We set sail on the evening of 20 May 2022 at 20:30 GMT, accompanied by the pilot to navigate us safely out of the Grafarvogur Fjord and into the wild, open northeast Atlantic.

As we left the Fjord, we encountered stubby black puffins flying close to the water in groups of five or six, wings beating furiously to speed up arrival at their evening roost. They were too far away to make out the ornately painted characteristic bill. From the distance, between them and the ship, we could only make out a flash of white on black, fading into the evening horizon. It was not long before we were head to wind and into the open ocean, where the rhythmic blue short waves in the protected fjord turned into writhing white horses. The ocean foamed and bubbled around us as the ship cut through the surf.

RRS Discovery accompanied out of Grafarvogur Fjord by the pilot boat. (credits: PML)

Having boarded RRS Discovery in November 2021, the research cruise cancelled, followed by a long but steady build up in momentum to 16 May 2022, to finally set sail, there was a sense of relief, excitement and wonder of going into unknown waters: the Arctic!!

With the Sun bowing towards the western horizon, the packing, travel and mobilisation both in Southampton and Reykjavik (see: From Plymouth to Southampton and on to Reykjavik), and this metal isle now rocking back and forth, it was time to bunk down and get forty winks, in readiness for dawn and the next part of this polar adventure.

The following day, the open seas and the perpetual motion of RRS Discovery had claimed many of the science party to sea sickness. Attendance at breakfast was scanty, to say the least.

For those that ate, after a hearty breakfast, it was time to turn on the underway water system, to fire up the instruments and to start measuring the marine phytoplankton in its coat of many different colours. Being so far north, at nearly 66°, was like reeling back the seasons that we had already experienced in the UK. The spring bloom at this latitude was in full swing, turning the ocean into a shimmering hue of green.

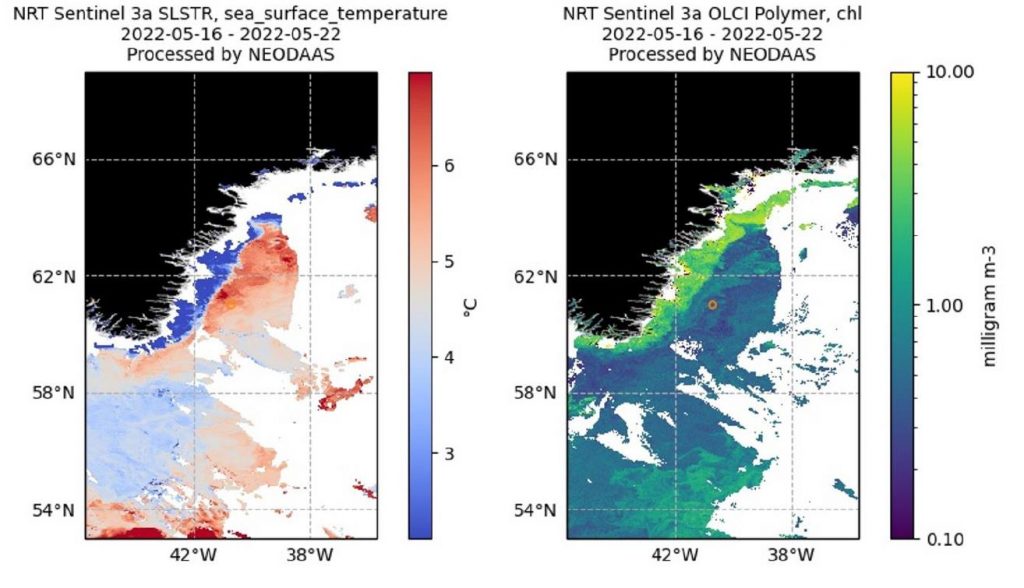

We were fortunate enough to have satellite support from the National Earth Observation Data Analysis Archive Service (NEODAAS) so that we could see the extent of the bloom. During DY151, we have received some spectacular satellite imagery from Copernicus Sentinel-3 and NASA VIIRS, which were processed by NEODAAS at Plymouth Marine Laboratory (PML).

