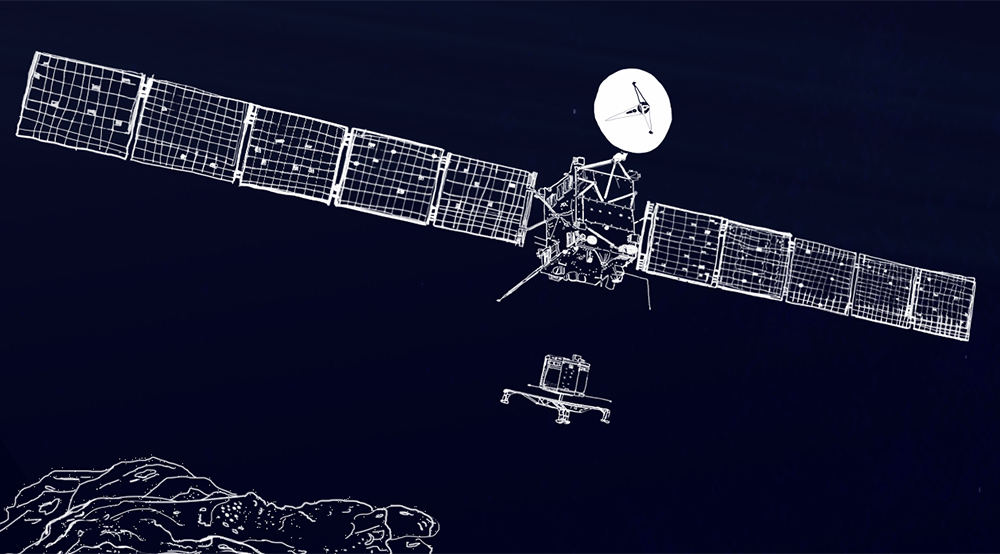

The latest update from the professional ground-based observing campaign of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, with inputs from astronomers Colin Snodgrass, Alan Fitzsimmons, Cyrielle Opitom and Emmanuel Jehin.

While Rosetta made a far excursion 1500 km from the comet to get a view of the wider coma and plasma environment during late September/early October, Earth-based observers have also been continuing to monitor the comet – from even greater distances!

