During its most recent close flyby last Saturday, where Rosetta flew within 14 km of the surface of the comet, the spacecraft experienced significant difficulties in navigation. This resulted in its high gain antenna starting to drift away from pointing at the Earth, impacting communications, and was subsequently followed by a ‘safe mode’ event. The spacecraft has now been successfully recovered, but it will take a little longer to resume normal scientific operations. Here is the full report from the mission team:

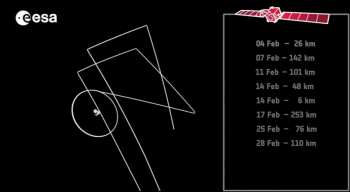

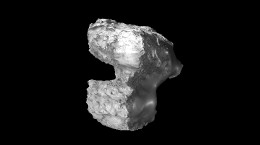

Rosetta has been flying a series of flyby trajectories around Comet 67P/C-G since February, allowing the spacecraft to collect scientific data from a range of distances. Its closest flyby to date took it just 6 km from the surface of the comet – over the Imhotep region on the comet’s large lobe – on 14 February. On Saturday 28 March, Rosetta performed a 16 km flyby (about 14 km from the surface), also over the comet’s large lobe.

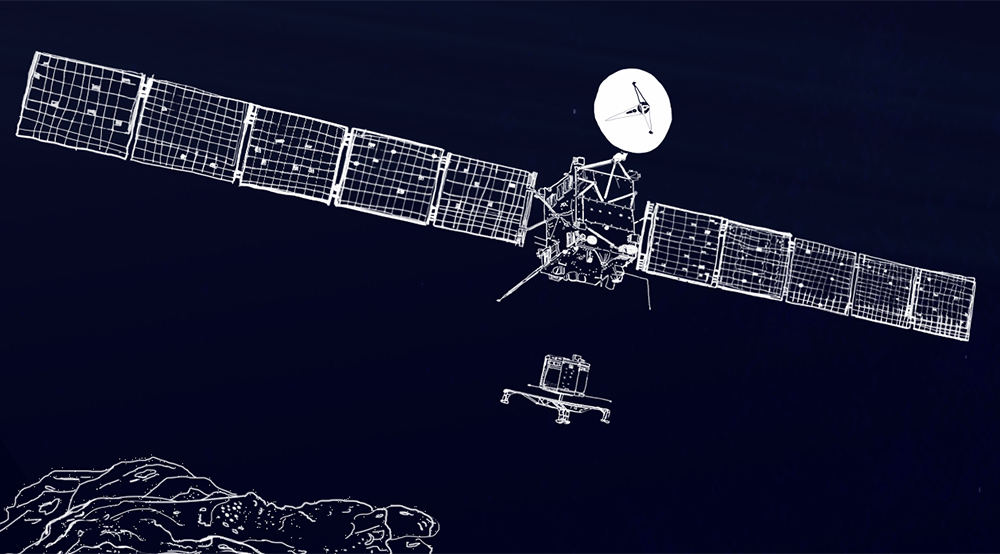

With activity from the comet increasing as it moves closer to the Sun, operating Rosetta close to the comet means flying through denser regions of outflowing gas and dust. This results in the spacecraft and its large solar arrays being exposed to significantly more drag. Furthermore, as experienced during the 14 February flyby, operating this close to the comet also has another effect: the spacecraft’s star trackers, used to navigate, are confused by mistaking comet debris for stars.

Crucially, the star trackers also help control the attitude of the spacecraft: by using an autonomous star pattern recognition function, they provide input to the the onboard Attitude and Orbit Control and Measurement Subsystem used to maintain the spacecraft’s orientation with respect to the stars. This allows the spacecraft to know its orientation with respect to the Sun and Earth. In turn, this ensures the spacecraft can correctly orient its high gain antenna, used to send and receive signals to and from ground stations on Earth. Correct attitude is maintained when the star trackers are properly tracking stars, and thus if this is interrupted, the spacecraft’s high gain antenna can drift away from Earth and communication with the spacecraft potentially lost. When the star trackers are not tracking, the attitude is propagated on gyro measurements. But the attitude can drift, especially if the spacecraft is slewing a lot.

