Hold onto your hats folks, we are entering the South Subtropical Convergence Zone!

From the deep blue waters between 10 and 35° S, one crosses over the boundary between the South Atlantic Gyre and the Antarctic Circumpolar Current into green waters. It can be a bumpy ride sailing through the roaring forties and then into the ferocious fifties. We have experienced 40 knot winds and a sea state of force 8!

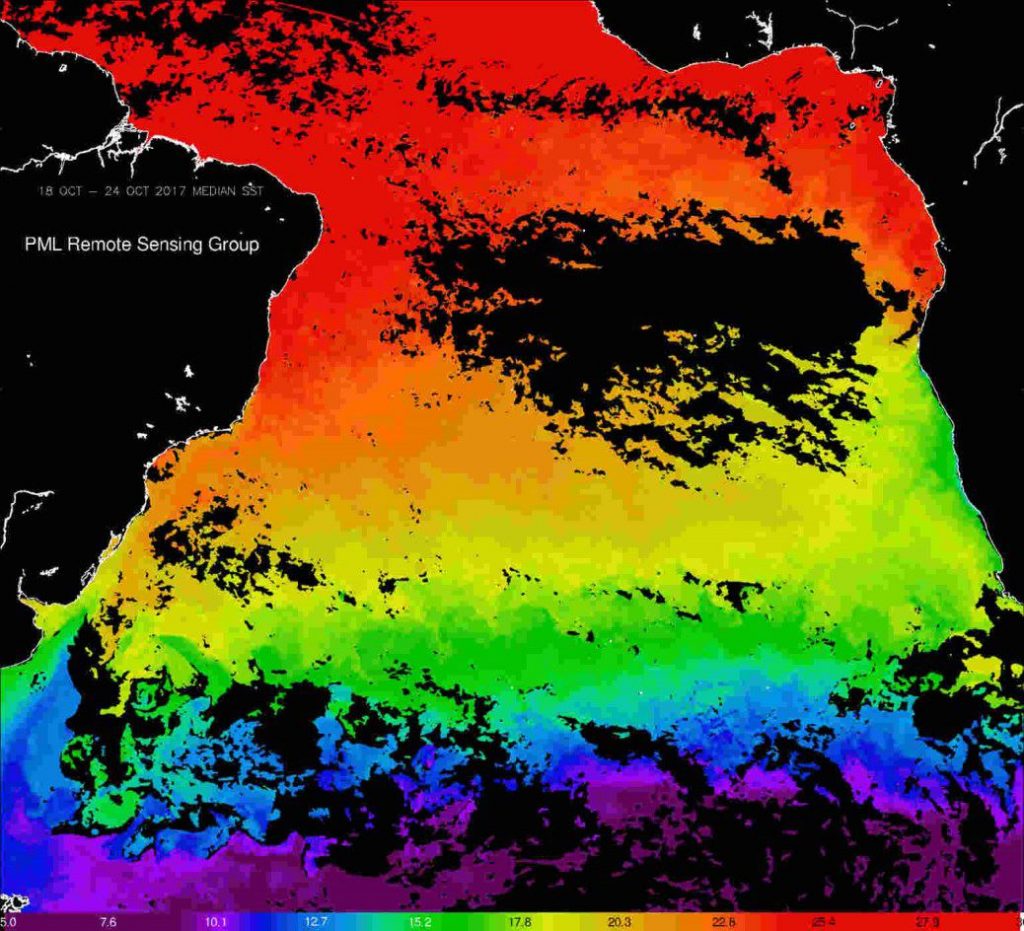

AVHRR sea-surface temperature median composite on 18–24 October 2017. The South Subtropical Convergence Zone is demarked from the Southern Gyre by the green band of 15C water. (Satellite imagery provided by SilviaPardo, National Earth Observation Data Archive and Analysis Service)

The voyage turns into a roller coaster ride, on which you better make sure that your scientific equipment is properly secured, otherwise it can end up in pieces on the deck.

The Subtropical Convergence is the frontal zone that separates the sub-Antarctic waters of the West Wind Drift from the subtropical waters to the north.

In this region there is a convergence, or ‘piling’ up of water, from the current in the surface mixed layer that becomes subducted into the oceanic thermocline. These dynamic processes combine to form strong temperature gradients. South of the front these water masses become highly mixed, bringing up nutrients from deep.

