In space as on Earth, everything starts with a dream, or in this case a team of dreamers.

“Almost 10 years ago, a few colleagues and I thought that it was our responsibility as space actors to clean up space from debris” says Luisa Innocenti, head of ESA’s Clean Space office and a physicist by training. “We spent the following years in dreaming about launching a mission to remove a large non-operational spacecraft from orbit. Now finally this will happen. In 2025, ClearSpace-1 will become the world’s first mission to remove an item of debris from orbit.”

In 2013, the Clean Space office was officially established, with the objective to “guarantee the future of space activities by protecting the environment on Earth and in space”. Among other tasks, the Clean Space team had the mandate to:

- develop technologies for space debris rendezvous, capture and reentry

- place European industry in the forefront position of anticipated future markets.

Finally, space dreamers had an office and a mandate to go to work!

To begin with, the team decided to check if a try-out mission for space debris clean-up was indeed the way to go.. Was it an accurate assumption that that “it takes a space mission to catch a space mission”? To check that theory, they staged a debate on the subject at ESA’s Concurrent Design Facility at ESTEC. Two teams of space experts had to champion opposing views, overseen by a chairman.

“To IOD* or nor to IOD” that was the question.

The debate set the stage for follow-on studies on the – at the time called – e.Deorbit mission study concept.

A few months later that same year, ESA issued an Invitation to Tender to perform a ‘Phase A’ pre-development study to develop a space debris removal mission, known as… ‘e.Deorbit!

Six months later, in mid-2014, the Clean Space office organised the e.Deorbit Symposium. The event covered topics on studies and technology developments related to space debris remediation.

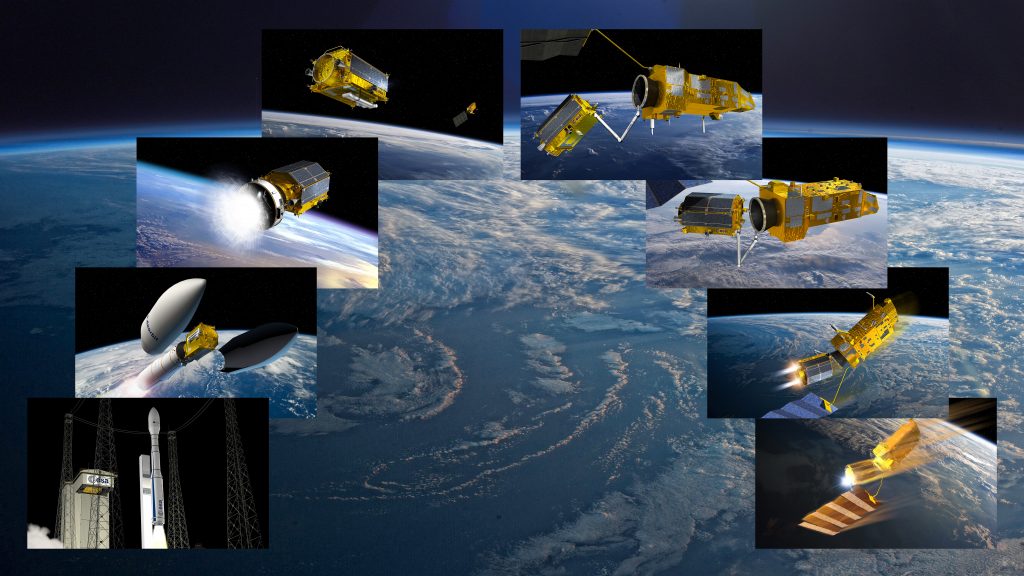

The e.Deorbit mission profile is quite similar to the ClearSpace-1 mission with some slight differences such as the choice of the target. At the time, the concept studied the removal of a debris item at the size of a bus, totally uncontrollable, and with lots of unknowns such as its spin rate.

.

The e.Deorbit mission profile with a robotic arm

The e.Deorbit mission profile with a net

The fact that the mission concept was so challenging pushed the engineers to design a robust, super-efficient and reliable Guidance, Navigation and Control (GNC) system and capture technologies.

Since then, ESA carried many studies with the hope to launch one day a dedicated debris removal mission. Among others, they investigated:

- the potential of optical and radar satellites in nearby orbits for space-to-space observations (to check the state of the spacecraft and understand its tumbling)

- sophisticated imaging sensors and advanced autonomous control (to estimate the orientation and position of the chaser relative to the target satellite)

- capture mechanisms with the goal to identify the one with the lowest risks during capture and the highest potential for reusability

- the best ways increase the level of coordination and synchronisation between guidance, navigation and control and robotics (to catch and stabilise a tumbling satellite).

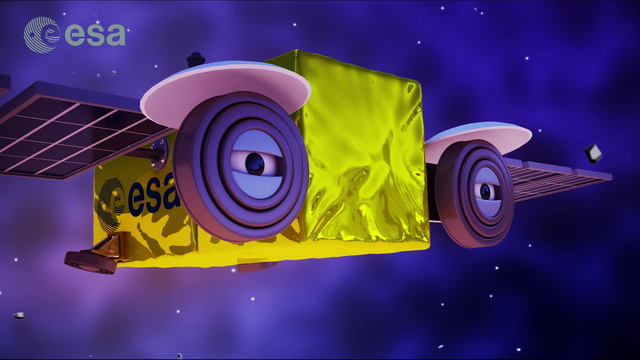

Finally the results of all this work paid of. At the last Ministerial, ESA received the needed funds to purchase the world-first debris removal mission ClearSpace-1. ESA Clean Space team has now the eyes on the year 2025 when the first flight of an in-orbit servicing mission will take place and will take down an item of debris.

And Robin Biesbroek, former e.Deorbit’s study manager, was proven right when he said in 2018 that “the main challenge [of removing a large piece of item] is not technical – it is to get the money”.

The team is also already looking past 2025 as they are already working to develop in-orbit servicing (IOS) technologies with the aim to lead the IOS market.

*IOD = In-Orbit Demonstration

Discussion: 4 comments

Congratulations, well done. I follow you with interest. Now the challenge is to combine the institutional activity and the private initiative so as to enable a commercial market of ADR and IOS.

You have well developed one of the main space-business of the future! Let’s get the leadership of this market for Europe! 2025 is the beginning only, the best is yet to come!

Insightful article. Thanks !

I am sure this has already been thought of, but, can an electrically activated magnet (on an arm maybe) be used during the missions to attract ferrous based metal fragments and drag them next to the atmosphere (turned off at that point) so they can burn up as they descend? Or is there enough ferrous based small fragments to be worth the cost?