Rosetta’s star trackers are marked in red, and part of the high gain antenna can be seen in the background. Credit: ESA/ATG medialab. (Note that this is a still image taken from our 2013 animation “How Rosetta wakes up from deep space hibernation”)

During the most recent flyby, a number of issues were reported, starting with the primary star tracker encountering difficulties in locking on to stars on the way in towards closest approach. Attempts were made to regain tracking capabilities, but there was too much background noise due to activity close to the comet nucleus: hundreds of ‘false stars’ were registered and it took almost 24 hours before tracking was properly re-established.

In the meantime, a spacecraft attitude error had built up, resulting in the high gain antenna off-pointing from the Earth. Indeed, a significant drop in the radio signal received by ground stations on Earth was registered. Following recovery of the star tracker system, the off-pointing was immediately automatically corrected and the operations team subsequently saw a return to a full strength signal from the spacecraft.

However, issues with false stars were still occurring. Cross comparisons with other navigation mechanisms showed inconsistencies with the star trackers and some on board reconfigurations occurred. While attempting to reconfigure those, the same error occurred again leading this time to an automatic safe mode on Sunday afternoon. Safe modes occur when certain spacecraft parameters fall out of their normal operating ranges and the spacecraft automatically takes measures to preserve its safety. This also includes switching off the science instruments to protect them.

From Sunday to Monday, the operations team worked successfully to recover the spacecraft from safe mode to normal status.

Rosetta is currently on a trajectory over 200 km from the comet, but a manoeuvre has already been planned to bring back the spacecraft closer to the comet next week. It is expected that limited science operations will be resumed in the coming days and weeks.

The science and operations teams are currently discussing the impact of the recent navigation difficulties on the current planned trajectories, possibly resulting in further replanning in order to ensure that the spacecraft can operate safely as the comet activity continues to increase towards perihelion in August.

We will share further status updates when the information is available.

Update 2 April:

A manoeuvre was successfully executed yesterday (1 April) to bring the spacecraft from a distance of around 400 km to 140 km by next Wednesday. More details will be provided next week regarding subsequent trajectories.

Discussion: 62 comments

Particle-o-sphere going real big.

Long exposure NAVCAM shots. Stars will show a well patterned trajectory. Projectiles don’t. Erasing the later. Un-smearing. The un-smearing algorithm is also the stabilizing algorithm. Once stabilized, reapply positioning. Easy said, easy talk. Lots of risks to be evaluated. Best wishes to programmers.

Should say: “… Once stabilized, take another shot. Repeat if necessary, then reapply positioning”.

Speculating magnetic terminator line [and beyond that, towards magneto tail] could be a little safer.

At 200km you could make comparative statistics of impacting both at solar and magnetic terminator lines.

Twelve hours samplings. Approaching cautiously, keeping the seismic sampling.

Logan: I assume from what you said that an all-sky star map is not built into the Rosetta software. A couple of naive questions: how much time does taking spectra take, compared to Navcam long exposures? Do particles have a distinctive spectral component which can separate them from stars?

Just being bold, Lodaya 🙂

[We are outsiders].

Imagining star trackers being very closed systems, software side included. Nothing to do there, except being far -and not so productive-. [Really hopping I am wrong about this speculation].

Just suggesting use of NAVCAM output to maintain attitude drift at bay, if gyro accumulating error due to impacting and lacking resets from ‘lengthy confused’ star trackers.

A star map has to be inside the star tracker’s system, I presume. A modern star tracker [and this is not the case] should have task specific, noise insulated pixel sensors, and physical filters above the lenses. Star ‘friendly’, from hardware up 🙂

As for ‘spectral’ differentiation, NAVCAM doesn’t, and no idea about time spent on OSIRIS multiple filter changes and shootings. Other array instruments lack the resolution.