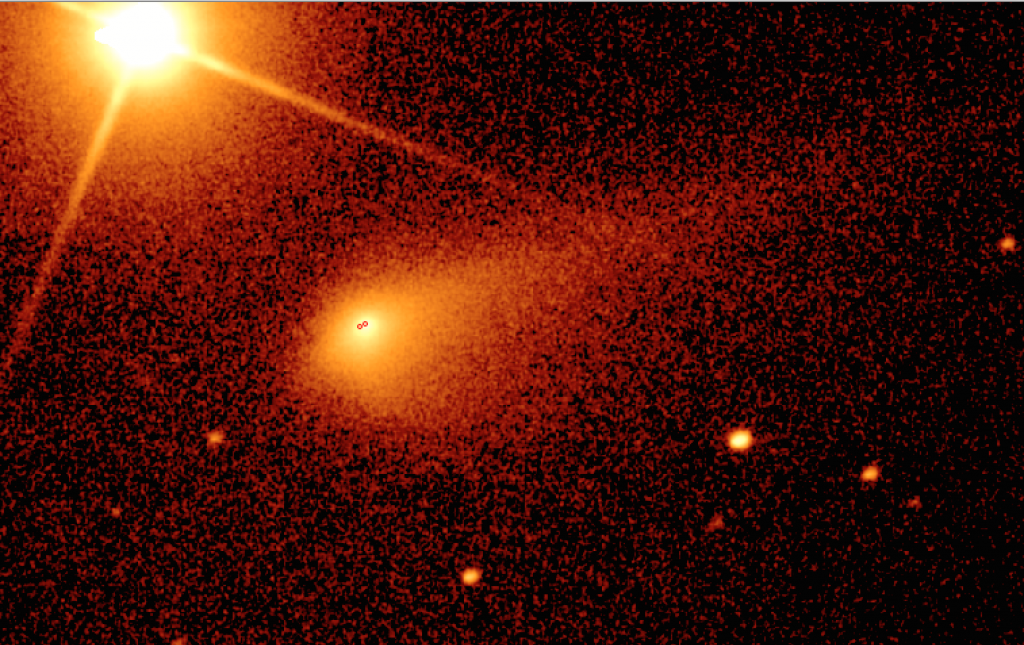

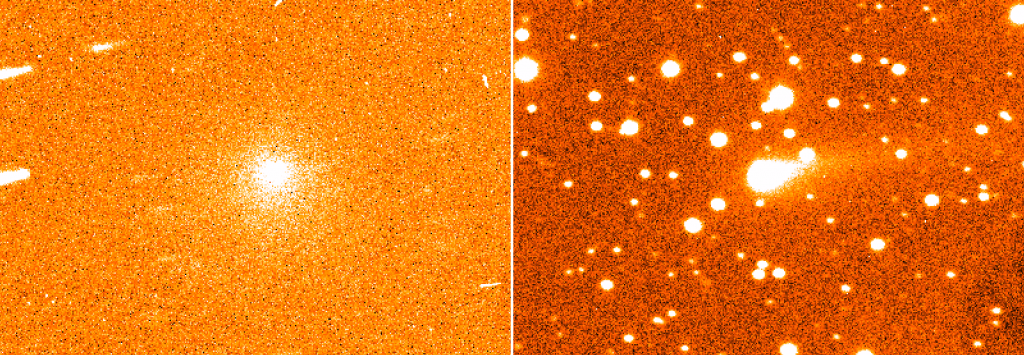

The image below was taken on 30 September, the same day that Rosetta reached its furthest distance from the comet during this excursion. To help put things into perspective, the image is also shown with two red dots: the right hand dot marks the centre of the nucleus, while the left hand one lies roughly 1500 km in the sunward direction, showing approximately where Rosetta was at the time the ground-based observations were made.

Caption: 20 second R-band exposure of Comet 67P/C-G using the Liverpool Telescope on 30 September 2015. The bottom image has been marked with two red dots to indicate the position of the nucleus and Rosetta, which was separated from the nucleus by 1500 km around this time. The comet was about 205 million km from the Sun on 30 September. The field of view is approximately 4.5 x 2.8 arcminutes, or 270,000 x 170,000 km. Credits: Alan Fitzsimmons / Liverpool Telescope

Peak brightness

Meanwhile, the ground-based astronomers have been analysing the comet’s brightness following perihelion – the comet’s closest approach to the Sun along its orbit – on 13 August. Based on measurements made by the 60-cm diameter TRAPPIST telescope located at the La Silla observatory in Chile, the comet appeared to show the peak in brightness at the end of August. Indeed, data obtained by the TRAPPIST telescope on 31 August indicated a dust production rate at the nucleus corresponding to approximately 1000 kg per second. The peak brightness on the same day was recorded as magnitude 12 (roughly 250 times dimmer than the faintest stars visible to the unaided naked eye, and thus decent-sized telescopes are needed to study the comet).

Since the peak dust production rate measured on 31 August, the overall activity has reportedly been declining steadily, following the trend anticipated from observations made of 67P/C-G during previous perihelion passages (see Snodgrass et al 2013).

