Dr. Stijn Thoolen is the ESA-sponsored medical doctor spending 12 months at Concordia research station in Antarctica. He facilitates a number of experiments on the effects of isolation, light deprivation, and extreme temperatures on the human body and mind. Find this blog post in the original Dutch below.

Concordia, April 7, 2020

Sunlight: about 10 hours

Windchill temperature: -72°C

Mood: just fine

It is quite strange to be here, on the only continent not affected by the corona virus. To me, with everything that is currently going on in the rest of the world, it makes feel even more distant than we already are. Here life just goes on, and although it has not been easy for some of us either, not being able to share in these experiences or provide support at home to those who could use it, messages are now suggesting that we are suddenly the ones better off!

And I have to admit indeed. Even though we are stuck here for nine months without any possibility for evacuation, with limited resources, a disrupted work/leisure balance, a threatening environment outside, both environmental and social monotony, and a group of relative strangers that come from all sorts of backgrounds (reading this I guess the situation for you may perhaps not be so different), at least we came here by choice…

So let me start with saying that I really hope you are doing well. Being isolated and confined comes with all kinds of stressors, deviations from the normal situation you could say, that ask our body and mind to adapt. Given the sudden disruption that the Corona outbreak has caused to all of you, I imagine that is certainly not easy.

And while our experiences are so different, and even though I feel probably as ignorant as you about how to deal with all those stressors (we have just been left to ourselves two months ago), perhaps this is a good time to share with you some of my own thoughts about isolation at Concordia.

A while ago I came across a story about the 1897-1899 Belgian Antarctic Expedition, which I found quite illustrative for what I have considered to make my winterover a happy one this year. At the time the Antarctic was still mostly unknown territory. The south pole was not yet reached, and the unforgiving environment made many expeditions end in disappointment. Aimed for exploration and for science, this one was no exception. When their ship the Belgica got stuck in the pack ice of the Bellingshausen Sea, the 19-member crew became the first in human history to winterover below the Antarctic circle, and as such you can imagine they were badly prepared to do so. It must have been pretty difficult, I imagine. Expedition doctor Frederick Cook described depression, irritability, headaches and sleeplessness among the crew, and basically provided a first recorded description of the so-called ‘winterover syndrome’.

“The curtain of blackness which has fallen over the outer world of icy desolation has also descended upon the inner world of our souls” – Frederick A. Cook, 1900

The strange and extreme Antarctic environment, just like in space, indeed has a strong capability to upset our system. Symptoms like fatigue, headaches, sleep disturbances, impaired cognition, negative emotions such as depression, anxiety and anger, and interpersonal conflicts have all been observed in polar dwellers. Such symptoms are usually more prevalent during the harsh winter months, when stressors are highest. Hence the ‘winterover syndrome’. For the winterover crew of 1898, Dr. Cook reasoned that what they needed that was the opposite of that harsh winter environment. Apparently with good effect, he prescribed them a diet of milk, fresh meat (poor penguins) and cranberry juice, as well as exercise, warmth and light. Interesting I think, not necessarily his particular ‘baking treatment’ of having the crew sit naked around an open fire, but the way it shows how dependent we are on our environment, and our limitations to adapt. In other words, to facilitate adaptation, we may want to create an environment that is more familiar to us.

For here in Concordia, or perhaps for something as different and unexpected as a Covid-19 lockdown, I like to think the idea is quite similar. I therefore try to maintain a daily rhythm full of activities that mimic a little bit the world we come from. I try to wake up and go to bed at regular times to promote sleep and maintain a functioning biological clock (without sunlight it relies even more on social clues), and while I restrict myself as much as possible from bright computer screens in the evening hours, an artificial daylight is standing by in my office for the darkest months. Elisa, our cook, is making us pretty balanced meals twice a day, and even though I have to admit I eat a lot here (altitude plus cold equals many burned calories), I take vitamin D in addition to make up for the lack of sunlight. About three times a week I visit the gym (it got a little too cold outside) to stimulate myself physically, and if not working, sleeping, eating, or exercising, I try to stimulate my senses by an impact from the magnificent world outside, playing games together, or reading a book. Socially, I try to stay connected with my friends and family at home, and with the crew we regularly have video connections with schools for outreach purposes, and even with each other’s families. We are social beings after all, and we may easily become lonely if we don’t feel part of the group (whichever group that may be…). Finally, to relieve some of the excess amount of stress here, I try to practice meditation each morning, and for the same reasons we have our sauna (yes, sauna) open on Sunday’s. Perhaps it really is a paradise…