Really would like to read a comment from more informed contributors.

“…by using an autonomous star pattern recognition function”. Emily said it 🙂

Autonomous suggest being a processing thread outside of Rosetta processors.

There have been telescopes built (or adaptors for existing telescopes) which will turn the whole telescope into a spectroscope for it’s entire aperture.

Look at the section headed “Objective Prism Spectrograph” on https://www.astro.virginia.edu/class/majewski/astr313/lectures/spectroscopy/spectrographs.html for some theory on them.

Whether the longer exposures would be worth the effort compared to taking more images and using software to discard the fast-moving points is an issue for calculation.

Thanks a lot for the illuminating lecture, find it easy to digest, Aidan 🙂 Think Lodaya refers to something like this:

https://www.astro.virginia.edu/class/majewski/astr313/lectures/spectroscopy/HyadesObjectivePrism.jpg

as star-tracking input.

[Center left band is not a star, or at least not a common star].

Interesting conversion:

…16 km flyby (about 14 km…

It’s not a conversion. The orbital distance is from the center of the comet while the surface is about 2km out from the center.

Presumably the distance to the center of the comet was 16km, while the distance to the surface was 14km. So two different measurements.

Allowing for 2 km of comet between surface and gravitational centre (barycentre), of course.

Well, next Rosseta will have to have a ‘falling falcon’ mode 🙂

Better yet, next Rosetta will send little ‘falling falcons’ to do the proxy sensing.

That’s really too bad, seems like something that might prevent further flybys. Having problems with the star trackers during the closest approach is reasonable, but seeing false stars even quite a bit after the flyby is a bit worrisome.

Daniel: This was anticipated, that is why the navigation team moved out from the 30 km orbit. The difficult thing is where to draw the safe boundary — 50 km away? 100 km away? And if you fix on some distance this week, what to do the next?

Right, they moved further away due to the increase in activity, I’m not sure as to how that pertains to my comment though? I’m a bit doubtful about them anticipating having tracking problems still a day after the flyby.

The February 14 flyby was over Imhotep but it did not go very close to the rest of the comet, quickly moving away in what Logan calls the “falling falcon” mode. The March 28 flyby was over the whole sunlit area of the bigger lobe including the jets over Hapi, so definitely would have been known to be potentially more dangerous. Another “falcon” swoop over the smaller lobe, hopefully also incorporating a search for Philae, but staying clear of the neck jets, seems risky but possible, and should give information on the relative activity of the head and the body lobes.

I agree, perhaps “un-smearing” above is an algorithmic way out.

We don’t have a good theory of how the dust around a comet moves/orbits around it (so it may be time to speculate one). The only reliable data for navigation close to the comet seems to be the Sun, suppose we fix its centre as one point. Perhaps one can fix a point on the comet (one that can always be seen from anywhere on the flyby). Can one use the Hapi jets, which seem to be a constant feature, as a third point? Asking the Sun to produce some other nice big jets which last a while might be good for navigation. I suspect that these crazy ideas of craning the camera this way and that to fixed regions may be quite impracticable. But what I am saying is that in the absence of help from the stars, it is the comet which may have to be used as the guide.

As Kasuha says below, the dust seems to be brighter, and we have seen images of big chunks moving away from the surface. Can even see some largish chunks 20-30 km away in the April 2 image (Gerald’s nonlinear magnification is helpful). Are these things orbiting the comet nucleus, or are they being pushed out in an antisolar direction?

Is it worthwhile dynamically fixing (I mean with one hour’s time, or more, between image and decision) one large chunk, then tracking its neighbourhood with camera while maintaining a quiet orbit at a reasonable distance, to see what happens to the chunk over a few hours? It might be interesting if it disintegrates. I think this is also untenable: if fixing the stars is difficult, fixing on a chunk should be harder.

As Logan says, we can say bold things without having to worry about all the ramifications.

