With ESA’s Biomass in the latter stages of development, two intrepid scientists are braving the cold in the icy reaches of Antarctica for two months to take measurements from the air and from the ground to help prepare for this new satellite mission.

Here’s the next report from Jørgen Dall and Anders Kusk.

15 January 2024

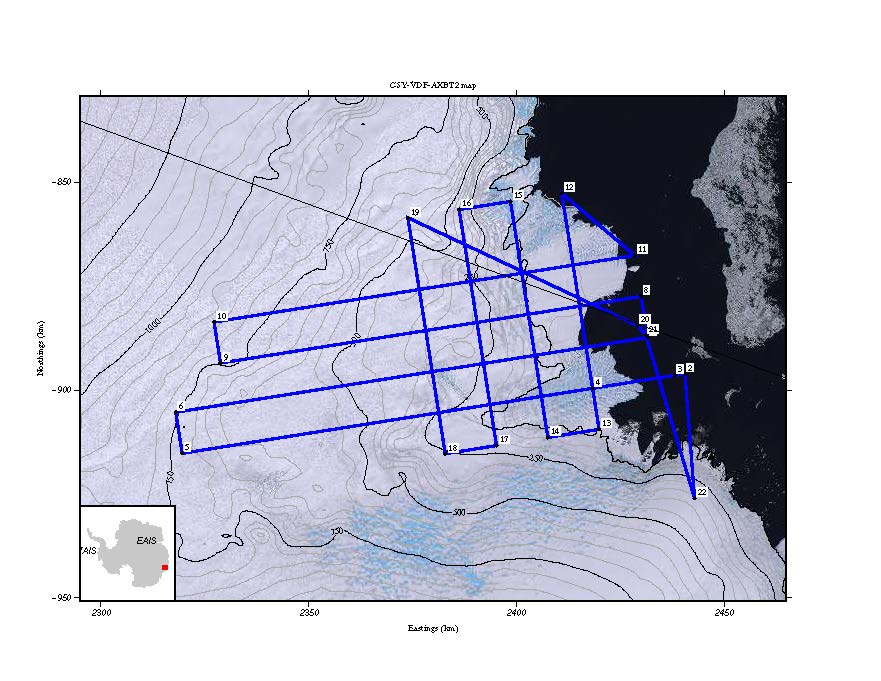

With the radar configured for ice sounding, we flew over Law Dome and the Vanderford glacier.

Vanderford tracks. (DTU)

18 January 2024

We headed off to the Concordia Station on the Dome C plateau, 1100 km from Casey. We would have left Casey the day before, but bad visibility at Casey forced us to change our plan.

We checked the orientation of the radar reflector when we passed it on our way to Casey Skiway.

Checking the radar reflector. (DTU)

This was to ensure an accurate calibration of the airborne radar data and a proper assessment of the feasibility of using the Antarctic ice sheet in the future to calibrate the Biomass mission’s synthetic aperture radar data.

Additional survival gear is required for such a long flight over the ice sheet. Dave, our flight engineer, joined us this time to take care of the aircraft upon landing in Concordia.

Survival gear and Dave aboard. (DTU)

Since the Basler aircraft does not have a pressurised cabin, we needed oxygen during the transit.

Oxygen supplies. (DTU)

It’s cosy aboard. (DTU)

