Dr. Stijn Thoolen is the ESA-sponsored medical doctor spending 12 months at Concordia research station in Antarctica. He facilitates a number of experiments on the effects of isolation, light deprivation, and extreme temperatures on the human body and mind. Find this blog post in the original Dutch below.

Concordia, July 28, 2020

Sunlight: none, but the skies are turning colors again!

Windchill temperature: -83°C

Mood: some days a little tired, and on others, like the skies, full of color

If you have read my previous posts, you have probably had enough of the beautiful-environment-and-working-together-drivel, and I am guessing you are now thinking something along the lines of: weren’t you supposed to do space research?

Good question, and it makes me realize that perhaps it is time for something more interesting: science!

But I am not sure if an ESA blog can go without any music, so before we continue here is a nice tune to walk you through:

I already mentioned what a science-heaven Concordia actually is. From paleoclimatology to geophysics to astronomy: science is the whole reason that this station exists. But while most of it focuses on the unique environment we currently live in, ESA is rather interested in us living in this unique environment! Both the Antarctic and space are domains that we, humans, have started to explore only recently, and the mismatch between our ancient bodies and these new extreme environments poses the ultimate challenge to our system. How adaptable are we? Where lies the limit of our human resilience? What are the risks to our physical and mental health when we venture to these strange places, how does that impact future space travel, and are there ways to mitigate those risks? So, rather than the environment itself, it is our interaction with it that I find particularly interesting.

Take, for example, the altitude. Here in Concordia we live at an altitude that is equivalent to about 3800 meters above sea level at the equator. As such, the air contains about 40% less oxygen for us to breath, and you definitely feel that when you arrive here by plane. Low energy, panting with the slightest exercise, waking up gasping for air multiple times a night, headache, dizziness, loss of appetite. Some really get sick from it, and in rare cases people have to be sent back to the coast due to life-threatening build-up of fluid in the lungs or brain! Yet, in 1978 Messner and Habeler reached the summit of Mount Everest at an altitude of 8848 meters without using any supplemental oxygen at all. How? They allowed time for their bodies to adapt.

At Concordia it usually takes a few days before you feel better. As your body senses a decrease in oxygen pressure it immediately tries to save your cells from getting damaged by sucking in more air (breathing) and pump more oxygen through the body (by increasing heart rate), and subsequently starts up a remarkable cascade of physiological processes that eventually leads to an increased production of red blood cells. As a result, the composition of our blood can drastically change over weeks, to help deliver sufficient oxygen to each of our cells. Pretty cool, don’t you think? Even though after eight months I still find myself hyperventilating up the stairs and having miserable nights every once in a while, at least it allows me to go to beautiful places like Concordia!

The adaptation however comes with a trade-off: if the need for oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood is too high (at higher altitudes, where there is less oxygen) and too many red blood cells are made, the blood can become so thick that it increases the risk of blood clotting, high blood pressure in the lungs, and even heart failure! Such health issues have been seen in some people living permanently at high altitude. So how healthy actually is a year of adaptation at Concordia? Knowing that similar low oxygen conditions may exist in future space habitats for technical, economical and safety reasons, and considering the simultaneous blood volume alterations usually seen as an effect of microgravity, answering that question is important to understand astronaut health and safety during future long-duration space missions.

