I had travelled across the world to come to my new home, Concordia Station. Now I had to get to know the place, how things worked here, and find my place among its crew. They made up the whole population of my new world.

Inland Antarctica has no permanent human settlements in the form of towns or cities, only research stations where crews come and go. What draws people to this harsh environment is not gold or oil but something even more valuable: knowledge.

During the summer months, Concordia Station is a hive of activity, with the international scientific, technical and logistical teams busy preparing for the coming winter. Concordia can host about 60 people during the short summer period, both technicians and scientists such as astronomers, glaciologists, climatologists, seismologists and physicians.

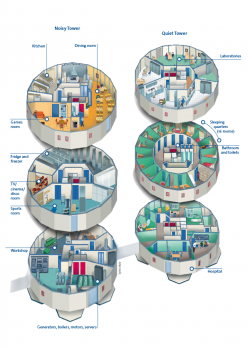

Built and operated by the French IPEV polar institute and the Italian PNRA Antarctic programme, Concordia is the only permanent European station on inland Antarctica. The site was originally selected for the stability of its ice, favourable for drilling into ancient ice cores that represent a treasure trove of climate recordings. The station consists of two towers connected by an enclosed walkway. One tower is dedicated to “noisy” rooms, such as the canteen, social rooms, gym and workshops. The other is the quiet tower containing sleeping quarters, hospital, laboratories and radio rooms. With its three levels the station is quite large: 1500 m2 for a maximum of 16 people during winter – nearly 100 m2 per person. A 15-metre-long seismic vault excavated near the station is used for experiments inside the Antarctic ice. Scientific instruments are dotted outside the station, including a number of telescopes. Still further away from the station, one of the tallest towers in all of Antarctica stands proud. This 40-metre scaffold construction, commonly called the American Tower, holds devices to measure atmospheric data such as wind speed and humidity. Many instruments at Concordia observe the snow and ice, and year-round tower instrument observations run by scientists on behalf of ESA help calibrate Earth Observation satellites, such as the SMOS orbiter looking into the Earth’s water cycle.

Preparing and launching the experiments I would lead soon kept me pretty busy, although winter would be the main period for running the research protocols.

[pullquote]“Concordia is a melting pot of personalities.”[/pullquote]

Working in Antarctica makes you feel part of something much bigger. The international nature of the station permeates everything. Concordia is a melting pot of personalities, from many different countries, professional fields and backgrounds. I enjoyed getting to know a wide range of people and spent a lot of time speaking with people from all the different groups. It was also great to have the opportunity to learn new languages. This summer there were Italian, French, Swiss, German, British and Spanish crew members at Concordia. I enjoyed learning about how different events are celebrated by the other nationalities. At Christmas, for example – which is during summer there – we helped an Italian colleague make Limoncello. On New Year’s Eve we were served frog’s legs and escargots. By sampling from each country’s heritage, we made up our own “Concordian” way, learning a lot in the process – and having fun.

During summer at Concordia there was not much privacy to be had. We shared our bedrooms with other crew members and the laboratories were typically full to bursting of people. All of the bunks had curtains though, which meant you could close the curtain and cut out the world, which could actually be pretty cosy.

So the station was far from quiet. Even walking outside of it came with an unexpected level of noise. The many instruments around the station were constantly humming and beeping, as if they were alive. Also, the snow crunched and squeaked loudly under my feet wherever I moved. My breathing was really heavy due to the thin air and quickly made my goggles ice up.

That said, there was something quite magical about the Antarctican landscape. It was so vast that everything felt still, epic and relaxing. The cold air was clean, without a trace of pollution. I felt much more in touch with the Earth, as the environment was not shielded from you as it often is at home, in say a shopping mall or a high-rise office building.

There were many new impressions, small things to be learned and rules to follow. It took some adjustment to get used to my new home, where rules turned out to be very different.

Take such a basic thing as water. Because Concordia recycles most of its water, we were only allowed to use special products in the shower. This meant no conditioner for over a year for me … But that was a small sacrifice, knowing that our water recycling machine was originally a prototype for the one astronauts use on the International Space Station. Testing under real-life conditions how to recycle a resource such as water is of direct use in developing the recycling systems for human spaceflight missions beyond Earth, where each kilo brought amounts to a heavy cost and replenishment may not be an option. ESA’s MELiSSA project has been working for over two decades to create self-sustaining ecosystems to support life indefinitely in a closed environment.

[pullquote]“A power failure would mean almost certain death for all crew unless the emergency source can be initiated in time.” [/pullquote]

Of course, energy is also precious. Concordia has a power station which is powered by fuel that travels about 1300 km from the coast to the station on an overland traverse using special snow trucks. The value of energy becomes all the more apparent as you think of the winter months, when a power failure would mean almost certain death for all the crew unless the emergency source can be initiated in time. We did an emergency exercise to simulate this and it took several hours to heat up the reserve engines. This is also why Concordia is built as two towers – one can be cut off from the other in case of fire, which maintains half the base for the crew.

