When winter comes to Concordia you’d better be prepared. Before us were nine months of complete isolation, four of these in constant darkness as the sun would never rise above the horizon.

[pullquote]This was the last sunset – or sunrise – we would see in four months’ time.[/pullquote]

It was a busy time for me in the lab since the last plane had left. All of the ESA experimental equipment had arrived so I had to set up the experiments and start the protocols. My best way of dealing with the suspenseful waiting for winter was to focus on my work. The days quickly got shorter and shorter, the light itself was failing as the sun was slipping away. The scenic beauty of the landscape around the station faded as the season steadily and inexorably turned from intimidating to deadly. More and more I actually wanted winter to start. The sooner it starts, the sooner it finishes.

And soon enough we looked out of the window towards that last sliver of sun on the horizon, knowing that this was the last sunset – or sunrise – we would see in four months’ time. Not only winter was here, but night as well.

Our overwinter crew was composed of thirteen people. Good that I am not superstitious. We were four women (me included) and nine men. Six were French, five Italian, there was one Swiss and me, the Brit. Also when it came to age, educational and socio-economic background there were quite some differences. But we would have to work closely together as a team to get through winter and all the scientific experiments in the best way. As we were a “skeleton” crew, all the team members were required to take on different roles. For example, the plumber was also trained to assist in the operating theatre, while the chef was also a fireman. A similar model would also be needed for long-duration spaceflight missions, which was no coincidence of course.

[pullquote]All of the crew were given activity watches to wear at all times. [/pullquote]

The way the crew members interacted with each other, forming groups or spending time alone, was relevant also to one of the experiments I had to conduct. All of the crew were given activity watches to wear at all times. These monitored not only personal activity levels, heart rate and sleep patterns, but also the interaction with other crew members and location in the station. Each watch was able to detect who you were in a room with and where in the station you were. This would make it possible to monitor how relationships changed among the crew. It would also look at habits and detect changes in preference for social versus private areas, or time spent working or doing other things, such as going to the gym or the kitchen. The watch would know how long you spent interacting with anyone. And we were indeed going to see changes in our behaviour during the coming months of isolation.

The experiment even went further, to check whether spending a year at Concordia physically changed connections in the brain. This was done by performing brain scans on us before and after the stay. Elements of this experiment had also been done by astronauts on the International Space Station and during the Mars500 isolation study run by ESA and the Russian Institute of Biomedical Problems.

Another of my experiments, to monitor the mood of the crew, was the so-called “video diaries”. Knowing how someone feels can be a life-saver for mission controllers planning a space-walk or spacecraft docking. But ask anybody how they feel and most will reply “fine”. Looking at external signs is therefore a more efficient way to assess mood. The experiment let crew members regularly record a video diary of their life at Concordia, as well as narrate a paragraph from a fairy tale. By looking at changes in the way they talked to the camera and comparing these with results from standard questionnaires, researchers would try to develop software that could analyse speech automatically. Also recordings from our social conversations at the dinner table were used for this purpose.

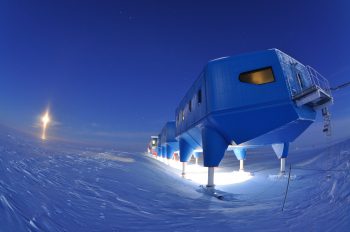

A novelty this year was that some of the experiments were extended to another research station so that data could be compared between different places. ESA was therefore cooperating with the British Antarctic Survey and its Halley VI station situated on the other side of the Antarctic continent. The crew at the Halley station were experiencing the same isolation and lack of daylight as we were, but they lived at sea level, close to the coast. Performing the same investigations at Halley would therefore allow researchers to cross one factor off the list that might influence the data: air pressure.

This comparative set-up was used for an experiment to test how our eyes adapted to months of outside darkness and only artificial light, and whether this environment affected sleep. This experiment could benefit not only astronauts, but many people who spend a lot of time in low-light environments, such as night shift workers, insomniacs and people with eye problems. Knowing that these experiments were being conducted simultaneously at BAS’s Halley station 3146 km away was intriguing and motivating for me. I had been in contact with some colleagues based there, such as my equivalent at Halley, medical doctor Nathalie Pattyn, and overwintering science engineer Alexander Finch.