The ocean green is grazed by both fish and birds alike, which are in turn consumed by larger predators, that builds an intricate web through which the phytoplankton flows to sustain all life in the ocean.

NEODAAS Satellite imagery: Sentinel-3A SLSTR Sea Surface Temperature and Sentinel-3A OLCI Ocean Colour Chlorophyll-a seven day composites from 16 to 22 May 2022. (credits: contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2022), processed by PML)

As the ship sailed west it was accompanied by the northern fulmar with its mottled silver- grey bull-necked stubby body with stout bill, like a short torpedo delicately weighted between aerodynamically sculpted grey wings. It flew close to the ship and occasionally paired off to skirt closer to the sea surface in readiness to plummet into the deep blue at any moment to capture unsuspecting fish. Its grey camouflage from above protects from marauding predators such as the skuas. The white underwing and underside are invisible looking upwards from the ocean, so that it cannot be seen easily against the dull North Atlantic and Arctic skies by pelagic fish.

We were also joined by bigger birds gliding effortlessly behind the ship, tail gaiting and looking for free cast offs from an expectant trawl. An alien species that I had never spied before: the Icelandic gull. At a distance it seems almost completely white except for the eyes, bill and legs, but close up the colour changes to a buff, pinkish white with a grey saddle over the back with occasional black streaks on the wing tips. It is out of luck; we are not trawling, not even water profiling and sampling, but simply taking in the pure Arctic air.

Northern fulmar and Icelandic gull. (credits: Sarah Barr, University of Leeds)

Cutting through the meandering streams of blue and green, flecked with white as the waves are picked up by the wind and then scattered back to the water as foam and droplets, to join to the sea again. Finally, we arrive at the receding winter ice on Greenland’s east coast.

The seawater temperature is ~0°C, the air temperature is -1.5°C but with the wind chill it feels like -6.0°C. A division between ruffled open water and an ice-water slick, like watery and lumpy porridge undulating with the swell. The first glimpse of the ice, a stark white line in the sea. The melting of Arctic winter morphing into a liquid summer as the frozen waters unite with the open North Atlantic, once again. With salt water constantly lapping against the aqua under belly of the white top encrusted ice chunks, like a sculptor meditatively chiselling at stone, to form her masterpiece.

At the ice-edge; a line in the sea. (credits: PML)

At the edge of the ice are the black guillemot. Noisy, squawking and sitting in groups, bobbing on the water. Black or greyish, white body with conspicuous black wing bars. Suddenly, the pomarine skua appears, adorned in the reapers sooty black cap and arrow like tail-tip. It shoots in circling menacingly around sitting ducks, causing waves of commotion as it weaves between them. The guillemot run clumsily along the waters surface. The skua’s ploy is working; create confusion amongst the flock and picking-off the weaklings in the ensuing turmoil that its presence creates.

Lumpy-porridge like ice, black guillemot, Icelandic gulls on an iceberg and more chunks of ice. (credits: PML; guillemot: Sarah Barr, University of Leeds)

The phytoplankton is so dense at the ice edge (see Plate 2. NEODAAS satellite imagery), that it clogs my filters, brownish-green, indicative of the first diatom bloom shed from the ice. A few days later, the sieves in the ships sink are clogged by swarms of zooplankton and the pumped underway seawater supply over-flows, creating Fantasia’s sorcerer’s apprentice in the lab.

Filters turning from white to green, thick with phytoplankton and zooplankton clog the sieve filters in the sink. (credits: PML)

The ice melt is a seasonal phenomenon, yet parts of the Arctic have been so transformed by rising temperatures in this region, that many scientists wonder for how much longer we can keep calling these waters ‘Arctic’. In time they will slowly merge into the North Atlantic and much of the ice will disappear and with it, many of those species that depend upon it.

Post from: Gavin Tilestone, Plymouth Marine Laboratory

Discussion: no comments