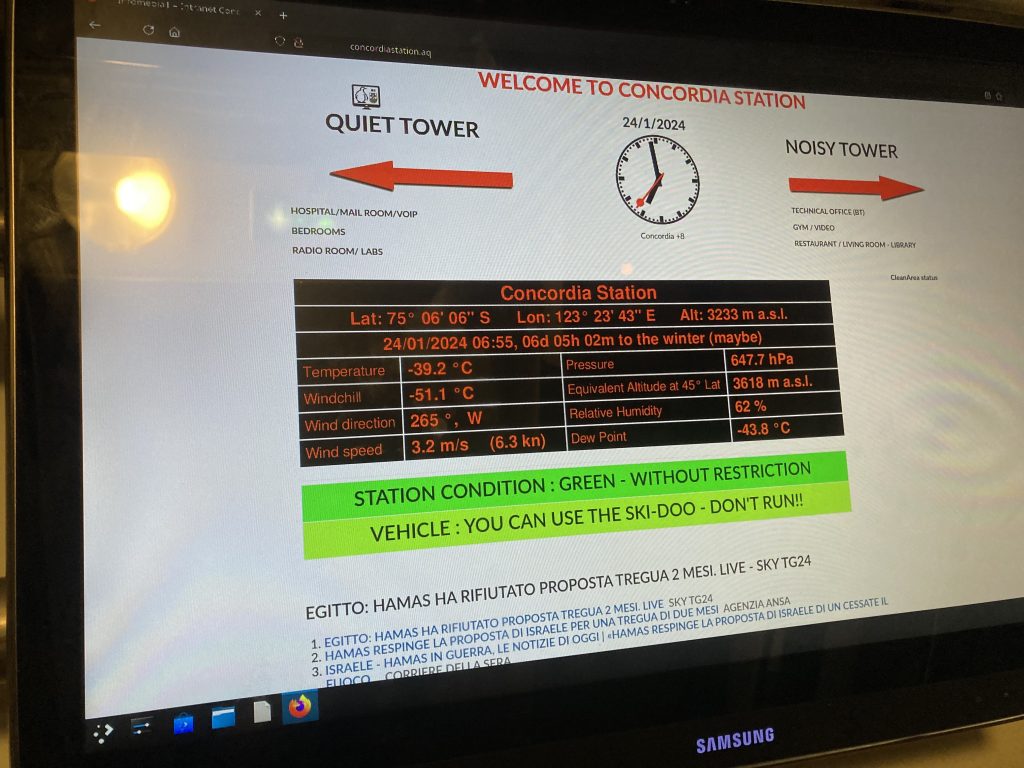

Concordia is at an elevation of 3233 m, and we want to fly an additional 2000 m over the ice sheet to maximise the coverage of the radar imagery.

After more than three hours with the Polaris radar configured for synthetic aperture radar mapping, we finally reached Concordia.

Concordia below. (DTU)

Basler parked. (DTU)

Concordia buildings. (DTU)

The station leader, Riccardo, gave us a warm welcome, but the air temperature was terribly cold. When we left Concordia a week later it was even colder.

Chilly. (DTU)

Coats for aircraft. (DTU)

Proper dressing is a must, and even the aircraft engines must be protected against the cold at night.

Riccardo took us on a guided tour around the station. It was interesting to see that ESA has a small lab in Concordia and we were surprised to see that Concordia has a ‘greenhouse’.

Concordia’s ‘greenhouse’. (DTU)

During the tour in the main buildings, we found it really exhausting going up the stairs. The effect of going from sea level to an equivalent altitude of more than 3500 m in just a few hours was very significant. Coming to Concordia, a two-day rest is required to avoid altitude sickness, such as headaches, nausea, dizziness, or worse.

