According to the Austrian Alpenverein, Austria’s national glaciers retreated on average 15 m over the course of 2019/2020. The retreat of mountain glaciers is well documented in the European Alps, and the recent IPCC Assessment Report 6 acknowledges once again the general decline of glaciers across our planet. On the global scale, it is satellites that have helped us better quantify this retreat. As a result, we now know that over the past twenty years global glacier mass loss has contributed approximately 21% to observed global mean sea level rise.

Glacier retreat is typically used as a symbol of climate change. The simplified concept is easy to grasp: a warming planet leads to a melting cryosphere. We are no longer surprised to hear the phrase “Our glaciers are disappearing”, and yet, when you hike into the mountains and come face to glacier-face, the first encounter can still take you aback.

Credits: ESA/A. M. Trofaier

In the summer, the glacier’s ablation area, the area where the seasonal melt runs off, is devoid of its pristine white. There is little snow cover – only ice speckled with grey and black hues. The glacier looks dirty. And while this is quite natural, if the glacier does not accumulate snow at higher altitudes its icy body will shrink. Those of us who have walked on glaciers have seen both their majesty and their despair. Those of us who monitor glaciers from space, know it too.

In August 2021, I travelled with Girls on Ice Austria – an all-female non-profit organisation that aims to inspire young women who are interested in science and the outdoors – to Tyrol in my native Austria, and climbed high into the mountains. ESA was pleased to support the expedition for this group of 15-17-year-old women, who were keen to challenge themselves and learn more about our changing planet.

Amongst the things we carried with us in our 15+ kg backpacks (mine was compassionately dubbed “Convoi Exceptionnel” due to its 17 kg): crampons and pick axes, an ice drill and ablation stakes, books on rock climbing, GPS devices, an infra-red camera, and smartphones prepped with software for albedo measurements.

Credits: L. Nicholson

Our trip starts in the Ötztal, first, at a camp site in Huben. Here six strong women, who we affectionately name our “gear fairies”, were prepped on where we were granted permission to set up basecamp for our expedition. The gear fairies carry all non-personal equipment for us. Then, with backpacks tightened around their hips, the girls start the long climb from the village of Gries at 1569 meters altitude. The glacier we set out to explore sits high up in the Stubaier Alps. Cupped by imposing horned heights that will outlast the cold white, the Bachfallenferner is a small glacier in substantial retreat.

We follow a typical alpine path through woods, climbing ever higher to where the trees become stunted and most of the green landscape gives way to grey gneiss and granite. The path turns, the rocks get bigger, and then the path turns again, and again, until there, looking skyward, you see an alpine hut – the Winnebachsee Hütte. We are now at 2362 meters. The views across a gorge towards a splendid waterfall are breathtaking.

Credits: L. Nicholson

We cherish our lunch break (Kaspressknödel and Kaiserschmarrn) but the climb is not over yet. The path now is rougher. First a short climb, then a drop, and another climb. The air invigorates.

On a nearby summit we meet day trippers, signing off their achievements in the summit register before turning back. One of them enquires about our group. “Ah, I thought you were carrying all that stuff because you were women.” Stunned and speechless. At 2512 meters above sea level stereotypes are perpetuated and a sudden anger rises. No, I did not bring my make-up kit. Yes, I am carrying a heavy bag. Respect me, don’t diminish and ridicule my strength. We remember why we are here, as role-models for the girls, and as he turns and walks away, we shrug off the unpleasant encounter and move on.

We need to get high before it gets dark. Down to a marshy plateau before the steep ascent. The footing is ever more difficult to keep as we scale the scree. The last hour before we make camp pushes me to my own limits but as we cross the glacier’s stream barefoot to reach the moraine on which the gear fairies stoically pitched our tents, the sense of achievement is real. We are at 2635 meters above sea level.

Markings on boulders show that the Alpenverein’s volunteers have been here; as was the glacier. We made camp next to marking A09 on the banks of a lake: the glaciers terminus was here in 2009. Since then, the glacier has retreated another 320 meters, and a lake has grown.

Credits: ESA/A. M. Trofaier

Later, after our first attempts walking on the glacier, drilling ablation stakes into the ice, and measuring the albedo of the ice, a storm was brewing, and we had to abandon camp and retreat back down to the Winnebachsee hut.We take time to do yoga before the rain arrives. In the sheltered barracks, sitting on mattresses laid out on the floor, we share experiences and talk about how women need to make space for themselves in a world dominated by men. One by one, all of us speak up.

