As the plane roared off from Paris Charles de Gaulle airport, I realised with excitement and a little trepidation that our Antarctic adventure was finally taking off as well.

We flew down via Singapore to New Zealand, in order to approach Antarctica after a last stop for supplies and final preparations. Arriving in Christchurch, we were quickly taken to the International Antarctic Centre, where we were briefed on safety protocols and the flight procedures. I watched a few tourists being driven around in the Antarctic trucks at the museum and imagined that in less than 24 hours I would be driven in them on the Antarctic ice for real.

[pullquote]This was our final chance to get any last minute supplies. I bought only flip-flops.[/pullquote]

This was our final chance to get any last minute supplies. I bought only flip-flops. Not the most obvious essential for life in Antarctica, but I thought they would come in pretty handy for life in a research station.

We now departed in an impressive Hercules plane towards the Italian Antarctic coastal station Mario Zuchelli. The plane crew kindly invited me to join them in the cockpit. I enjoyed watching the sea gradually turn to ice as we approached the vast frozen continent. Seeing the ice spreading its domination over everything around us was quite impressive.

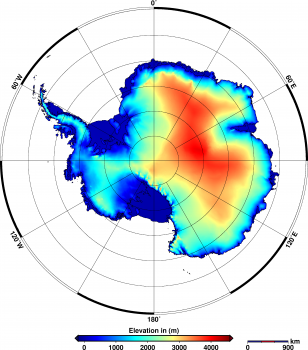

The Antarctic ice sheet is the largest single mass of ice on Earth, holding approximately 61% of all fresh water on this planet. This is an amount equivalent to about 60 metres height of water in the world’s oceans. The sea water chilled by the ice affects ocean currents and thereby influences temperatures around the world. The ice also reflects sunlight back into space, which helps cool the planet. If the ice were all to melt, the oceans would flood major parts of the Earth and highly populated coastal areas. Assessments of changes in polar ice mass help scientists predict sea level rise and climate change. Satellites are perhaps the best way to measure the ice as they can survey these vast, remote regions continuously from space. ESA’s CryoSat II satellite, for example, is dedicated to measuring fluctuations in the thickness of ice on both land and sea. Other Earth Observation satellites, such as the ESA-developed Sentinels, help to map the height, extent and movement of the ice. Indeed, sitting in that plane with only ice below us and empty sky above, I realised why satellites were so crucial to monitoring these huge areas.

[pullquote]With only ice below us and empty sky above, I realised why satellites were so crucial[/pullquote]

Before long the continental landmass and its coastline became vcisible before us. At its edges, ice flows off the land to form massive floating ice shelves which end in steep ice cliffs. Enormous icebergs calve off from these ice shelves and float away in the seas surrounding Antarctica.

I was lucky enough to be allowed to stay in the cockpit for the landing at the coastal station and watched in awe as we touched down smoothly onto the ice runway. We had arrived at the entrance to this frigid world.

Our group was quickly loaded into a van and transferred into a much smaller Basler plane that was waiting on the ice, ready to take us into the Antarctic continent and to Concordia.

In contrast to the large Hercules plane, the Basler felt very vulnerable and small as we took off for our final destination. Fortunately, we had just the right pilot and crew to reassure us – Jim and the Kenn Borek Air Crew. They are real legends of Antarctica, flying operations all over the continent, for scientific expeditions, ambulance service, and more. Jim is one of the longest serving pilots for the airline and had by this time visited most stations of the continent. A bond was immediately established between us and this would be the start of a friendship I would come back to during my time there.

As we flew in over the mainland, the full magnificence of the place became obvious. As Scott, the polar explorer long before me, had put it in his journals, Antarctica “satisfies every claim of scenic magnificence.” He was right.

Compared to the enormity of Antarctica it felt like our aircraft was nothing more than a fruitfly, lost far from home. I spent most of the journey trying to de-ice my window, to catch better glimpses of the vast Antarctic plateau as we made our way towards Concordia.

We had entered above the plateau called “Dome C”, in height comparable to many mountains of Earth, at around 3200 metres. Antarctica is the highest continent on Earth. This is due to the ice accumulating on the solid ground in a way not found on the other continents. And beyond, to the west, I knew that a massive mountain range – the Transantarctic mountains – cut through the continent, their peaks often hidden in cloud and white haze. They rise from sea level up to 4500 metres, while further northwest another mountain range, the Ellsworth Mountains, reach even higher at almost 4900 metres.