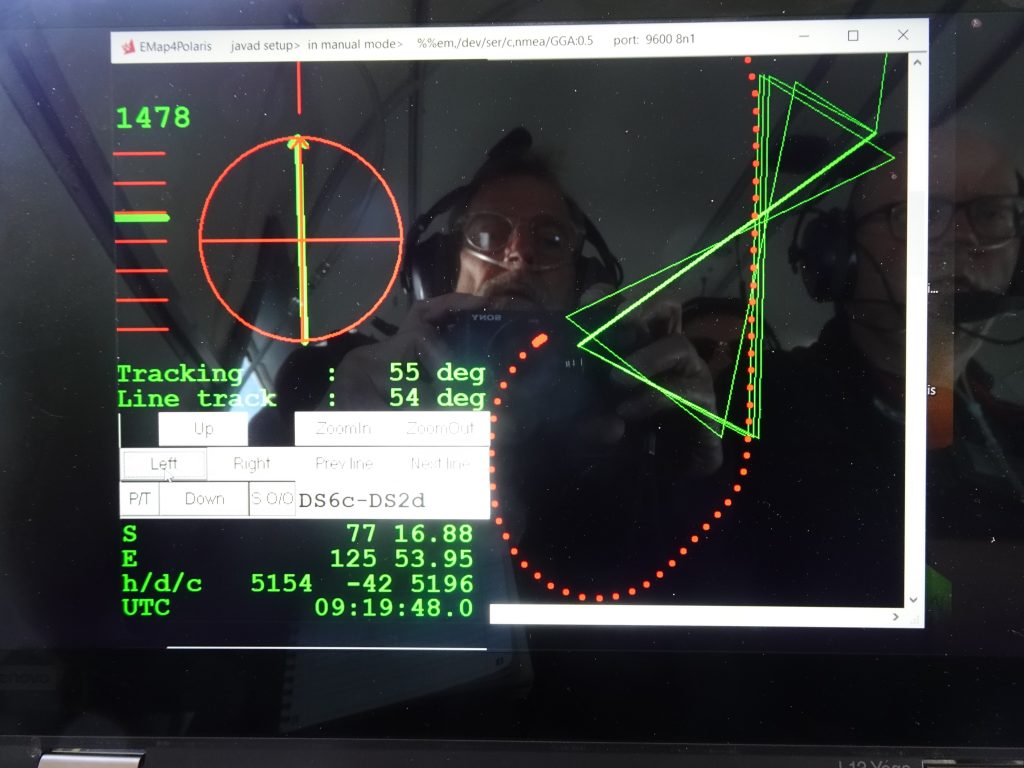

Not to waste time, we had a 2½-hour flight in the afternoon, which was acceptable as we had oxygen onboard. After refuelling and a bio break we collected synthetic aperture data data over a site 250 km south of Concordia. This is a potential calibration site for Biomass, where we aligned our flight tracks with the ascending and descending orbits of the satellite.

Flight tracks aligned. (DTU)

We measured the dependency of the radar brightness on the angle of incidence and the azimuth angle by shifting and rotating some of the flight tracks.

We also acquired Polarimetric Interferometric SAR (PolInSAR) data from very closely spaced flight tracks. On a small screen in the cockpit (visible in the middle of the photo above) the pilots could see the vertical and horizontal distances of the desired flight track from the aircraft (upper left corner of photo). It requires experience and concentration to keep the aircraft on the desired flight track with a small margin.

19 January 2024

While we stayed at Concordia we slept in a tent a few hundred meters from the main buildings. It is insulated and heated, and we were just four in a tent for eight, so it was quite comfortable.

Our tent. (DTU)

Tent comfort. (DTU)

The data we acquired during the transit to Concordia and in the following afternoon’s flight were impaired by radio frequency interference (RFI) and we were concerned if we could obtain good radiometric calibration of the airborne data after a potential RFI filtering.