But while I like to believe that maintaining such a routine may already give us a handful of things to distract us from boredom and unfilled time (which is perhaps more stressful than no time), I wonder if it will be enough to get us through those nine monotonous months. At home, the world around us is constantly changing, providing us with new input every day. New people, new weather, new smells, new tastes, new projects, new whatever. Rather than just routine, such novelty may be as important to prevent us from being under-stimulated. It may require a bit of creativity though…

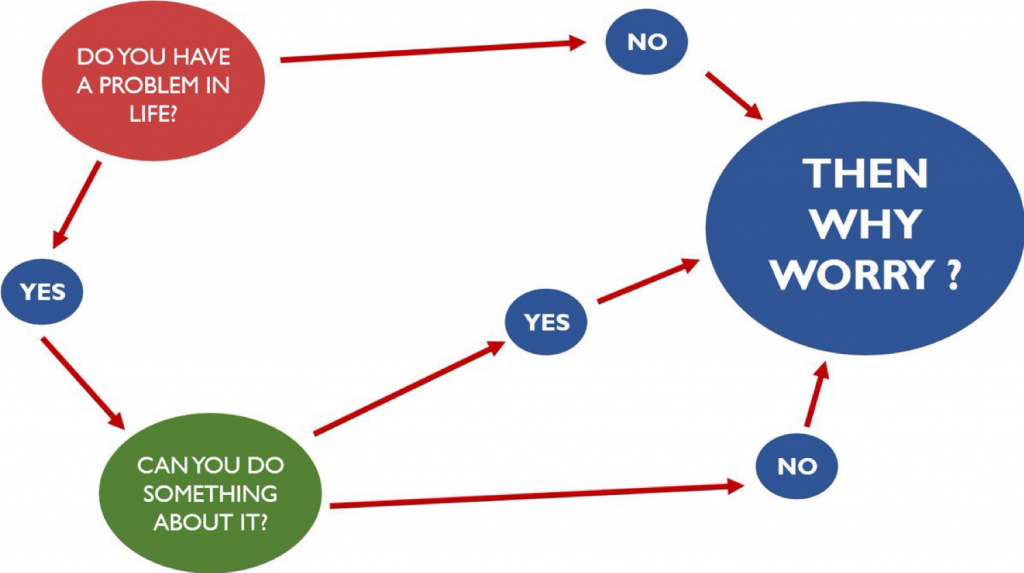

Doing all these things that you may not be used to do at home is not always easy, and from a psychological point of view (and that is where I believe you can really make a difference), it requires effort. Sometimes you may want to act in a way that seems beneficial to you, but actually has an opposite effect on the long term (I think we all recognize that idea, not?). For me, this is perhaps the biggest challenge this year: to be able to maintain my motivation to bring up that discipline, to see that ‘bigger picture’, and be able to understand what brought me here in the first place, especially when exposed to those winter stressors. Those are the moments we tend to become more self-oriented, and lose our perspective to the world outside.

Perhaps that is also the main reason for interpersonal conflict to occur so often during polar expeditions. Differences in gender, occupation, interests, opinions: all of them may become an irritant if we forget that we are not all like ourselves. Knowing that such relational problems are among the greatest stressors for winteroverers (so indeed we are social beings after all), we better bring up the discipline to maintain that flexibility and tolerance for each other. Here more than anywhere else we need to actively maintain our relationships by respecting communal tasks and privacy, and mood variations and different opinions. And perhaps those awkward communication and team bonding exercises during pre-departure training weren’t so stupid after all, rather helping us in that effort to understand each other’s actions and intentions. Acting against our instincts may be difficult sometimes, but in that self-control, or self-improvement rather, I see my individual moral responsibility this year.

