Erwan Matton

This post has been written by Erwan Matton, stagiaire within the Clean Space team from 1st of May 2016 to 31st of August 2016.

Erwan is a 24 year-old student at ESTACA, a French engineering school for space and automotive techniques. He should graduate end of 2017. Among other tasks such as updating Clean Space roadmaps, we asked him to give an overview on space debris in a comprehensible way.

This is his article and we hope that you will not only enjoy the reading but learn a few things.

The Clean Space team

—————————

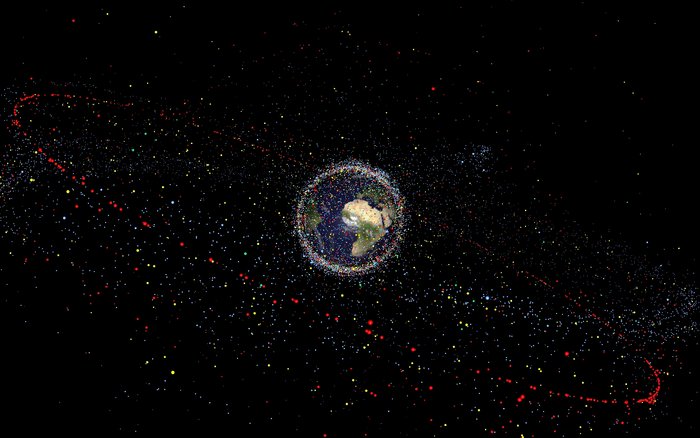

In the Clean Space initiative, we talk a lot about space debris: how many they are, where they are, why they are so pernicious, how to avoid the creation of new ones, how to actively remove some of them… 29000 items, both dead and operational, larger than 10 cm are orbiting the Earth , mostly located in low-earth orbit (up to 2000 km) and geostationary (36000km) orbit. But do you really know what these items are?

Floating space debris around the Earth

Credits: ESA / Marianne Tricot (Ecole Estienne Paris)

The experts of this issue have given a definition:

Space debris are all man-made objects, including their fragments and parts, whether their owners can be identified or not, in Earth orbit or re-entering the dense layers of the atmosphere that are non-functional with no reasonable expectation of their being able to assume or resume their intended functions or any other functions for which they are or can be authorized”. (Technical Report on Space Debris in 1999 by UN/COPUOS/STSC)

If you have to remember two things only, make sure they are the following ones: “all man-made objects” and “non-functional”! Hence, this means that a space debris can be anything, from a little screw to an entire derelict satellite. To make things clear, debris can be: non-functional satellites, launcher upper stages, fragments or pieces of satellite.

I mentioned satellites. Then you might wonder: “why does a satellite become a debris?” This is a very good question. The answer is pretty simple. Until now, nobody really cared about the destiny of the satellite after the end of the mission. Well, actually this used to be true, but this has been changing for the past few years. Anyway, most of the satellites are used until they are non-functional. This means until they don’t have any more fuel to follow their nominal trajectory, or that a failure occurred. From this moment, the satellite becomes a space debris, orbiting around the Earth, and no more action can be performed. Not even to avoid another debris! Today there are 3600 satellites in orbit, less than a third are operational. This means that 2500 debris are dead ones.

And what about the other debris, all the fragments? First, as mentioned before, there can be collisions. In LEO (low-earth orbit), the orbital speed is around 7.8km/s. The collision speed is more than 100 times higher than the one of two cars crashing into each other. In 2009, the collision between Iridium, an American operational satellite, and Cosmos, a Russian derelict one, created 2200 new debris. Another thing that can happen is the explosion of the satellite. The leftover fuel or batteries inside the old satellite could explode with the exposition to the intense orbital sunlight. The very same thing can also happen to upper stages, but now they have to passivate (it means to deplete themselves from their energy sources). One figure shows how important this is: 700,000 items of debris larger than 1cm are estimated to be in orbit

Another important fact is that reactivate a debris is not possible. It is like for humans, you don’t raise from the dead. Anyway, it is still possible to reduce the population of debris. Scientists estimate that 5 large objects per year can stabilise the environment once full mitigation is in place (For further information about mitigation measures, read about the CleanSat programme). The ESA’s e.Deorbit mission will be a first step with the removal of one of the biggest ESA’s debris.

Discussion: 3 comments

Nice post. Did not know about the 2009 or better, I heard but did not imagined it like I am going to picture to all of the readers now: the 2009 collision is like a environmental catastrophe, even if we are in Space Infinity it doesn t mean I am forcing it to think it like this.

It is a environmental tragedy like Alaska or Louisiana Spills Cernobyl or Fukushima. We might think to create “temenos” (sacred areas), No fly zone space areas but it would be a failing Idea to do so.

What we should do is start assessing this a crimes, and anyway since surely it can harm humans flying in space and even on Earth or on planes (very randomly – would be interesting to calculate with the future soild human density and the sharply raising flying traffic, what will be in 5 and 10 15 years the chances a plane can be hit and so causing death of hundreds of ppl.)

Besides this dark matters issues ;) we should grow a new concept of heritage in Space as these debris represent a huge value for future as thry become archeological proofs of paceful cooperation and competition between countries to discover unknown seas and explore reasearch and progress (of humanity). We shall not destroy even when we will bring back these items.

World should be disseminated or maybe even moon and mars should be disseminated with these items (anyway a project or more than one should be brought to the main stream, besides the cost entailed by this attitude, to recover, stock, show and communicate these values.

Space debtis are common heritage and not only area a threat but they represent a huge opportunity in many different ways. I consider the cultural opportunity, planetary opportunity the highest one because of its effects, power to change mentalities of humanity and individuals to inspire, educate with a “simple” archeological artifact of the modern Era.

yes, archeological, because this is what we are talking about now.

Thank you

” We might think to create “temenos” (sacred areas), No fly zone space areas but it would be a failing Idea to do so”

Indeed the European regulations for space mission already identify two so-called “protected regions” in Low Earth Orbits (LEO up to 2000km) and around the Geostationary Orbit (GEO).

The regulations require that any new mission launched in those region can not stay in the protected region for more than 25 years, after than shall be moved to a reentry trajectory if in LEO or to a “graveyard orbit” if in GEO. Moreover, any mission shall be designed to avoid releasing debris. Other space agencies are adopting similar regulations. All the regulation are inspired to the United Nation Liability Convention. The problem are the thousand of debris left in the past, during the “space race”, and by the accidents that are occourring. A lot of that stuff is from military projects, mainly decommissioned communication military satellites from the Cold War age.

Anyway, the worst event was the Chinese anti-satellite test in 2007, that released the biggest cloud of debris ever created, and well inside the LEO protected region.

I tend to agree with you in term of finding a now roles in assessing this as a crimes!