Electrical power is also a special chapter. As the station is insulated from the Earth by the ice it is difficult to keep electricity stable. This means you often lose hard disk drives and electrical equipment. I got through three hard disks within my first month of being there. This is of course also relevant for the experiment data and it was really important to back everything up. The dry atmosphere also meant I regularly got a shock when I touched a door handle or another crew member. My hair regularly stood on end and floated around my head because of this. Often at night, when I moved my duvet, I could see the electrical charges set off.

Everything that reaches Concordia has made such an incredible journey that it is more important than ever not to waste things. All of our unavoidable waste was transported back out of the continent, so as not to pollute the Antarctican environment. This is a huge logistical challenge in itself. You therefore had to be very strict with the waste. We also sorted all of our waste so that it could be compacted and later recycled.

[pullquote]“It was strange to see how quickly money can become meaningless.“[/pullquote]

Another peculiar thing was that all our food and beverages were free, along with any other products for personal use, such as polar clothing and shower products. As a matter of fact, no one used money at the station. It was strange to see how quickly money can become meaningless.

Instead, personal things became more valuable, as they could not be replaced. I guess for me the thing of most value turned out to be my camera. I am a keen photographer and took many opportunities to go outside, although you had to act quickly as the camera could only take a few shots before it froze.

[pullquote]“With no shops around the corner, people started to get creative.”[/pullquote]

The other things gaining real value there were gifts from the other crew. With no shops around the corner, people started to get creative. A tinfoil penguin and a lampshade made from can ring pulls and stones were among my favourites.

This also means that there are normally no spares of anything around, however much you may need them. In Antarctica you cannot expect things to work like they would back home, so you have to be flexible and accommodating. The French just say “C’est l’Antarctique …” and I think this is a pretty good philosophy to have.

During the summer I spent a good proportion of my free time in the so-called EPICA workshop. The European Project for Ice Coring in Antarctica is a famous ice core drilling project, known for having drilled a three km deep hole to attain the oldest ice core ever recorded, at 800,000 years old. Their workshop was composed of a weather haven tent outside, with a small stove in one corner. Although simple, it was without doubt one of my favourite places. I enjoyed, as often as I could, to spend my time chatting to the EPICA crew, who had been coming to Antarctica for many years. Most of them had also worked at other Antarctic stations, like Vostok and Rothera, and had also gone deep into the inland wilderness on scientific traverses. So they had plenty of stories and anecdotes to tell. I love this aspect of Antarctica – the sharing of its history and adventures with international polar colleagues next to a little warming stove.

[pullquote]“By drilling down into the ice, you can effectively go back in time.”[/pullquote]

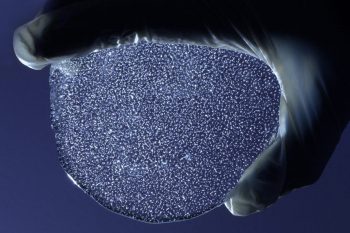

The EPICA team even let me drill my own ice core, which was a very special moment for me. An ice core functions as a kind of time machine. As yearly snowfall turns to layers of ice, bubbles of air become trapped. These tiny “time capsules” contain the gases and chemicals that were in the atmosphere when the snow fell. By drilling down into the ice, you can effectively go back in time, not hundreds of years, or even thousands, but hundreds of thousands of years… To ages when humankind did not even exist on Earth. Analysis of these ice cores shows clearly the major climate shifts between ice ages and warm periods, revealing the link between carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and the Earth’s temperature in the past. This information helps scientists make the distinction between changes linked to the Earth’s natural cycles and those linked to human activity. The ice thus functions like a huge archive of information on the Earth’s climate through many ages. Frozen and stored, the information is still there, if you can only get to it.

[pullquote]“Beneath the up to four kilometres of ice lies a hidden world …”[/pullquote]

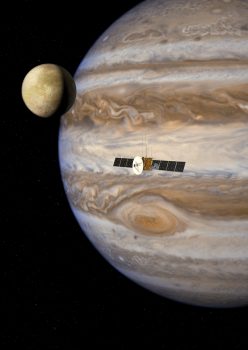

ESA’s JUICE (JUpiter ICy moons Explorer) will study moons of the Jovian system, some of which are believed to have subsurface oceans. Credits: ESA

Many secrets of our world’s history are locked in the ice, rocks and seabed sediments of Antarctica. Beneath the up to four kilometres of ice lies a hidden world of mountain chains, lakes and rivers. Such bodies of arctic water, unseen and untouched for hundreds of thousands of years, may contain microorganisms that would help us understand more about how life adapts to extremely challenging environments, and thus also about the possible existence of life on harsh planets and icy moons, such as Jupiter’s moon Europa. Satellites provide one means of revealing the hidden world beneath the ice, by probing the surface with sophisticated instruments from orbit. ESA’s CryoSat and SMOS orbiters each see through clouds and in the dark, providing continuous year-round measurements over these lands that are prone to both difficult weather and long periods of darkness. In this way, ice-covered lakes, rivers and even vast craters have been found and studied.