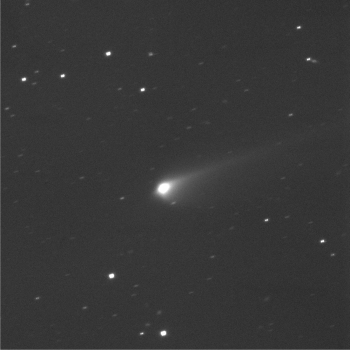

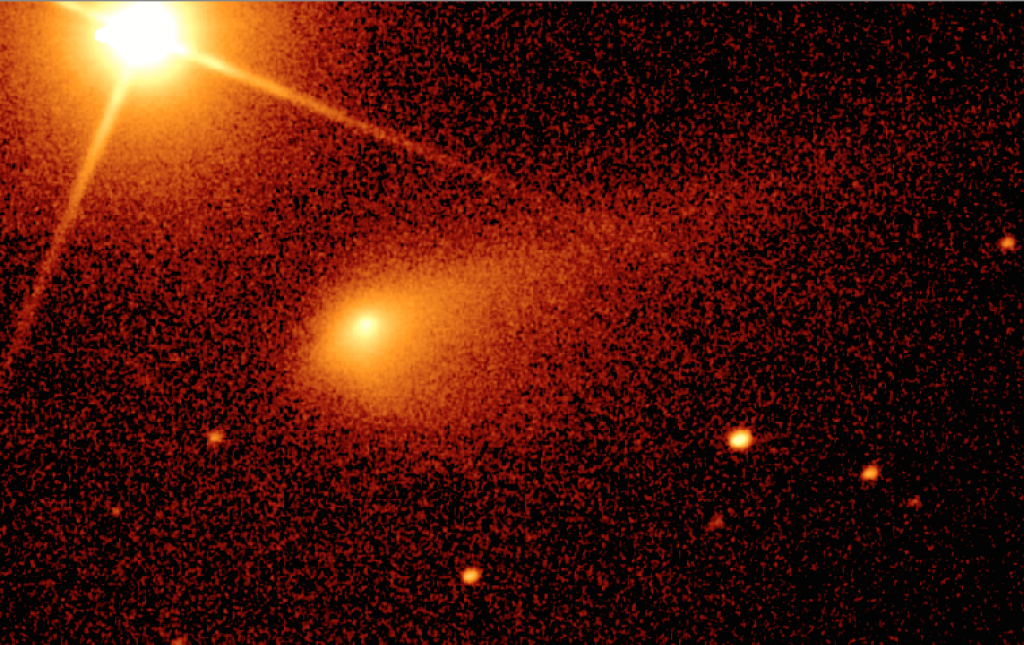

Comet 67P/C-G captured by the 2 m Liverpool Telescope at around 05:30 UT on 8 October 2015. The image is a combination of 9 x 15 second exposures, and shows the tail extending 400,000 km from the comet. On 8 October the comet was was roughly 270 million km from the Earth and 212 million km from the Sun. This image shows the full field of view of the IO:O camera on the Liverpool Telescope, 10.4 arcminutes on a side, or approximately 640,000 km at the distance of the comet. Credit: Colin Snodgrass / Liverpool Telescope

How much mass is the comet losing?

Using the 1000 kg/s dust loss rate, and knowing a few basic parameters of the comet’s characteristics, we can make some back-of-the-envelope estimates as to the amount of the comet’s surface that was being removed at this maximum. The calculation assumes that the density of the comet is around 500 kg/m^3, and considers the surface area of an idealised 4 km diameter sphere (5.0 x 10^7 square metres).

Based on Rosetta’s pre-perihelion measurements that indicate the dust:gas ratio was approximately 4 , that means roughly 80% of the material being lost is dust, with the rest dominated by water, CO, and CO2 ices. (Note: at the time of that blog post an estimate of 3 was made for perihelion, but the actual data has yet to be analysed.)

In any case, using 3 and 4 respectively, the total mass loss rate at its peak is likely in the range of about 100,000–115,000 tonnes per day.

Of course, that’s not a huge amount compared to the comet’s overall mass of around 10 billion tonnes. But nevertheless, a very simple calculation reveals that if, for example, the comet lost that much mass continuously for 100 days, it would correspond to roughly 0.4-0.5 metres of its surface being removed in that time.

Once Rosetta has returned to closer distances then more detail of how the comet’s surface has changed post-perihelion will be revealed.