It is certainly not going to be an easy year, and we still have many months to go. It will ask a lot of flexibility to deal with its strangeness, deprivations, and stresses. But as I have mentioned in a previous blog post, I like to think that it has its positive sides as well. Often seen in Antarctic winterover expeditions, sharing and overcoming such challenges may fill us with a sense of accomplishment, increased self-esteem, larger problem-solving capabilities, and social proximity to others (how contradicting that now may sound…). Being taken out of the comfort of our daily routine may give us an opportunity to see the precious things that we usually like to take for granted. It can show us how much we depend on each other, and how vulnerable we can be. To me, that is a very valuable experience.

So maybe we can imagine we are all polar dwellers these days, or astronauts if you prefer. While I wish that the damages done by the Corona virus will soon come to an halt, and that everyone is able to overcome their personal challenges, I can only hope that the current lockdown experience will one day bring you something that we can share after all. That sense of humility, we could then call perhaps the ‘Corona-over syndrome’.

And, in case being locked inside is making you feel as corny as our conversations here at the dinner table, this may be the right song to end this blog in style:

On behalf of the DC16 crew here at Concordia, even though we are thousands of kilometers away, we are close to you in thought!

Groeten uit het paradijs!

Concordia, 7 april 2020

Zonlicht: zo’n 10 uur

Gevoelstemperatuur: -72°C

Gemoedstoestand: prima

Het is best wel vreemd om hier te zijn, op het enige continent niet aangedaan door het Corona virus. Met alles wat er op het moment gaande is in de rest van de wereld, voel ik me nu nog meer afgezonderd dan dat we al zijn. Hier gaat het leven gewoon door. Ondanks dat het voor sommigen van ons hier ook niet makkelijk is geweest, om niet te kunnen delen in deze ervaringen of om hulp te kunnen bieden thuis aan diegenen die het zouden kunnen gebruiken, blijkt uit de berichten dat wij hier ineens beter af zijn!

En ik moet inderdaad toegeven. Zelfs al zitten we hier vast voor negen maanden zonder enige mogelijkheid tot evacuatie, met beperkte middelen, een verstoorde werk/vrijetijdsbalans, een bedreigende omgeving buiten, zowel fysieke als sociale eentonigheid, en een groep mensen met de meest uiteenlopende achtergronden die relatief vreemd is van elkaar (nu ik dit lees vraag ik me af of de situatie zo anders is voor jullie), voor ons was het tenminste een keuze…

Laat ik dus maar beginnen te zeggen dat ik werkelijk hoop dat het goed gaat met jullie. Isolatie en opsluiting komt met allerlei stressoren, afwijkingen van de normale situatie zou je kunnen zeggen, die van ons lichaam en geest nogal wat aanpassingsvermogen vragen. Gezien de zo plotselinge verstoring die de Corona uitbraak heeft veroorzaakt, kan ik me voorstellen dat dat niet bepaald gemakkelijk is.

En terwijl onze ervaringen zo anders zijn, en ondanks dat ik me waarschijnlijk even onwetend voel als jullie over hoe met al die stressoren om te gaan (wij zijn ook pas sinds twee maanden op onszelf aangewezen), is dit misschien een goede tijd om wat van mijn eigen gedachten over isolatie in Concordia met jullie te delen.

Een tijd geleden stuitte ik op een verhaal over de 1897-1899 Belgische Antarctische expeditie, en ik vond dit best illustratief voor wat ik zelf heb overwogen om mijn overwintering tot een goed einde te brengen dit jaar. Antarctica was in die tijd nog voornamelijk onbekend gebied. De zuidpool was nog niet bereikt, en de meedogenloze omgeving zorgde ervoor dat veel expedities uitliepen op teleurstelling. Gericht op verkenning en wetenschap, was deze expeditie geen uitzondering. Toen hun schip de Belgica vast kwam te zitten in het pakijs van de Bellingshausenzee, werd de 19-koppige bemanning geforceerd om als eerste in de geschiedenis de winter door te brengen binnen de zuidpoolcirkel, en je kunt je wel voorstellen dat ze daar slecht op voorbereid waren. Het moet een hele uitdaging geweest zijn, stel ik me zo voor. Expeditiearts Frederick Cook beschreef symptomen van depressie, prikkelbaarheid, hoofdpijn en slapeloosheid onder de bemanningsleden, en was eigenlijk de eerste die in een beschrijving voorzag van het zogenaamde ‘winterover syndrome’.