These peaks and the desolate lands around them have inspired the world’s greatest authors of horror and adventure fiction. Credits: British Antarctic Survey

These peaks and the desolate lands around them have inspired the world’s greatest authors of horror and adventure fiction, from Edgar Allen Poe to Jules Verne and H.P. Lovecraft, the last envisioning them in his At the Mountains of Madness. Maybe it is the alien and so mysterious nature of this continent that inspires artists and explorers alike. For still today, here are untrodden paths and places where no human has ever set up camp. It is the only place left on Earth with vast areas that have never seen human presence. I felt a tinge of suspense, realising I was following in the wake of the polar pioneers who had braved the partly unknown continent before me.

[pullquote]It is the only place left on Earth with vast areas that have never seen human presence.[/pullquote]

Naturally, there is no real infrastructure to be found outside the stations scattered over this empty land. We would be on our own down there. From ESA I had heard that the facilities in the polar regions are increasingly reliant on an array of space infrastructure for their operations, such as for telecommunications with the outside world or for help in navigation and observation. Looking out over the white scenery it was easy to see why satellites would be needed – there were no signs of civilisation anywhere.

[pullquote]This polar region is so remote that even satellites seldom pass over it.[/pullquote]

In fact, this polar region is so remote that even satellites seldom pass over it. When ESA’s GOCE orbiter measured the Earth’s gravity field with unprecedented resolution, regions of Antarctica were never crossed. To fill the data gaps it was necessary to launch an international mission, called PolarGAP, making use of innovative gravimetry, radar and Lidar measurement systems deployed on an aircraft. Mapping the Earth’s gravity field is done for a wide range of applications, including geodetic studies (levelling and mapping), satellite navigation and measuring the impact of climate change on ice sheet mass. The Antarctic ice sheet measurably affects the gravity field of Earth. In fact, loss of ice from West Antarctica between 2009 and 2012 caused a dip in the gravity field over the region.

Sitting there looking out of my window, lost in my thoughts, I was surprised when our plane suddenly started to descend. I could not see anything for us to be landing on. There was just the plain white landscape as far as the eye could see, even from high up in this aeroplane.

“Why are we descending?” I shouted out to Jim and the crew above the noise of the motors, but no one seemed to notice as they were already getting ready for landing.

The plane went down quickly and I realised that we would touch ground here on the ice, seemingly in the middle of nowhere. Well, I should not have expected an airport … The plane bumped and veered as we made contact with the ice runway, but the pilot had it all under control and soon we were rolling forward with moderate speed.

It was only when the plane turned a corner off the ice runway that I caught my first glimpse in the distance of the iconic twin towers of Concordia Station. But in this landscape of overblown proportions they were just two specks, black against the otherwise untouched white horizon.

As soon as the plane had come to a halt, the door swung open. Cold air hit me like I had collided with a concrete wall. My lungs constricted as I tried to catch my breath. Iced, goggled figures completely covered in polar garb that made me think of space suits, entered the plane. They helped me get up and get my bearings, then out of the plane.

Stepping out of the plane was like stepping out on another planet. The purity and vastness of the never-ending ice landscape all around made me feel very small. I was like a visitor from another world. Despite my garb and preparations, within just a few seconds of being outside I was literally being frozen. I felt the inside of my nose start to ice up, the moisture in my eyes start crystallising, any uncovered strand of hair stiffening.

There is a reason Concordia is often referred to as “White Mars”. There are no penguins or seals there, no native animals, let alone native people. The bright light of the 24-hour Sun reflected off the snow is blinding. My laboured breathing was not out of physical exertion, but caused by the high altitude – as if we had been up on a summit of the Alps. Except for our group, the place was completely still and ghostly silent.

[pullquote]Stepping out of the plane was like stepping out on another planet.[/pullquote]

As I made my way across the snow towards the entrance to my new home, I would have opened my mouth to ask the question, but decided it was not worth freezing my tongue as well.

So this is summer here?

Discussion: 2 comments

Thanks for the reminder that we get one go at this world , I was on the Imagineering stand next door to your dome at Malvern . Keep pushing your boundaries .

This is really well written! I hope someday you’ll consider writing a book about your experiences. I reckon it could be a best-seller!