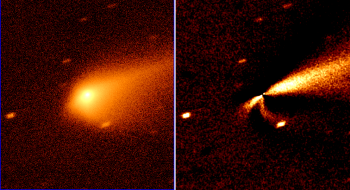

Comet 67P/C-G as seen by the Liverpool Telescope on 8 October. The Sun lies to the left of the comet, and the effects solar radiation pressure can clearly be seen driving the dust away, some of it to form the main tail to the right. Right-hand image: Processing to remove the symmetric part of the coma profile makes it possible to see the asymmetric structures in the denser region of the coma, including a southward excess of dust being bent back by the solar radiation pressure. Credit: Alan Fitzsimmons / Colin Snodgrass / Liverpool Telescope

Back to the comet’s coma, and from Rosetta’s close-up vantage point, several outburst events and hundreds of jets have been observed coming from the nucleus of 67P/C-G. It is not possible to discern these features directly from ground-based observatories, but processing of these images reveal clear asymmetries in the coma (see image above). Combining the big-picture views obtained by ground-based telescopes with Rosetta’s close-up study of individual jets and outbursts will help scientists understand the processes at work on the comet’s surface during these active periods, and how they are linked into evolution of the coma on the larger scales.

Coma gases

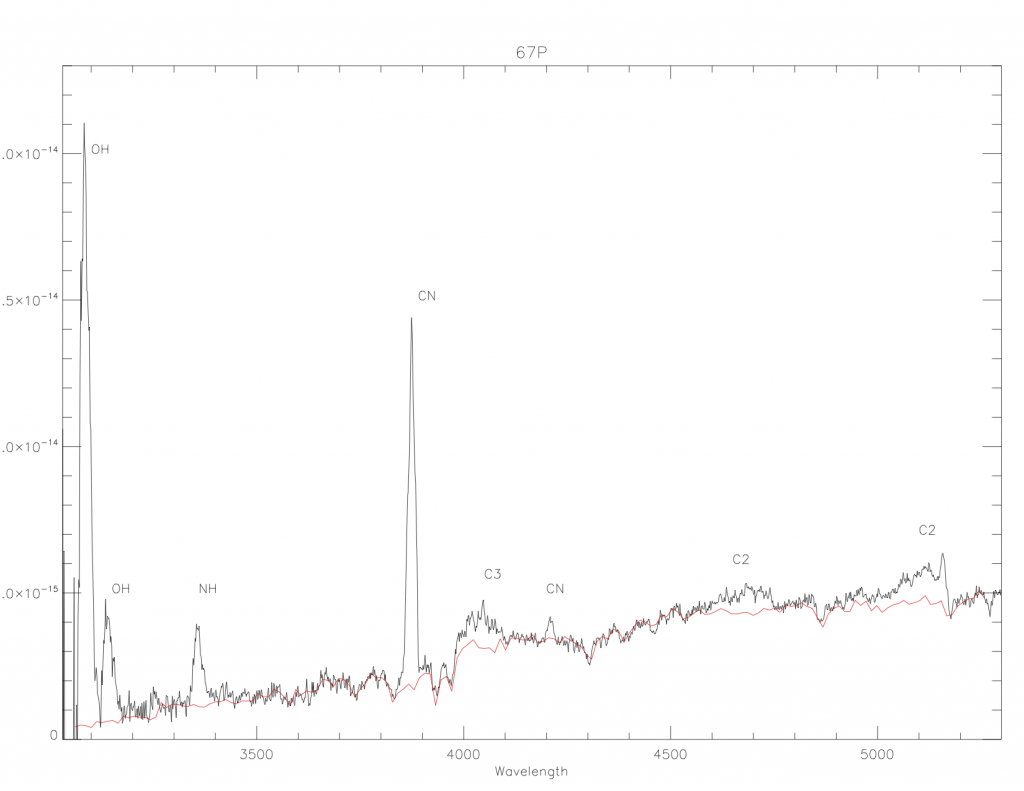

As well as the brightness and structures in the coma, astronomers are also busy analysing the chemical composition of the coma gases. These gases are illuminated by sunlight and glow at different wavelengths depending on their chemical make-up, allowing them to be identified and measured using a spectrograph, which splits light into its constituent wavelengths (as can be seen with a prism).

Now that the comet is relatively bright, many spectrograph-equipped telescopes are being used to measure the composition of the coma and the relative production rates of gases.

The LOTUS spectrograph was designed, built, and commissioned on the Liverpool Telescope in only six months, specifically for observations of Comet 67P/C-G. The previous spectrographs on the telescope were optimised for observations at red wavelengths, but the brightest gases in cometary comae emit most of their light at the blue-to-green end of the spectrum: this is why images of bright comets have a blue–green glow.