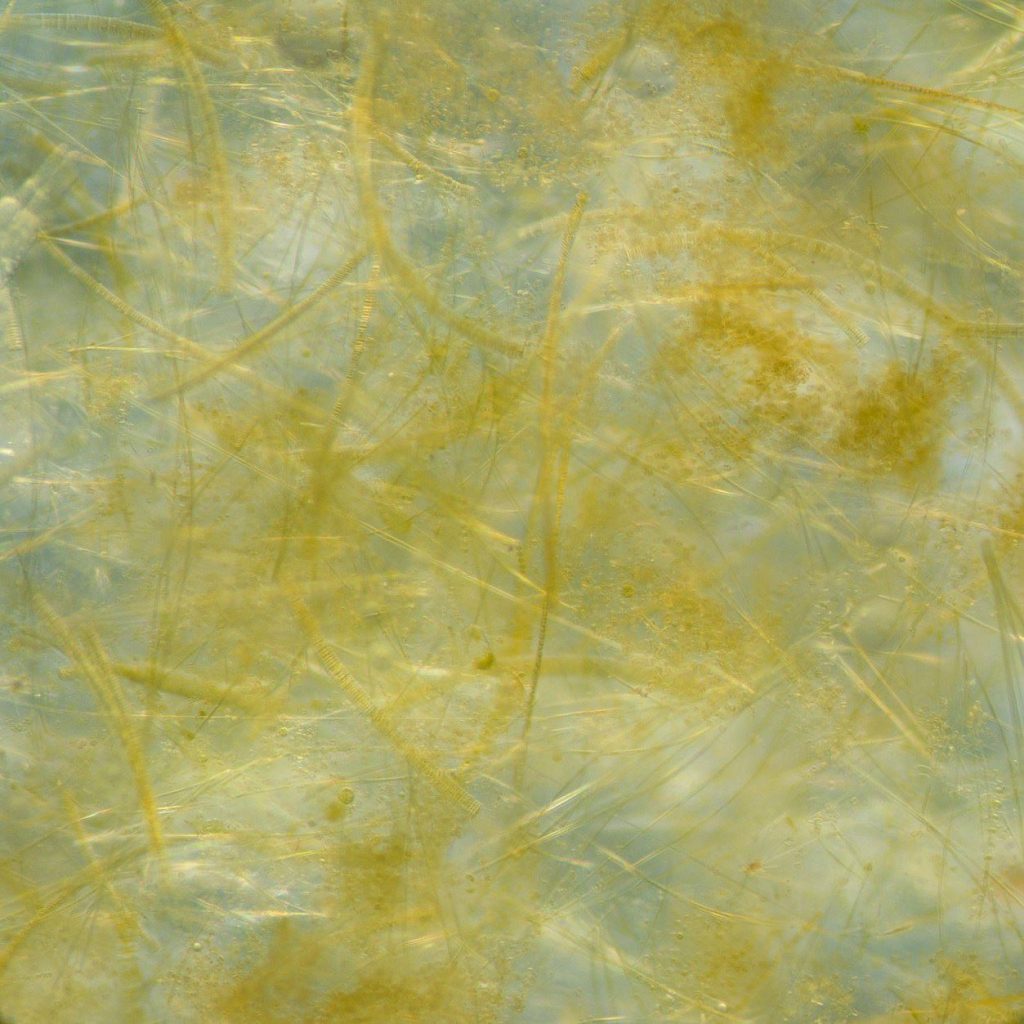

Phytoplankton bloom formed of a dense mat of diatoms in the Southern Ocean. (Erica Goetze, University of Hawaii, USA; Katjia Peijnenburg, Deborah Wall-Palmer & Lissette Mekkes, Naturalis Biodiversity Centre, Leiden, The Netherlands)

As nutrient-rich water is mixed upwards into the sunlit upper ocean, spectacular phytoplankton blooms form. From 35°S we crossed waters of 15°C and by 52°S the sea-surface temperature had plummeted to 1.5°C – a stark contrast to the tropical climes of the equator when we were on deck in t-shirt and shorts.

At 52°S, we crossed a phytoplankton bloom formed of mats so dense that it clogged the zooplankton vertical haul nets and turned our filters brown. Under the microscope, it became apparent that this was a rich diatom flora that included species such as Thalassiosira, Phaeodactylum, Chaetoceros and Rhizoselenia that collected in a mat of spaghetti comprised of long brown chains.

These blooms support a wealth of fish, whales, seals, penguins and other sea birds. To date, we have seen humpback whales (breaching over breakfast) & pods of pilot whales playing in the surf, minke whales, and wandering, sooty and grey headed albatross, and giant, cape and Antarctic petrels, prions, terns and lonesome Antarctic skuas.

Humpback whale & pod of pilot whales. (Ian Brown, PML)

It is breath taking to watch graceful albatross stroke the water surface with the tips of their huge wings as they patrol the wake of the waves for un-suspecting fish. Prancing prions skate on the surface as they pick out small fish and crustaceans from the very surface layer. This region is an important carbon sink, where phytoplankton draw down carbon from the atmosphere through photosynthesis.

As these massive phytoplankton blooms die and sink, the carbon sediments out of the surface layer and becomes sequestered to deep waters where it can reside for thousands of years. This natural sink is estimated to remove 3.5 million tonnes carbon from the ocean each year, which is equivalent to the removal of 12.8 million tonnes of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. It is a significant process in re-balancing the CO2 budget.

The South Atlantic Gyre and the Southern Subtropical Convergence zone are difficult to access and sparsely sampled. Projects such as the Copernicus AMT4SentinelFRM enable the collection of vital data for providing quality assurance of products from the Sentinel missions. After verifying the accuracy of these products, the data are used to monitor this blue planet that we depend on for food and for regulating our atmosphere.