Summer was overall a very exciting time for me, with much that had to be learned, but most of it was so fascinating that it was a pure pleasure.

[pullquote]“I had been accused of ‘grounding the plane’.”[/pullquote]

I also enjoyed taking in the atmosphere of this very special outpost, getting to know as many people as possible, also those just alighting at the station with one of the aeroplanes. I particularly enjoyed taking a coffee with Jim and the other polar pilots and their Canadian crews. They told me about the places they had been and about their many adventures flying aircraft across the poles. There was one particular incident though, when I had been having coffee and a chat with them just as usual, but afterwards realised that almost the entire station was no longer speaking to me. This was because I had been accused of “grounding the plane”. The pilots had apparently lost track of time, caught up in our conversation, causing those expecting to take the plane that day to be delayed for a week. In actual fact, the plane left the following morning. But I had learnt first-hand how quickly stories and gossip can escalate in a small community like ours.

[pullquote]“Winter was coming, with its constant darkness and isolation.” [/pullquote]

The reason for the intense level of activity at the station was of course linked to the change of seasons. Summer is a short window that must be used to the fullest in order to prepare for the other much more challenging months of the year. Everyone knew that winter was coming, with its constant darkness and isolation.

I heard many stories about the crews of previous winters – some of them wildly exaggerated, I am sure. Still, it made me nervous to consider how I would personally react to the coming experience and what challenges we would face as a crew.

For with all the small talk there was also an increasingly perceptible undercurrent of seriousness. People belonged to two categories. The majority would leave before darkness descended and cut off all transportation links. And then there was the small group of thirteen people who belonged to the overwintering crew, which included me.

[pullquote]“Everyone at the station had an opinion about how our winter would turn out – and most felt compelled to share it.”[/pullquote]

Everyone at the station had an opinion about how our winter would turn out – and most felt compelled to share it with those of us who would stay on. Intermingled with this were also many stories about people in our crew, some true, some certainly not. Gossip at the station was unavoidable.

At a few points during the summer period I did consider my decision to come there, and if it was indeed the right choice for me. The approaching day of “no return”, when the last plane would leave and I would be facing nine months with just twelve other people, gave me some anxiety. What if I had made the wrong decision? The most frightening aspect was not the lethal cold outside, but the isolation inside and how we would react to it – me included.

As that last day came, I said goodbye to some of the closest friends I had made during summer. I also bade farewell to Jim and the team of pilots I had so enjoyed spending time with. It was quite an emotional time for me. But the planes had to leave.

I still remember the sinking feeling as the noise of the last aircraft died away as it disappeared from view. Everything went quiet. Torn and forlorn, I went back inside the station, intent upon facing down the coming winter. Back in my bedchamber I looked at the calendar on the wall. The days until the next plane would arrive appeared endless.

At least I no longer had to worry about choosing to stay or not. It was too late for that. Only one thing was certain: I would face the longest and coldest winter on Earth, all of it here at Concordia, as part of the winter crew.

Discussion: 3 comments

I am surprised that in this day and age that the emergency back up generator system is so archaic. In all my days at sea and in power plants (40 years) emergency systems were ready for immediate use. Not withstanding that the environment the station is located in is one of if not the harshest on earth, it should not take hours to bring emergency equipment online especially when it comes to the safety of personnel. There should be heaters installed in that equipment that keep it at nominal temperature for operation.

I’m interested in comments about the lack of an adequate “Ground” (American) or “Earth” (British) connection. I wonder why they haven’t created something like the PME (Protective Multiple Earth) that we have in residential streets.

I believe that often there is a slight potential difference between PME and Earth, but except with radio equipment the Earth (Radio Frequency (RF) Earth) and PME is effectively the same. (I have a radio ham setup which uses Earth against the antenna).

So I wonder if this is why it takes a long time to kick in the emergency system, if everything is at a different potential to each other?

Thanks Beth, I’m really enjoying your story….can’t wait for the next chapter! Please talk to ESA about joining the Space Medicine Cadre. It is a blast taking care of the astronauts – I think you would fit right in. Maybe it’s your next great adventure!