Taken from ESA-sponsored medical doctor Floris van den Berg’s blog:

Most people assume the famous line “that’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind” by Neil Armstrong were the first words spoken on the moon, but actually Buzz Aldrin beat him to the punch by confirming contact with the lunar surface upon landing.

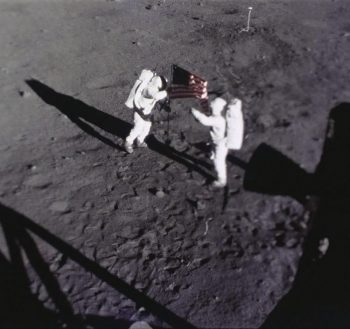

As the second person to ever walk on the moon, Aldrin clearly described his view as being “magnificent desolation”. Stepping out the front doors of the Concordia Station often gives me the same feeling. Magnificent desolation. In the moonlight the vast expanse of Antarctic is humbling, and I wonder what happened to the desire to go where no men has gone before. 47 years later (44 since the last man said ‘goodbye’ to the moon), we have astronauts constantly flying in space but the moon is still very far away.

“We choose to go to the Moon! … We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.”

John F. Kennedy – September 12, 1962

I like to think of JFK’s words as I wonder what I’m doing here in Antartica. The question a lot of people asked me when I agreed to spend a year of my life in the middle of nowhere is all of a sudden quite real for me as well.

Why?

The idea of adventure and something so extreme was quite appealing when I applied over a year ago. Now the full magnitude of the task is more evident. I have a stronger understand of what true desolation can do to a person. It’s been almost six months since I said goodbye to the pilot of the last plane, since then my world only consists of 11 other faces. In such a small group, the smallest things can become big problems especially if you spend enough time together, and time here is not lacking. With each passing day, the thought of something new becomes even more exciting.

“WE NEED YOU”

As I take a urine sample out of the big brown bottle my colleague had used to store 24 hours of his urine production, I glance at the NASA poster I hung in my lab.“WE NEED YOU”. As part of the CHOICE experiment (a collaboration project between ESA and NASA), I take monthly blood, saliva and urine samples. I guess they really do need ‘me’. Who else will take the samples and check what the effect of isolation is on the immune system? When I tell my colleague his pee will actually help the understanding of what happens to astronauts on long missions to the moon and beyond, he just smiles and says that he is happy considering every bottle he hands in means another month has passed.

As I put the urine samples in between the two windows of my lab for a quick freeze before they go in storage, I notice the sky is quite blue today. Roughly three months have passed since the last sunrise. Only 10 more days before the first sunlight will rise above the horizon again. After months of darkness, the slow return of the blue light feels a bit like waking up. The hint of colour illuminates areas around the base and I can finally see the outlines of the summer camp buried deep in snow. In two month’s time the temperatures will be high enough to heat up the camp and start preparing for the summer campaign. New faces! Time for change.

Desolation. It’s possibly quite magnificent with some light again.

In the end, Buzz Aldrin was right. The Concordian life is almost the same as touching down on the Moon…

It just needs a little extra contact and more light.

Temperature -68.5°C. Windchill -89.9°C.

Discussion: no comments