ESA-sponsored medical doctor Floris van den Berg recounts how he prepared for his year-long stay in Concordia on his blog and explains why living in Concordia can be breathtaking.

Concordia Station is effectively located 3800 meters above sea level, so the phrase ‘out of breath’ is the number one answer you get when asking people how they feel when they first arrive.

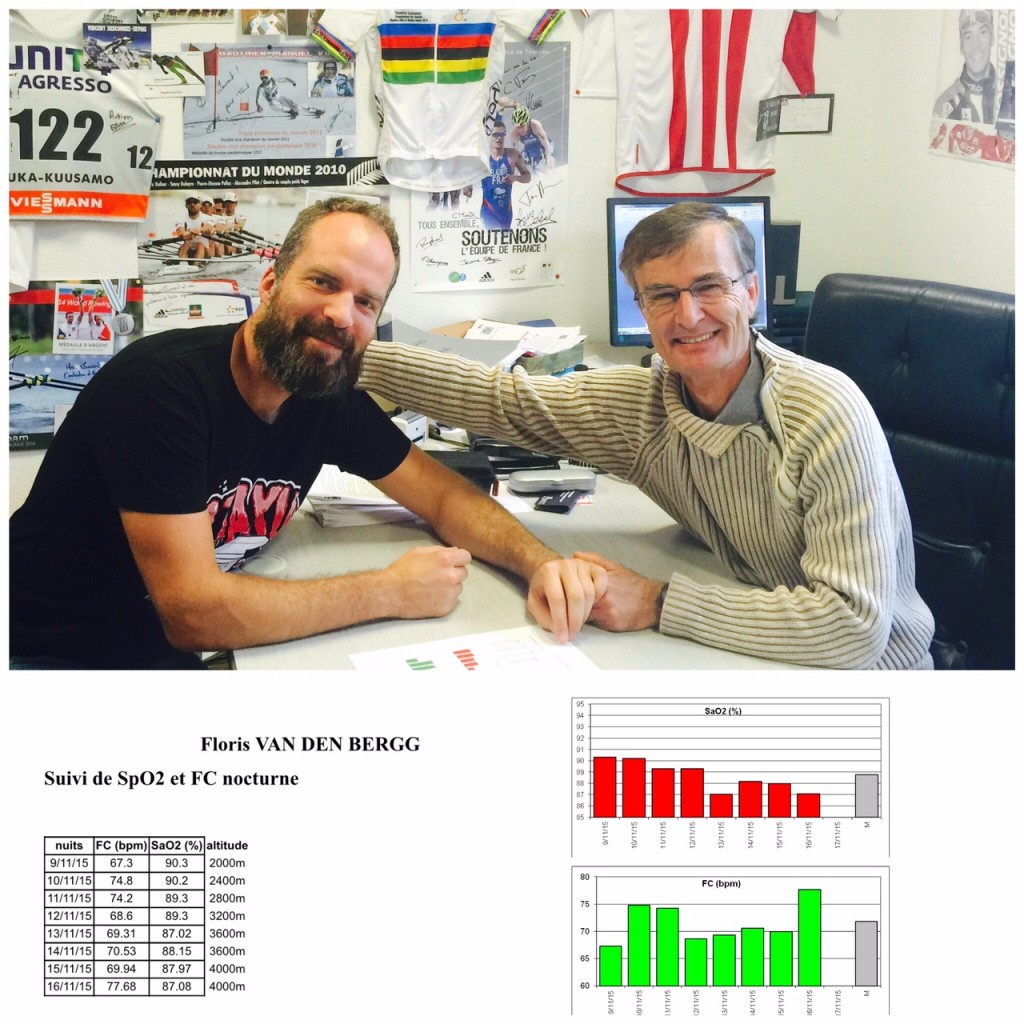

I want to feel ‘pretty good’ instead, and headed to the National Centre for Nordic and Mountain Skiing in Prémanon, France for altitude training. There I met Laurent Schmitt, an expert in sports performance and altitude training with an impressive resumé including years of training for the French national sports selections, I was happy to meet him and discuss the optimal preparation for my year at altitude.

Credits: ESA/IPEV/PNRA-F. van den Berg

So why do we have such a hard time breathing at altitude?

In our ‘normal’ life, at sea level, there is a column of air pressing down on us, which is comparable to the pressure of 10 m of water. The higher we go, the smaller the column and lower the amount of pressure we feel since less air to press down on us. This means that the density of the air is lower at higher altitudes.

Due to the altitude and location close to the South pole, the density of the air in Concordia Station is roughly 30% less than at sea level. So with every breath you take, your body is getting 30% less oxygen than at sea level.

The body responds to this by breathing faster and trying to adapt by increasing its compensation mechanisms. Slowly, the body will adapt to the lower oxygen levels by increasing the amount of red blood cells and changing internal pressure. In the BONE study, I will be checking for these changes and will track the changes in body composition and the blood to see how we adapt.

But what can we do to make life nicer in the meantime?

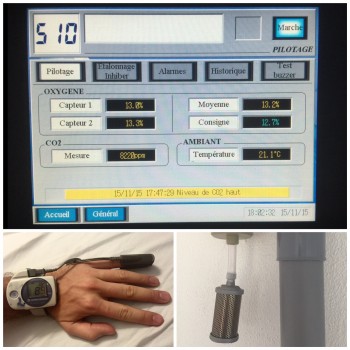

This is where Laurent Schmitt steps in. In Prémanon they built hermetically sealed rooms where an de-oxygenizer lowers the oxygen level in a controlled way. By slowly lowering the oxygen level, the body gets more time to adapt and suffers less. I definitely want to “suffer less”, so for a week I stayed in these rooms for at least 16 hours a day with the oxygen levels going down slowly to give my body more time to adjust.

During my week in Prémanon, every day the level of oxygen was set to a lower level, from the normal 21% to the 12,7% at 4000 meters. With a special finger monitor to measure the oxygen levels in my blood, we tracked how I responded to the decreased oxygen. After one week I feel ready to go, so with just a few stops in Frankfurt, Singapore and Christchurch I will be in Concordia in two days to test the theory!! Wish me luck!

Discussion: 3 comments

Thanks to share ! Good luck ! we’ll follow your adventure

Just out of curiosity, who’s rainbow jersey is it on the wall in the last picture?

Hi Valdis, I’m sorry but can’t help you with that one. After years and years of training he had an impressive collection of shirts on his wall. Try contacting Laurent Schmitt if you really want to know!