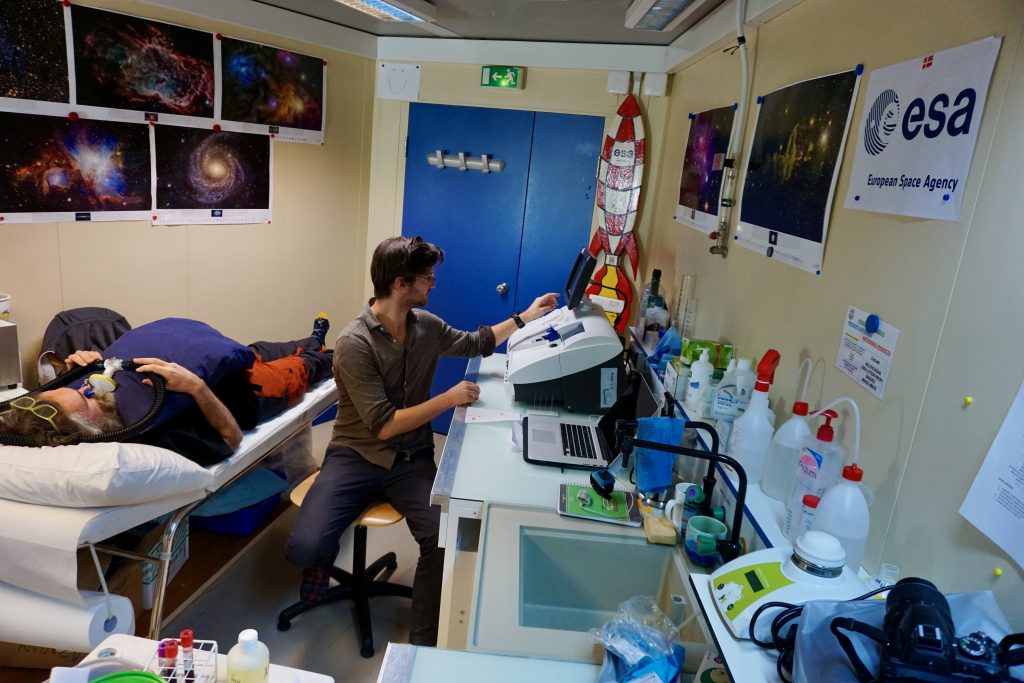

The ANTARCV study (‘alterations in total red blood cell volume and plasma volume during a one-year confinement in Antarctica: effect of hypoxia’) is implemented this year to do so. Each month the crew comes to the ESA lab for a lucky treatment of vein punctures, and an awkward procedure of breathing a very small and safe dose of carbon monoxide through small, restrictive tubes. This way I can determine our blood volumes. Besides I analyze how thick our blood is, store blood samples for further analysis in Europe, and we all wear a watch one week a month to record our activity. That way we make sure that the changes we see in blood volumes are not just a result of changes in physical activity. You can understand the crew loves me for it…

Still, all of us are participating in the research, and that is awesome! You see, doing human research here can be quite a challenge, not only because of language barriers, limited data transfer possibilities, or complex transportation logistics, but mostly so because the participation in these experiments is entirely voluntary. None of us works here primarily to serve as a test subject, and it is not that I can force anyone really… So to make sure I come home after a year with sufficient interesting data, I better make sure that everyone is happy with what we are doing here. For me perhaps a tricky mix between work and private life, but all for the good cause of science! After all, who doesn’t want to be part of the space program, bring benefit to future hivernauts and astronauts, and on top of that help to understand health challenges of our present-day society?

Concordia, 28 juli 2020

Zonlicht: geen, maar de hemel krijgt weer kleur!

Gevoelstemperatuur: -83°C

Gemoedstoestand: soms wat moe, en soms, net als de hemel, kleurrijk

Als je mijn vorige blogs hebt gelezen zal je nu wel genoeg gehad hebben van al dat bijzondere-omgeving-en-samenwerken-gezever, en ik kan me voorstellen dat je zoiets denkt als: maar moest jij daar geen ruimtevaartonderzoek doen?

Goeie vraag, en ik realiseer me dat het tijd is voor iets veel interessanters: wetenschap!

Maar ik weet niet zeker of een ESA-blog wel zonder muziek kan, dus voordat we verder gaan is hier een lekker deuntje om je er doorheen te loodsen:

Ik heb eerder al wel eens gezegd wat voor een wetenschaps-walhalla Concordia is. Van paleoklimatologie tot geofysica tot astronomie: wetenschap is de hele reden dat dit station bestaat. Maar terwijl het meeste ervan zich richt op de unieke omgeving waarin we leven, is ESA meer geïnteresseerd in hoe wij leven in deze unieke omgeving! Zowel Antarctica als de ruimte zijn terreinen die wij, mensen, pas sinds kort zijn gaan ontdekken, en de mismatch tussen onze oeroude lichamen en deze nieuwe extreme omgevingen stelt ons systeem voor de ultieme uitdaging. Hoe groot is ons aanpassingsvermogen? Waar ligt de grens van onze menselijke veerkracht? Wat zijn de risico’s voor onze fysieke en mentale gezondheid als we ons op dit soort vreemde plaatsen wagen, wat voor impact heeft dat op toekomstige ruimtereizen, en zijn er manieren om die risico’s tegen te gaan? Meer dan de omgeving zelf, vind ik vooral onze interactie ermee interessant.

Neem bijvoorbeeld de hoogte. Hier in Concordia leven we op een hoogte die equivalent is aan zo’n 3800 meter boven zeeniveau op de evenaar. De lucht bevat daardoor zo’n 40% minder zuurstof voor ons om in te ademen, en dat voel je wel wanneer je hier met het vliegtuig aankomt. Geen energie, buiten adem bij de geringste inspanning, meerdere keren per nacht snakkend naar adem wakker worden, hoofdpijn, duizeligheid, verminderde eetlust. Sommigen worden er echt ziek van, en in zeldzame gevallen moeten mensen zelfs teruggestuurd worden naar de kust vanwege een levensbedreigende toename van vocht in de longen of hersenen! Toch konden Messner en Habeler in 1978 de top van Mount Everest bereiken op een hoogte van 8848 meter zonder enige extra zuurstof. Hoe? Zij gaven hun lichaam de tijd om zich aan te passen.