One of those gases regularly monitored by LOTUS is the cyano-radical CN, often referred to as cyanogen, the name for its molecular form (CN2). CN is a toxic gas and fluoresces at blue and near-UV wavelengths, as well as in the red. CN in the coma of a comet is thought to be produced when the toxic gas hydrogen cyanide (HCN) is dissociated (broken apart) by sunlight, and it is one of the most-widely studied gases in comets, giving some measure of the changing levels of activity.

Other gases commonly seen in the comae of comets include the CH, C3, and C2 radicals, the latter glowing at green wavelengths. Another important component is the OH radical, produced when solar ultraviolet photons split water molecules, of which comets have plenty.

OH glows in the near-UV and can be hard to study from Earth, because ozone in our atmosphere absorbs at these wavelengths. That’s a good thing for humans, as UV light is harmful, but makes it difficult to observe the OH emission from comets with ground-based telescopes.

Observations of OH from Comet 67P/C-G have been doubly challenging, as its apparent proximity to the Sun in the sky meant that it could only be studied in twilight, close to the horizon. The extra path length through more of the atmosphere led to even more absorption.

Fortunately, on the same mountain as the Liverpool Telescope, astronomers had access to the larger, 4.2-m diameter William Herschel Telescope (WHT). While the WHT has been surpassed in collecting area by the new generation of 8-m class telescopes, it has some unique strengths, not least its very sensitive spectrograph ISIS, optimised for observations and blue and near-UV wavelengths.

10 minute spectrum of Comet 67P/C-G using the William Herschel Telescope on 20 August 2015. The red line shows the part of the spectrum due to sunlight reflected by the dust grains in the coma. The spectrum has been corrected for the wavelength-dependent absorption caused by the atmosphere and for instrumental effects. Credits: Alan Fitzsimmons / WHT

This makes the WHT an ideal telescope for studying comets, and thus it was used to observe 67P/C-G in the early morning twilight of 20 August and again on 2 September. Even though the atmosphere transmitted only 3% of the UV light coming from OH molecules, there was enough water being released by the comet and therefore OH being produced that ISIS was able to make a clear detection of this gas.

These measurements allowed astronomers to calculate the amount of water being released by the comet in mid-August, yielding 90 kg per second. By comparison, Rosetta’s MIRO instrument measured up to 300 kg of water being released per second around perihelion.

Given the variability in the amount of gas being released from the comet at any given moment and uncertainties in the physical models applied to both the in situ and ground-based data, this is considered pretty close! As both sets of data are further analysed and the models refined, these numbers will likely move even closer.

CN emission (left) and dust emission (right) of Comet 67P/C-G on 22 August 2015 with the TRAPPIST telescope. The image is 4.3′ x 8.7′, or 340,000 x 700,000 km. Credit: Cyrielle Opitom / Emmanuel Jehin / TRAPPIST.

And finally, what about the CN gas? Through a quirk of quantum physics, it is much better at absorbing and re-emitting light from the Sun than OH. So even though the CN emission from 67P/C-G was almost as bright as the OH emission, it only required the release of a mere 0.13 kg of HCN per second from the nucleus.

These ground-based observations of the constituents of the coma of 67P/C-G continue to give vital complementary information to that being obtained from the unique vantage point of Rosetta.

Discussion: 21 comments

What is the big bright object at top left of the first and second images?

It is a bright star.

The lines are diffraction spikes caused by the spider support that holds the secondary mirror of the telescope in place.

Must be a star. I ran my not overly impressive desktop observatory for that date and location, but there is nothing showing with that separation from 67P. The closest star I could get was 5 arcminutes away, just after 67P rose.

Hi Solon

That’s a relatively bright background star that the comet was moving past as seen from Earth. The star is called HD81192, and with an astronomical brightness of magnitude 6.6 it is slightly too faint to see with the unaided eye, but it was still about a thousand times brighter than the comet.

