An International consortium of 25 scientists from 11 different countries joined the Royal Research Ship (RRS) Discovery in Southampton, UK, on 10 October 2019 to mobilise for the 29th Atlantic Meridional Transect and Phase 2 of AMT4OceanSatFlux.

Supported by ESA, the voyage builds on the work of the first phase of the AMT4OceanSatFlux campaign in 2018 to measure the flux of carbon dioxide between the atmosphere and the ocean.

RRS Discovery has a long research history. The first vessel, RRS Discovery (III), was built in 1962 and named after Robert Falcon Scott’s 1901 ship, The Discovery. At 90 metres, she was the largest general purpose oceanographic research vessel in the UK at the time. In February 2000, the RRS Discovery sampled in some of the largest waves ever recorded (~ 29.1 metres).

In 2013, the ship was replaced by RRS Discovery (IV), which was designed by A.S. Skipsteknisk. She is fitted with world class high-tech equipment for oceanic exploration as well as multibeam equipment for mapping the seabed, and a dynamic positioning capability to enable the operation of remote vehicles. Her cranes and over-side gantries, with associated winches and wires, will allow a wide range of equipment to be deployed from the ship to support state-of-the-art marine research.

RRS Discovery. (PML)

When joining the ship, installing all of the equipment necessary for the campaign can be frenetic. There was a continuous stream of material being winched aboard from early morning to late afternoon to provide all of the materials and supplies required for the scientific research and ships stores, to last the voyage across the Atlantic

Ocean, and beyond for the summer season in the Antarctic.

In amongst this, AMT4OceanSatFlux scientists installed an array of automated instruments on the meteorological platform, which included C-band radar that measure sea-surface dynamics, infrared radiometer that measure the surface temperature of the skin of the ocean, optical radiometers that measure the colour of the sea, high-frequency anemometers that measure wind speed and eddies and infrared instruments that measure the gas flux of the ocean.

Collectively this instrument package will build a picture of surface changes in temperature, wind speed, temperature carbon dioxide flux and phytoplankton blooms as the ship steams from the UK to its destination on 24 November 2019 in Punta Arenas, Chile.

The Meteorological platform on RRS Discovery with autonomous instruments to measure the sea temperature, colour, dynamics, wind speed and eddies and gas transfer over the ocean surface. (PML)

After setting up the autonomous instruments, we moved inside the ship to install the temporary laboratory spaces that would be our working environment for the next six weeks. The 250 boxes that we had packed into a shipping container in Plymouth were now carried to various parts of the ship and carefully unpacked to form our temporary labs. Unlike being on stable terra firma, where you can simply mount your equipment on a bench, setting up sensitive and expensive equipment on a ship requires a different approach. Everything has to be screwed, bolted, strapped, roped or bungeed to the bench to endure the roughest of seas, so that the equipment does not end up in bits on the deck.

The optical underway system carefully bolted and lashed to the bench. (PML)

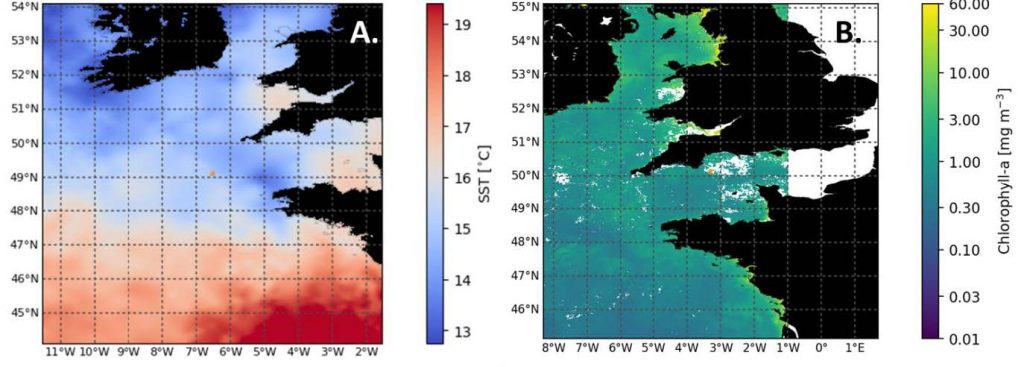

Having spent 48 hours mounting instruments and building our new lab spaces, we sailed out of Southampton at 07:00 on 13 October 2019 under grey and drizzly skies. On leaving the needles and coasting past the Chalky Giants of the Dorset Jurassic Coast, we were greeted by a green sea welling up on the bow. A late autumn phytoplankton bloom in the English Channel measuring over 1 mg m-3 of Chlorophyll-a (the active photosynthetic pigment in phytoplankton) with the water temperature of 15.5°C.

The Dorset Jurassic Coast. (PML)

To prepare for the long journey ahead, for not just the AMT4OceanSatFlux campaign, but also for campaigns beyond this into December in the Southern Pacific Ocean and Antarctic, an engineer had boarded the ship to check on the navigation and dynamic positioning systems. To do this we spent the first 24 hours tracking West and then East up and down the English Channel. Into day 2, and the systems were still being tested and the campaign was beginning to feel like the English Channel Transect rather than the Atlantic Meridional Transect. Finally we dropped the engineer off by boat transfer to Weymouth and we were underway. On the morning of 16 October 2019 we had our first sampling station at 08:00 in the green waters of the Celtic Sea, followed by the second at 13:00 where the Chlorophyll-a concentration was still high for this time of the year at 1.2 mg m-3 and the sea temperature was 15.9°C. That evening, we had our first sighting of Dolphins!!

AMT29 first sampling station in the Celtic Sea. Water depth 130 m; mixed layer depth 43 m. (PML)

As we steamed South West through the afternoon, the sea became rougher and rougher, with the wind gusting at 35 knots and a large rolling swell crashing along the length of the ship causing it to roll abruptly. That night it was difficult to sleep; doors were slamming, objects in the cupboards were rolling and tapping, the ship was creaking and occasional waves would slam into the side of the ship causing you to roll over suddenly in the bunk and jarring you awake. Even the wooden slats of the bed under the mattress were sliding from one end of the bunk to the next. The pre-dawn station was sampled 04:30. We had passed from the Celtic Sea shelf and were now over the deep waters of the North Atlantic which extended to 4.5 km below our feet. As the conductivity-temperature-depth device was lowered from the ships gantry, we could see evidence of the Mediterranean outflow water at around 1000 m. The surface Chlorophyll-a concentration had dropped to 0.75 mg m-3 and the sea-surface temperature was 16.25°C.

The sea conditions continued to be rough that day. That morning everyone looked a little jaded from an interrupted night’s sleep. Some were sea sick and the numbers at breakfast were scanty. The swell was large and the wind still strong and the mid-day station was cancelled due to the sea state. As the ship lurched from one side to another being tossed around in this mighty swell, a roller would occasional crash on to the after deck spraying the gantry and cranes with salt. Never under-estimate the power of the sea – it is one of the most powerful forces of nature.

AMT29 first sampling station in the Celtic Sea. Water depth 130 m; mixed layer depth 43 m. (PML)

Post from Gavin Tilstone, Plymouth Marine Laboratory

Discussion: no comments