Not all my experiments were carried out inside the station. For the “Bacfinder” I had to go outside a number of times, regardless of outside conditions. Concordia is situated on one of the most barren places on Earth. This experiment was set to find out if life, such as bacteria, fungi and viral colonies, could have adapted to this extreme environment. Such life might have arrived there on its own or travelled inadvertently with crew members. I was therefore to collect snow samples and take supplementary meteorological measurements. The samples would then be cultivated in the lab.

Sometimes temperatures outside were as low as -80C and I had to work in complete darkness. The first time I went outside to take samples I found that the glue on my notebook immediately froze and disintegrated, the glued seams of the plastic bags opened up and my pen did not write properly as the ink froze. Not to mention that the equipment I used to collect the meteorological data ran out of battery before I could take the measurements (batteries run out very quickly when they get cold). I abandoned the sampling that day and returned later with a revised strategy.

[pullquote]My hands would start to get really cold. This was in spite of me typically wearing three pairs of gloves as a minimum.[/pullquote]

We set up heated shelters at close distances to each other around the station. This meant I could “hop” between the shelters in order to stay warm and safe. But I would not call that warm … I normally took ten samples at each location. By sample number seven my hands would start to get really cold. This was in spite of me typically wearing three pairs of gloves as a minimum. Some dexterity was needed to take the samples, so I would just remove the outer mitt, but despite all the protection my hands were still going numb.

A view from the top of the “quiet” tower of Concordia during winter. Credits: ESA/IPEV/PNRA–B. Healey

There was something surreal about going out in the Antarctic night, on a mission for a space agency, to search for life forms hidden in the ice, maybe even unknown forms of life. Like many in my generation I had watched films about what Antarctic scientific crews might find in the ice – in particular The Thing came to mind. This was sort of the real life equivalent … Seriously though, I found this experiment particularly fascinating. Finding bacteria able to survive under these conditions could perhaps mean that they could also survive on planets or moons with similar conditions, such as Mars.

[pullquote]Finding bacteria able to survive under these conditions could perhaps mean that they could also survive on planets or moons with similar conditions.[/pullquote]

ESA has a long history of studying strange life that can survive in the most barren places. Tardigrades and lichen taken into space for ESA experiments without protection have survived and continued to live subsequently on Earth. In 2014, scientists from the British Antarctic Survey and the University of Reading announced that they had successfully revived mosses that had been frozen in the permafrost of an Antarctic island. They placed the moss in an incubator at 17C, and after a few weeks, without any particular intervention, the moss started to grow again, after having spent a whopping 1530 years frozen in the ice. Such findings open intriguing possibilities that, in the right circumstances, multi-cellular organisms such as plants can survive for longer timeframes than previously thought. Antarctica is such a harsh environment, even around the coast, that life has had to adapt in many remarkable ways in order to survive. Antarctic cod, for example, have a special “anti-freeze” protein in their blood that stops them from freezing up completely. In fact, we can learn a lot from organisms that can live in extreme environments – space mission designers even consider using such micro-organisms for human purposes in future space travel.

[pullquote]The moss started to grow again, after having spent 1530 years frozen in the ice.[/pullquote]

Some of the experiments turned out to be challenging in much more mundane ways. If you run out of any equipment during winter it is impossible to replace it until the next plane arrives. For one of the experiments we ran out of blood bottles, so these had to be flown in on the first plane during summer. Something so cheap and simple can quickly become the decisive factor for a whole experiment. Therefore everything has to be meticulously prepared, checked and rechecked and plenty of spares sent over in the first place.

The participation of the other crew members was crucial for most experiments, but was on a voluntary basis. I was therefore constantly asking the other crew for their participation. When the novelty wore off and the night grew long it became more and more difficult to motivate the crew to continue. But regular continued participation was one of the most important aspects, as I often monitored the – often subtle – changes over time, which would easily be lost with missed data points.

