On 10 February 2009 two satellites collided in orbit – a good time to think about some of the rules governing objects in outer space

Satellites don’t collide often, but when they do, the result is striking: they impact at enormous velocity (‘hypervelocity collision’) and can be pulverised into hundreds or even thousands of pieces of debris. Mind you, that debris doesn’t immediately fall to Earth. It continues to orbit around it: hundreds of uncontrollable satellite left-overs, ready for their next encounter. So who is liable when two satellites collide? Astonishingly, not necessarily the owners. It’s also not the operators who controlled the satellites (or stopped doing so). It’s what space law calls the “launching State”, i.e. the state which launched the satellite or procured its launch service, or from whose territory or facility the satellite was launched.

This international rule adopted in the early days of spaceflight (the 1950s and 1960s) seemingly allows for easy identification of a ‘culprit’: a spectacular rocket launch is difficult to hide, after all. But 21st Century spaceflight has become a little less simple: international joint ventures, private operators, cross-border cooperation, aerospace vehicles – that’s much food for thought for the lawyers and the regulators. Compare the dusty dirt roads and horse-drawn cabs of yesteryear with the traffic volume on a modern highway nowadays. Perhaps it is becoming time to discuss space traffic management too, just as we gradually introduced detailed rules for regulating terrestrial road traffic, from bikes to trucks, from pedestrian zones to freeways.

Space law is a really fascinating field covering the legal framework for activities conducted in outer space. But it does need to try and keep up with all the major developments we are witnessing in space and be on hand to step in when things do not go entirely according to plan.

Discussion: 6 comments

Let’s get something clear: all objects with the same mass and in the same orbit have the same orbital velocity (v).

If they meet head-on, then their relative (impact) velocity will be 2v – very big; but if they are chasing each other it will be zero (0) – so they will never collide.

However, the probability of either of those limiting cases is infinitesimally small and the severity of any collision will depend on the phase angle between the respective orbits – 180° for the former limit and 0° for the latter. So, they don’t ALWAYS collide with enormous velocity.

But, when traveling at 180 degrees, who has the right of way?

The fact that the ‘launching State” may be held internationally liable for the damage caused by its fault or the fault of whom it has to respond for, doesn’t prevent the operator (or eventually the owner) to be held liable, but on the ground of applicable national law.

That is correct. The blog entry focuses on international space law, keeps brief and presents the concept of the ‘launching State’ in the form of a pointed remark. Aside of the discussion of liability under international law, an owner or operator may be held liable on the ground of applicable domestic law

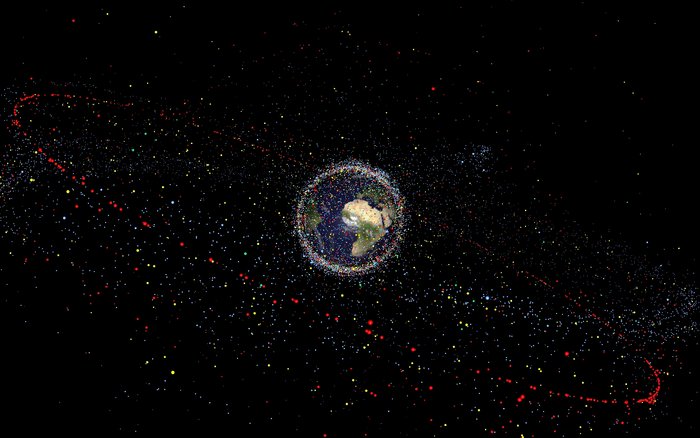

The problem is that it is not easy to identify the Launching State. There are roughly 3,500 space objects carried on national registries, yet we know there are at least 23,000 objects large than 10 cm in orbit:

https://swfound.org/media/171984/weeden_permission_to_engage_june2014.pdf

It is probably impossible to positively identify the Launching State(s) for all of those 23,000 objects, let alone the 500,000 or so objects smaller than 10 cm that are largely untracked.

You certainly have focused on an important point. There is an obvious need to do some global planning ahead for issues such as you discuss which will arise as more and more players become involved in space and as technology advances. I remember my friend, Carl Christol talking about thisl