Great ground-based observations. I’ll note that 67P is still maintaining it’s asymmetric overall coma shape. This distinctive coma has been present this time and was seen in prior apparitions. I would presume that it is due to the long-acting North Polar dust jets combined with the

orientation of the axis of rotation.

The fourth image (8 Oct) bears this out with special imaging of the inner coma of 67P. It shows a strong downwards pointing jet plus a

sunward “antitail”. That dark object in the righthand image is a special “occluding bar” placed at the focal plane of the telescope in front of the

CCD imaging chip. This is placed to block the bright glare from the bright innermost coma and allow details to be photographed. The

principle is like when you need to see something on the horizon near the setting Sun you will put your hand up to block the Sun’s glare.

Annotated image from the Blog post:

https://univ.smugmug.com/Rosetta-Philae-Mission/EarthBased-Observations/i-XfckhzM/0/O/LT8Oct_coma–liverpool–annot.png

The object in the first images is a bright star and the “spikes” are caused by diffraction from the mirror supports.

–Bill

Being orbital periods 6.55,6.59,6.61,6.59,6.59,6.59,6.45.

Then next visit will allow for a very direct line of command at perihelion 0.2-0.4 AU? 2-4 minutes?

Source: https://www.cometography.com/pcomets/067p.html

Shouldn’t let her go unvisited. Fast track, low cost missions, fast instruments and cameras 🙂

No need for speedsters. Just two or three small drones ‘posting’ along her path. Is just our immediate neighborhood 🙂

Like your idea Logan.

I posted the original suggestion that NASA’s ARM mission (Asteroid Redirect Mission to capture a 100 ton asteroid boulder and bring it to a lunar orbit), INSTEAD go get a chunk of 67P, (Cheops?… or a smaller boulder?)

While at it, go pick up Philae and either bring it back home to mine its computers, or just get it repositioned in great sunlight and back up on line? (Batteries would be long dead but I understand Phipae can work directly off solar panels in good sunlight)

This all might not be not too bizarre, the timing of next perhelion roughly coincides with the ARM mission in 6 plus years, that works, and the ability to catch fast moving 67 is doable with the mighty SLS much more quickly than Rosetta’s ten year journey.

I would really rather NASA build on what ESA has already achieved around 67P rather than startng from scratch with an unknown rock… Wouldn’t you guys?

Meant… “Might not be too bizarre…”

😉

Hi Ram. Maybe testing ‘fly-fishing’, instead of redirection technologies 🙂

Logan: Very nice ideas.

Hello, using the presented numbers in this blog the 4000 m diameter body that looses 1 meter of its diameter per orbit would not last very long in an astronomical timescale. So the comet is regaining a lot of its lost material or the presented figures are totally wrong.

Short period comets like this are not expected to ‘live very long’; the supply is continuously replenished by gravitational interactions of long period comets with the gas giants, especially Jupiter.

Do you have the last bunch, Emily? 🙂

Most of it open, or at least free.

https://www.aanda.org/articles/aa/abs/2015/11/contents/contents.html

Interesting observations and excellent pictures however once again clouded by the insistence on the ice sublimation hypothesis as fact and therefore reflection of solar radiation as the only source of illumination. Much is being overlooked.

@OJ

“Much is being overlooked.”

Such as?

If you take the trouble to read it, much of this is not about ‘reflection of solar radiation’. The solar radiation iis absorbed by HCN, H2O etc, which photodissociate leading to fragments like CN in electronically excited state, which then emit. Its fluorescence, not ‘reflection’.

The dust of course does ‘reflect’ (scatter) the solar spectrum.

I like the blog!

So, we believe in ‘breathing’, long period comets, Harvey. Or is it just surface phenomena [Dried core’s core remain dry?]?

Sorry Logan I don’t understand your comment.

As far as we know long period comets spend much of a heir time doing very little at low temperature.

I guess the first few perihelia after they become short period might be a little different as the surface remodels itself so to speak? But as far as I know we have no data on the detailed surface morphology of a long period comet; maybe New Horizons will give us some clues in its post Pluto encounter.

Looking forward to that!!!