Het duurt in Concordia meestal enkele dagen voordat je je beter voelt. Op het moment dat je lichaam een afname in de zuurstofdruk opmerkt, probeert het onmiddellijk te voorkomen dat je cellen beschadigd raken door meer lucht op te zuigen (ademen) en meer zuurstof door het lichaam te pompen (door de hartslag te verhogen), om vervolgens een wonderlijke cascade van fysiologische processen op te starten die er uiteindelijk voor zorgt dat er meer rode bloedcellen worden aangemaakt. De samenstelling van ons bloed kan daardoor binnen enkele weken drastisch veranderen, om ervoor te zorgen dat er naar iedere cel voldoende zuurstof geleverd wordt. Best wel gaaf, toch? En al kom ik na acht maanden nog steeds hyperventilerend de trap op en kunnen de nachten af en toe nog altijd vrij belabberd zijn, ik kan hierdoor tenminste wel naar prachtige plekken zoals Concordia!

Maar de aanpassing komt met een compromis: als de behoefte aan zuurstofdragend vermogen van het bloed te hoog is (op grotere hoogtes, waar minder zuurstof is) en te veel rode bloedcellen worden aangemaakt, kan het bloed zo dik worden dat het risico op bloedstolling, hoge bloeddruk in de longen, en zelfs hartfalen hoger wordt! Zulke gezondheidsproblemen komen voor bij sommige mensen die permanent op grote hoogte leven. Dus hoe gezond is het nou eigenlijk om je een jaar aan te passen in Concordia? Vanwege technische-, economische- en veiligheidsredenen kunnen vergelijkbare condities voorkomen als we op een andere planeet leven, en gezien de veranderingen in bloedvolumes die bovendien kunnen optreden in de ruimte als gevolg van gewichtloosheid, is het beantwoorden van die vraag belangrijk voor de gezondheid en veiligheid van astronauten tijdens langdurige ruimtemissies in de toekomst.

De studie ANTARCV (‘alterations in total red blood cell volume and plasma volume during a one-year confinement in Antarctica: effect of hypoxia’) wordt daarom dit jaar hier uitgevoerd, om dit te leren begrijpen. Elke maand komt de bemanning naar het ESA-lab om bloed te laten prikken, en door een stel kleine, benauwende slangen een kleine en veilige dosis koolstofmonoxide in te ademen. Zo kan ik onze bloedvolumes bepalen. Daarnaast analyseer ik hoe dik ons bloed is, bewaar ik bloedmonsters voor verdere analyse in Europa, en dragen we allemaal een horloge voor een week per maand om onze activiteit te meten. Op die manier weten we zeker dat de veranderingen in bloedvolumes niet alleen het gevolg zijn van lichamelijke activiteit. Je begrijpt met dit alles dus wel hoe blij de bemanning met me is…

Toch nemen we allemaal deel aan het onderzoek, en dat is geweldig! Onderzoek doen op mensen kan hier namelijk best een uitdaging zijn, niet alleen vanwege de taalbarrières, beperkte mogelijkheden voor dataoverdracht, of complexe transportlogistiek, maar met name omdat deelname aan deze experimenten volledig vrijwillig is. Niemand van ons werkt hier in eerste instantie om proefpersoon te zijn, en ik kan nou ook niet echt iemand dwingen… Om er dus voor te zorgen dat ik thuiskom met voldoende interessante data, kan ik er maar beter voor zorgen dat iedereen gelukkig is met wat we hier doen. Voor mij misschien een listige mix tussen werk en privéleven, maar allemaal voor de goede zaak van de wetenschap! Want wie wil er nou niet deel uitmaken van het ruimtevaartprogramma, toekomstige hivernauten en astronauten helpen, en bovendien bijdragen om de hedendaagse uitdagingen in de gezondheidszorg beter te leren begrijpen?

Discussion: 4 comments

Wonderful work …

so interesting to read!!

Dear Sirs,

We would kindly appreciate these sincere efforts in respect to facilitates a number of experiments on the effects of isolation, light deprivation, and extreme temperatures on the human body and mind.

We would kindly to point out the necessity of separating rest of factor which have also the same effects upon human body than the recent factor, (windchill temperature -83°C, the altitude is equivalent to about 3800 meters above sea, the air contains about 40% less oxygen for us to breath, etc) which are the goal of the investigations in Concordia.

Therefore we kindly request you to investigate this issue of the health of human in these mentioned circumstances when the crew members have their vegetable resources foods only and stop consuming a meat products (for a several months).

Because meat products granting the possibility of passing the heavy oils to human body, which represents a one of obstacles to breathe normally, and also results the headache, when these oils stabilize in the human lung, despite of the effects of the DNA of the animals in human vital system, in order to investigate this issue precisely and get the required data in the required circumstances, because having foods of the vegetable resources for a several months will prevent interning the heavy oils of animals to the lung nor the DNA of animals to the human body, thus we could get a clear picture and vision of this issue, to clarify exactly the effects of these mentioned circumstances in the antarctica upon the human body and vital activities during the absence of rest of factors which have the same effects upon the vital activities of the human body, therwise these data will not be quite precise in these circumstances, otherwise these data of experiments will not be quite precise for these circumstances.

Good luck.

Thank you for all the great posts, the insight, interest and nostalgia they inflict!

Looking forward to welcoming you back and listening to all your stories!

Best wishes to the whole team for these last weeks and the home-bound journey.

Adri