I received an email offering me the job. While I pondered the practicalities of what may come, I felt my life creak and lurch to find a new heading through rarely sailed waters, as I typed a rather excitable acceptance email to ESA telling them I’m their guy.

So why would anyone want to throw themselves so far away? Bear with me.

As my life canters on I occasionally have brief instances in which a sense of clarity and objectivity washes over me. They seem to happen at particularly poignant moments. from standing on top of an Apache helicopter in the deserts of Arizona, to the deafening silence of Svalbard’s fjords. They are somewhat removed and distant; a moment in which I can look from above at my present as a function of the decisions I have made thus far. It was in one of these moments during the back end of medical school that I noticed a pattern in my life of gravitating towards the remote and isolated. One finds in these far-flung places not only rampant untouched beauty, but also those resilient people that provide so much to society, yet live so far away from its embrace. Such separation, often done happily and voluntarily, entails forgoing not only the trivial comforts available in cities and larger towns, but also the standard of living that accompanies it – especially regarding healthcare.

The most beautiful places are often those far removed from humanity’s immediate reach. At first sight, Buzz Aldrin described the Moon as “magnificent desolation” – I believe that I will find something akin to this at Concordia Station.

Over time, I have become increasingly fascinated with remote places and the people living and working there, and more concerned with their wellbeing and the effects their isolation has upon them – not to mention a question I regularly ask myself – “Could I do that?”. I have always been a man of extremes – all or nothing – and what is the most extreme form of remoteness we have? Space. Enter ESA and the research MD role. Over a year living at Concordia station, a place analogous to living on another planet. Being sponsored to perform research into the effects of isolation and remoteness on those scientists and technicians that live and work there was a perfect nexus of all my personal and professional interests. While intimidating, it was a natural next step for me, and a challenge I am excited to undertake and overcome.

Next time I’ll describe the training required ahead of my deployment and a little about how COVID-19 affected that (spoiler alert – it affects everything). Ciao!

Discussion: 9 comments

succes nick!

I’m happy to see you

Best wishes for xmas and new year’s

Love from French family

Hi Nick,

you are following a fantastic career. Few people achieve what you have done and are doing. A very happy new year to you.

Brilliant! Love all the background info, looking forward to hear the next entry

What a life experience you must be having! Keep us updated ?

Good luck Dr Nick ?

I just started med school, I’m in my 30s, and working in Antarctica has always been one of my goals. At least since I was 20-ish. I used to work in a whole different industry too (which allowed me to sail up in the Arctic), before before med school.

I hope I get the same opportunity when I’m done. It’s nice to know about your background, it gives me some hope !

Thanks for sharing and being a role model ! 🙂

Good luck Nick, just thought of you…did a google search and look what I found! Hope to speak soon.

Good luck Nick…just thinking of you, Googled your name and look what I found! Hope to speak soon. All the best.