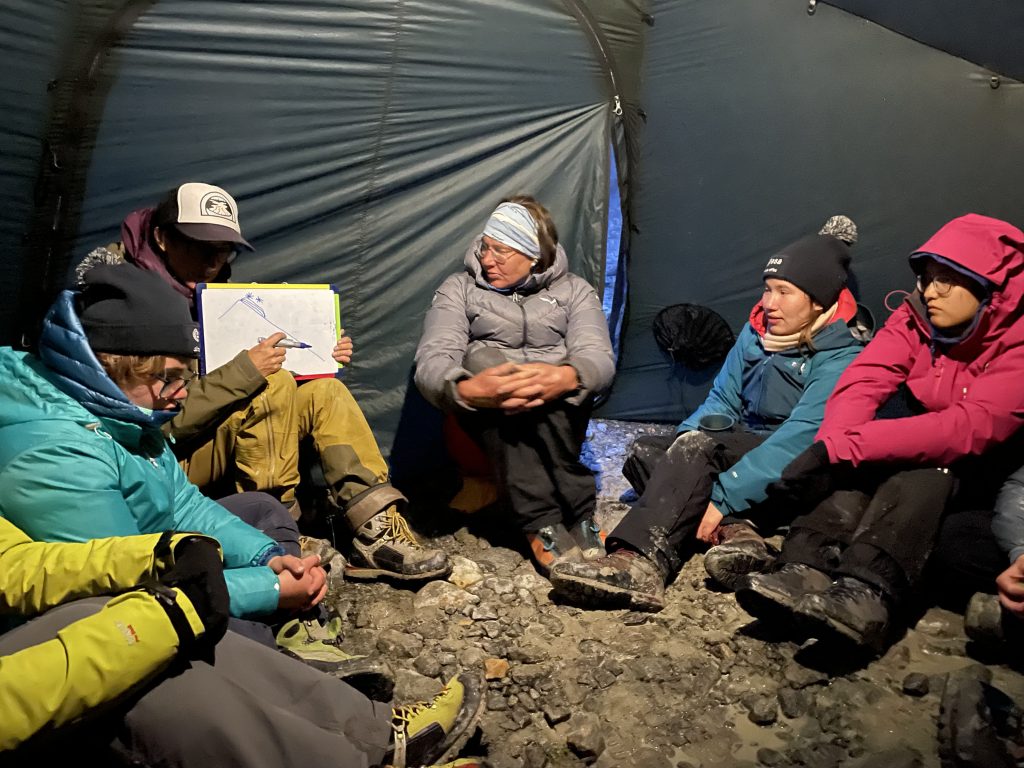

The next morning, I teach about the electromagnetic spectrum, satellite remote sensing and how we monitor glaciers from space. We talk about the different colours of a glacier, and what it means to measure its reflectance. At lunch we leave for basecamp again. The thunderstorm has passed in the night, but the rain stays for much of the week. In the mess tent pitched on desperately muddy ground, 14 women sit in a circle of makeshift benches of rocks and foam mats, planning experiments and talking about meteorology, climate and glaciers – physical geography 101.

Credits: ESA/A. M. Trofaier

Above the mountain tops, the clouds finally part, and give way to a sunny day. No time is lost, and our mountaineering kit is gathered. We climb the Bachfallenferner in three rope teams. Below our feet is snow and ice but look down and you might be staring into the abyss. Crevasses are mostly easy to spot. We break for lunch (nuts, crackers and cheese), and one at a time, each of us abseils into a 10-meter-deep crack.

Exhilarated by the experience we continue further until we reach 3000 meters. Here in the accumulation zone of the glacier, we do some snow density measurements.

Credits: ESA/A. M. Trofaier

A brief snowball fight follows, but there is not much snow to play with.

In the late afternoon sun, the snowpack is now wet, and we decide it is time to descend. Back in the ablation area we stumble over a moulin – a circular channel through which meltwaters drain. The intricate structures that form when the ice melts are powerful to behold.

Credits: L. Nicholson

That evening in basecamp, as we rest in the fading sun, the majesty of the day gives comfort but at night we remember that the Alpenverein’s volunteers will be back to mark yet another boulder in red with A21.

Post from: Anna Maria Trofaier, ESA Climate Office

Discussion: one comment

Interesting article! Wish all the girls good luck with any further research!