“The curtain of blackness which has fallen over the outer world of icy desolation has also descended upon the inner world of our souls” – Frederick A. Cook, 1900

De vreemde en extreme omgeving van Antarctica, net als in de ruimtevaart, heeft inderdaad een sterk vermogen om ons systeem te ontregelen. Symptomen als vermoeidheid, hoofdpijn, slaapproblemen, verminderde cognitie, negatieve emoties zoals depressie, angst en woede, en interpersoonlijk conflict zijn allemaal beschreven bij poolreizigers. Zulke symptomen zijn meestal meer uitgesproken gedurende de strenge wintermaanden, als de stressoren het sterkst zijn. Vandaar het ‘winterover syndrome’. Voor de overwinteraars van 1898 beredeneerde Dr. Cook dat zij het tegenovergestelde van die strenge winteromgeving nodig hadden. Blijkbaar met goed resultaat schreef hij hen een dieet voor van melk, vers vlees (arme pinguïns) en cranberrysap, evenals lichaamsbeweging, warmte en licht. Interessant vond ik, niet zozeer zijn opmerkelijke ‘baking treatment’ waarbij hij de bemanning naakt rondom een open vuur liet zitten, maar meer vanwege de manier waarop het laat zien hoe afhankelijk we zijn van onze omgeving, en beperkt in ons aanpassingsvermogen. In andere woorden, om zulke aanpassing te ondersteunen zouden we misschien een omgeving moeten creëren die ons wat meer vertrouwd is.

Voor hier in Concordia, of misschien voor zoiets afwijkends en onverwachts als een Covid-19 lockdown, kan ik me voorstellen dat het idee vergelijkbaar is. Ik probeer daarom een dagelijks ritme aan te houden vol activiteiten die de wereld waar we vandaan komen een beetje nabootst. Ik probeer op vaste tijden op te staan en naar bed te gaan voor een betere slaap en om mijn biologische klok niet te veel te laten ontregelen (zonder zonlight is die nog meer afhankelijk van sociale input), en terwijl ik mezelf in de avonduren zoveel mogelijk van heldere computerschermen onthoud, staat een daglichtlamp klaar in het ESA-lab voor de meest donkere maanden. Elisa, onze kok, maakt voor ons twee keer per dag vrij gebalanceerde maaltijden klaar, en ondanks dat ik moet toegegeven dat mijn porties hier nogal zijn toegenomen (hoogte plus kou is veel verbande calorieën), neem ik extra vitamine D om te compenseren voor het tekort aan zonlicht. Zo’n drie keer per week ga ik naar de sportschool (het is wat te koud geworden buiten) om mezelf fysiek te stimuleren, en als ik niet aan het werken, slapen, eten of bewegen ben, probeer ik mijn zintuigen en verstand wakker te schudden door een visite aan de schitterende wereld buiten, of door samen spelletjes te spelen, of een boek te lezen. Sociaal gezien probeer ik in contact te blijven met mijn vrienden en familie thuis, en met de crew hebben we regelmatig videogesprekken met scholen, en zelfs met elkaars families. We zijn nu eenmaal sociale wezens, en we kunnen gemakkelijk vereenzamen als we ons niet onderdeel voelen van de groep (welke groep dat dan ook mag zijn…) Ten slotte, om de overmatige stress hier wat te verlichten, probeer ik iedere ochtend te mediteren, en om vergelijkbare redenen hebben we hier zelfs een sauna (ja, sauna) open op zondagen. Misschien is het hier dan toch een paradijs…

En hoewel ik graag geloof dat het onderhouden van zo’n routine ons al een handvol aan bezigheden aanreikt die ons kan leiden van de saaiheid en ongevulde tijd hier (wat misschien wel meer stress oplevert dan geen tijd), vraag ik me af of het genoeg zal zijn om ons door die negen eentonige maanden heen te loodsen. Thuis verandert de wereld om ons heen voortdurend, en worden we elke dag van nieuwe input voorzien. Nieuwe mensen, weersveranderingen, nieuwe geuren, nieuwe smaken, nieuwe projecten, nieuwe wat dan ook. Naast alleen routine is zulke nieuwigheid of verrassing misschien wel even belangrijk om te voorkomen dat we onderprikkeld raken. Het vereist alleen wat creativiteit misschien…