Focussing on the scientific work was one way for me to try and get through the constant darkness. But over time I felt that I was losing my energy and getting tired. People became whiter, pasty and gaunt. The atmosphere at the station became more tense. I also started to have problems with my sleep, spending whole nights awake wandering the station alone. These were the moments when I felt lonely. I looked out of the window to face only a dark void, while the rest of the station slept. There were no street lamps, ambulances or cars passing by in the night to remind me that I was not alone in this world – just silence and emptiness.

Overall I needed more sleep than I did back home. It felt like my body was slowly falling apart during the polar night and that I needed the extra sleep to allow my body to recover and put everything back together again.

[pullquote]Without the sun, Concordia really did feel like a different planet.[/pullquote]

Without the sun, Concordia really did feel like a different planet. “White Mars” as it is often called, or perhaps one should say “Dark Mars”. In some way the sun had made me feel connected to the outside world. The sun, at least, was the same as back home, and this gave me a sense of familiarity. Losing that made me feel cut off, in a different world. The sun also gives you energy, especially in the morning. Without it I felt like I was working on a continual night shift.

It felt like my body went into a state of semi hibernation.

Eating also became difficult. Any dinner felt like I was trying to eat a five course meal in the middle of the night. Also, although our chef was both very skilled and creative, we were limited in our supplies. All of the food was dried or frozen (yes, kept frozen outside, naturally!) and I dreamt of fresh fruit and vegetables. But avocados and mangos were not to be found on the Antarctic plateau.

It was compulsory to attend all meal times to ensure good communication and team cohesion. Sometimes I felt like cooking something simple and eating on my own, but this was not possible.

During winter the language barrier also became much more noticeable to me, as I was the only English native speaker in the overwintering crew.

[pullquote]Any dinner felt like I was trying to eat a five course meal in the middle of the night.[/pullquote]

The lack of privacy, living isolated in such a small group, started to become difficult and engender conflicts. I felt not only that my actions were under constant scrutiny, but also that I was under constant attack and criticism. Even small things such as taking some cereal in the middle of the day were often commented on, as it could “ruin my dinner” or be “unhealthy”. With time this constant surveillance became frustrating.

Still the station felt really large during the winter. Unless you arranged to meet people you would rarely bump into the other crew members other than at set mealtimes. If I wanted, I could stay alone in the lab, but loneliness would become an issue.

Without at first realising it, I lost a lot of self-confidence during this winter. Deprived of interaction with new people, I became more nervous about speaking with people outside of the crew on our communication system. Even towards my friends and family on occasions. I worried I had become someone different.

Discussion: 6 comments

Thank you for an amazing “diary” of life in Concordia. My imagination had free reign and I felt I was actually watching a FILM of your months there.

main slot sekarang bisa pakai pulsa xl dan telkomsel loh, silahkan kunjungi http://jakartapoker.co/ untuk informasi selengkapnya, tersedia cara depositnya juga loh.

Anda yang suka dengan tim tim sepakbola Inggris dan ingin mendukung mereka yang brrtanding dapt mengunjunig http://mahaloactionsports.com/agen-judi-sbobet-terpercaya-yang-menyediakan-pasaran-liga-inggris/ dengan minimal deposit murah IDR 25000.

Main judi bola online di agen yang tepat yaitu taruhan sbobet bettor cuma perli modal 25rb aja untuk deposit, informasi lebih lanjut klik disini http://banjirhoki.xyz/daftar-agen-sbobet-terbaik-tahun-2020-rekomendasi-bettor-pro/

Tidak ingin kalah dan rugi lagi saat main judi bola ? langsung deh klik link berikut ini http://jackpotbahagia.com/agen-resmi-sbobet-di-indonesia-sudah-berpengalaman-belasan-tahun/ karena ada agen sbobet yang asli Indonesia mudah dimenangkan

Sudah ingin segera main game slot online tapi bingung mau main di situs yang seperti apa? coba cek artikel ini sekarang juga deh! http://dewaslotmpo.com/situs-slot-online-terpercaya-2020-1-id-bisa-main-sepuasnya/