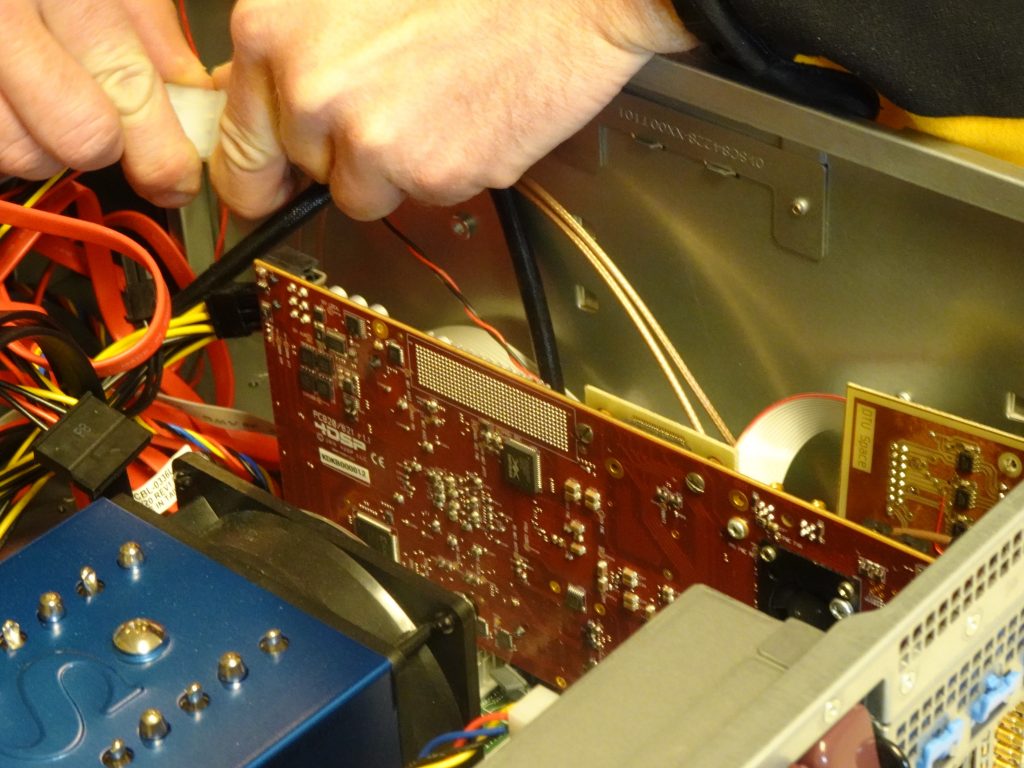

Apart from the RFI, the radar worked excellently. Several experiments and comprehensive data analysis suggested that the culprit was a commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) board, constituting the digital subsystem of the radar and hosting the inhouse-developed firmware.

We decided to replace the COTS board with a spare one, hoping that it would solve the problem.

Replacing the COTS board. (DTU)

The COTS board. (DTU)

21 January 2024

On Sunday, we had a flight over another potential calibration site for Biomass, a site 270 km west of Concordia where Aquarius scatterometer data suggest that the radar brightness is highest when acquired from ascending orbits. At the south site, it is highest when acquired from descending orbits. We were relieved to see that our data were no longer impaired by RFI, so we had made a good decision replacing the COTS board.

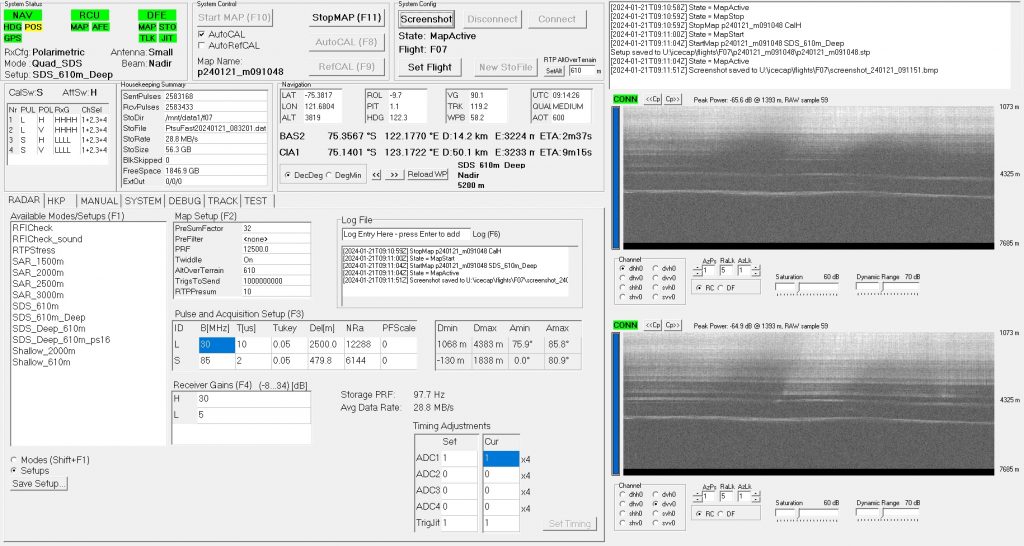

In the afternoon, we had a flight near the two ice-core drilling sites, Concordia and Little Dome C. With the radar configured for ice sounding, we profiled the ice sheet under the flight lines, from the surface to the base (the lower bright lines in screenshot below).