Maar al dit soort dingen doen waarvan je dat thuis niet gewend bent is niet altijd gemakkelijk. Vanuit een psychologisch oogpunt (en dat is denk ik waar je echt het verschil kan maken) vereist dat inspanning. Soms wil je misschien op een manier handelen die voordelig voor je lijkt, maar eigenlijk een tegenovergesteld effect heeft op de lange termijn (ik geloof dat we dat allemaal wel herkennen, niet?). Dat is voor mij persoonlijk misschien wel de grootste uitdaging dit jaar: om de motivatie te behouden om die discipline op te kunnen brengen, om dat ‘grotere plaatje’ te zien, en te blijven beseffen wat me hier in de eerste plaats gebracht heeft, met name tijdens die stressvolle wintermaanden. Het zijn met name die momenten dat we geneigd om ons op onszelf te richten, en we ons perspectief op de buitenwereld verliezen.

Dat is misschien ook wel de voornaamste reden dat interpersoonlijk conflict zo vaak voorkomt tijdens poolexpedities. Verschillen in geslacht, beroep, interesses, meningen: allemaal kunnen ze irritaties opleveren als we vergeten dat we niet allemaal hetzelfde zijn. We weten dat zulke relationele problemen onder de grootste stressoren vallen voor overwinteraars (inderdaad dus, we zijn nu eenmaal sociale wezens), dus beter brengen we die discipline op om ons flexibel en tolerant naar elkaar te kunnen blijven opstellen. Hier meer dan waar ook op aarde moeten we onze relaties actief onderhouden, door zowel gemeenschappelijke taken als privacy te respecteren, en stemmingswisselingen en meningsverschillen. Misschien waren die ongemakkelijke communicatieoefeningen en teambuilding activiteiten tijdens onze training zo gek nog niet, en hebben ze ons een beetje geholpen in onze poging elkaars acties en bedoelingen beter te begrijpen. Handelen in strijd met ons instinct is misschien niet altijd makkelijk, maar in die zelfbeheersing, zelfverbetering liever, zie ik mijn individuele morele verantwoordelijkheid dit jaar.

Een makkelijk jaar wordt het zeker niet, en we hebben nog genoeg maanden te gaan. Het zal een hoop flexibiliteit van ons vragen om te kunnen omgaan met deze vreemdheid, deprivaties en stressoren. Maar zoals ik in een eerdere blog heb genoemd, geloof ik dat dit alles ook zijn positieve kanten heeft. Zoals vaker gezien in expeditieleden die in Antarctica overwinteren, kan het delen en overwinnen van zulke uitdagingen ons een gevoel van vervulling en zelfvertrouwen geven, een toegenomen probleemoplossend vermogen, en zelfs sociale betrokkenheid tot anderen (hoe tegenstrijdig dat nu ook mag klinken…). We bevinden ons even uit het gemak van onze dagelijkse routine, en dat geeft ons de mogelijkheid om waardevolle dingen te zien die we normaal gesproken zo voor lief nemen. Het kan ons laten zien hoeveel we op elkaar aangewezen zijn, en hoe kwetsbaar we eigenlijk kunnen zijn. Een hele waardevolle ervaring, lijkt mij.

Dus misschien kunnen we ons voorstellen dat we deze dagen allemaal een beetje poolbewoner zijn, of astronaut als je liever hebt. Terwijl ik wens dat de schade die het Corona virus brengt snel tot een einde komt, en dat iedereen zijn persoonlijke uitdagingen te boven weet te komen, dan kan ik alleen maar hopen dat de huidige isolatie ervaring uiteindelijk ook iets met zich mee brengt dat we dan toch met elkaar kunnen delen. Dat gevoel van nederigheid, misschien moeten we dat dan het ‘Corona-over syndrome’ noemen…

In het geval dat je je na al die dagen binnen zitten net zo melig voelt als onze gesprekken aan de eettafel hier, dan is dit misschien het goede nummer om deze blog in stijl te eindigen:

Namens de DC16 crew hier in Concordia: we zijn misschien duizenden kilometers van jullie verwijderd, maar in gedachte blijven we dichtbij!

Discussion: one comment

Are you interested in space Astronomy information, then this blog is for you.

Topic : Impression of Planet Proxima Centauri with New the stars, Centauri a and Centauri B

Proxima Centauri