RRS Discovery arrives at South Georgia on the 2 November as part of the AMT4SentinelFRM voyage. (PML)

South Georgia

At 54°S, we arrived at South Georgia, a sub-Antarctic island 167.4 km long and 37 km wide. The first impression is of snow-capped mountains, the peaks of which merge with the clouds. Between these craggy screes, fjords and bays have been carved out be iridescent glaciers. The surrounding shelf is less than 150 m deep, which makes the phytoplankton and krill even more abundant and therefore rich fishing grounds for a multitude of seals and penguins. South Georgia is an important breeding sanctuary for elephant seals and fur seals as well as king penguins. Nestled into the bay with a backdrop of tall icy crags is the British Antarctic Survey base, which is home to around 20 people who conduct research into this rich islands fauna.

The snow-capped mountains, fjords and bays of South Georgia. Top right: nestled in the bay, red roofs of the British Antarctic Survey base. Bottom right: RRS Discovery meteorlogical platform and AMT4SentinelFRM sensors. (Gavin Tilstone)

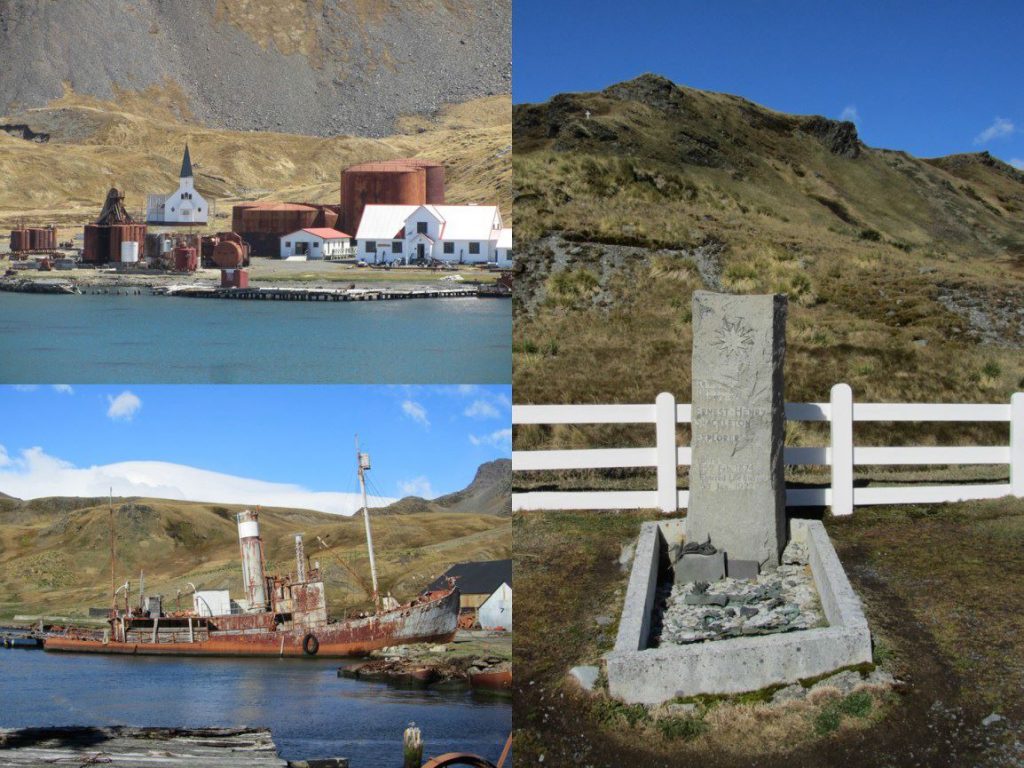

The main settlement on the Island is Grytviken, which is an old whaling station established by Norwegian sailor Carl Anton Larsen in 1904. The relics of ships, jetty, blubber vats and processing plants are now daubed in crimson red rust that is a historic reminder of the colour of the bay, which over 100 years ago, ran red with the blood of slaughtered whales.

Relics of the whaling station at Grytviken, and Sir Ernest Shackleton’s grave. (PML)

South Georgia has an epic history – in 1914 Sir Ernest Shackleton set sail for the island on Endurance from the UK. He reached the Wedell Sea in 1915 where upon pack ice closed in on the ship and wrecked it. Shackleton and five other men managed to flee the ship and reach the southern coast of South Georgia. From there they launched a rescue operation to save the remaining 28 sailors who had fled the ship to Elephant Island. In 1922, Shackleton planned to return to Grytviken, but prior to the voyage he suffered a heart attack and died. His grave and that of his right hand man during the voyage, Frank Wild, reside in the cemetery at Grytviken.

On leaving South Georgia, the scientists and crew aboard RRS Discovery embark on the final leg of our voyage to the Falkland Islands, crossing the wild Antarctic waters of the circumpolar current.

Atlantic Meridional Transect 27 scientists and crew of RRS Discovery. (PML)

Post from: Gavin Tilstone (Plymouth Marine Laboratory)

Discussion: one comment

So interesting and lyrical! Thanks for sharing.