Ice sheet profiles. (DTU)

The Polaris radar can add to the existing radar data because it is fully polarimetric, capable of measuring ice anisotropy, e.g. crystal orientation fabrics (COF). The difference between the two images in screenshot is a result of anisotropy, which tells us about ice deformation in the past and is a valuable input to ice dynamics models, because the flow properties of ice are highly dependent on the COF.

23 January 2024

On Monday and Tuesday, the weather on the coast did not allow us to return to Casey. Instead, we had the opportunity to redo the flight over the Concordia South site, this time without any RFI. So, we achieved all that we had hoped to at Concordia, and we are very grateful for staying there for almost a week, enjoying the excellent food, generous hospitality, and intimate atmosphere.

24 January 2024

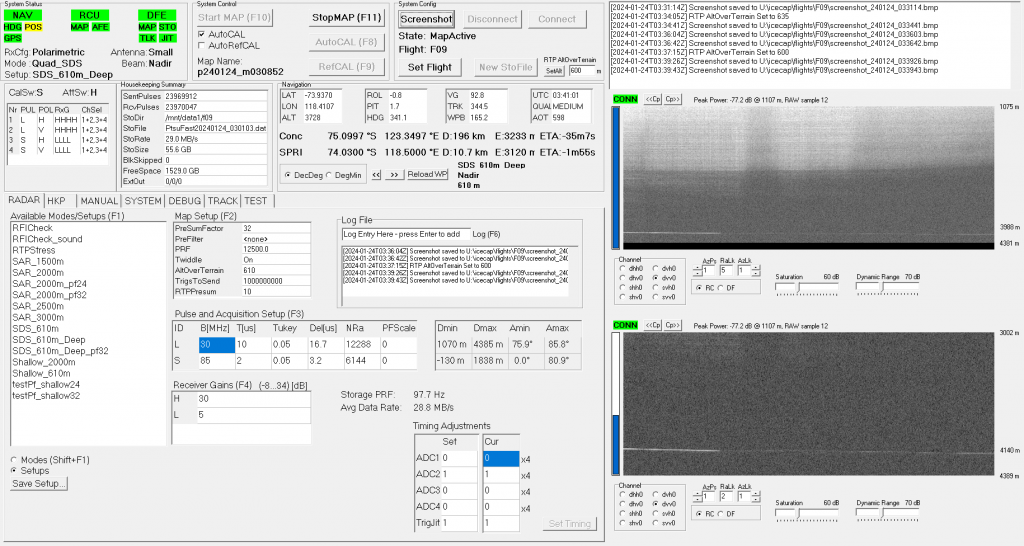

On the way back to Casey we primarily acquired sounder data, e.g. over SPRI Lake 33, where the ice is melting at the bed. The ice-water interface is particularly bright as seen at a depth of more than 4 km in the screenshot below. We are very satisfied that our radar can penetrate this deep. The radar frequency is not the best possible for ice sounding, but it is the lowest frequency that can be used from space, owing to the frequency allocation agreed in the International Telecommunication Union, ITU.

Bright ice-water interface. (DTU)

26 January 2024

Yesterday’s ICECAP flight focused on deployment of buoys in front of the Vanderford glacier, and today we were not flying at all because it is Australia day. Instead, we enjoyed a delicious barbecue and a cricket tournament (Internationals vs Australians) in beautiful surroundings. Not surprisingly, the Australians won.

Playing cricket in Antarctica. (DTU)

Post from: Jørgen Dall and Anders Kusk. (DTU)

Discussion: one comment

Respect goes to Jørgen and Anders, the aircraft crew and the DTU team for making the campaign happen! – and to the extreme cricket dude in a Hawaiian shirt and shorts playing at “silly mid on”.