Kamal

I’d presume that some dust has settled on the star tracker’s lenses and appears as false stars now.

i doubt it Johan. You would expect the star tracker to be programmed to be sensitive to apparent brightness, particularly if it was to recognise particular stars. Dust on the lens would be silhouetted. Perhaps the false stars are emitting photons.

It appears from these two close flybys that the dust cloud surrounding the comet is reasonably extensive. Is there a quantitative measure of this? Also, is there a measurement for the drag on the spacecraft?

There seem to be several risks now: the risk that we lose Rosetta (or communication to it, which is the same from our point of view) quite some time before perihelion, the risk that Philae won’t wake up, the risk that Philae wakes up but its situation is too precarious, and the risk that Philae wakes up but its communication to Rosetta is compromised in some way. It is a difficult job managing all of them. Best wishes!

Basically, density of particules and gas is divided by 4 when distance is multiplied by 2. So, even at hundreds of kilometers from it, there are particules. But then, of course, it depends on the direction of Rosetta around the comet, as particules and gas are sent in various directions from various parts of the comet, and then are deviated by several factors (light from the sun, heliosphere, magnetic field, gas pressure …). All together, probably extremely hard to estimate where it is safe or not, and subject to many uncertainties and unpredictable parameters … The only solid element is : it’s safer far from the comet …

Here’s an idea. Don’t fly so close.

We get more overall science for the long term if we play it safe for the moment.. Well right through perihelion, really. Get really close again when it is all died down, and get some real close “after” science and images for our before and after comparison.

I was thinking exactly the same thing…

But I doubt if the ROSETTA teams really need any advice on the matter. They’re presumably going to be spending a considerable time working exactly went wrong, for a start. I fear that close flybys may be a thing of the past. But looking on the bright side, ROSETTA has already sent back huge amounts of data from previous flybys on the essential properties of 67P which still await publication and analysis.

And as activity increases, we can perhaps actually better observe the nature of the jets (location, degree of curvature, fine structure, velocity, etc.) from a safe distance…

I guess there are also risks that in spite of the baffles on the StarTrackers, there might be particules on the lens…

Any soul found something about this issue? Seems star trackers have just ‘naked’ eyes.

I wouldn’t expect there to be a lens. Apart from keeping the CCD clean during the assembly/ launch phases, why would there be a lens?

Besides, CCDs all get hit by cosmic rays, sometimes resulting in “hot” pixels which are jammed on (or dark ones which are jammed off). So the image processing software will have the ability to handle this and to update the list of hot pixels. There’s certainly that element in the Hubble pipeline (I read it. Once. Too often.) and there are steps like that in regular astronomical image processing (taking “dark” frames and “flat” frames).

There is a lens, focussed on infinity. See

https://www.jena-optronik.de/en/aocs/astro10.html?file=tl_files/pdf/Data%20Sheet%20ASTRO%2010.pdf

For example.

It couldn’t work without a lens.

Thanks all the team for manage this issues. Go Rosetta!

Still, it’s good data. A known asoect/area and measurable yaw from flying through the dust jet will give a good handle on the”viscosity” (kinematics?) of the dust/gas jet.

Risks of exploration.

–Bill

I guess the reason is not just that there’s more dust in space but its brightness increased as the comet is getting closer to the sun, too.

And that’s assuming there’s no dirt on the tracker’s cameras, getting some there might be additional challenge.

I guess the safest way to get rid of (most of) false stars would be to create several (5-7) short exposure shots, then calculate median value for each pixel. Assuming the ship did not rotate in between them and there’s no dirt on the camera, that should get rid of almost anything that moves.

As Kasuha points: There are several reasons for gyros/star-trackers to be a single unit. [At least in software].

ROSETTA’s structural oscillations after multiple impacts, differing in magnitude, direction and hardness, plus the continuously changing situation on liquid propellant kinetics and slow dissipation of that energy.

Even if small, ROSETTA should be in a continuous state of ‘tremor’ during those close flybys.

Not difficult to imagine attitude vector accumulating error. It’s just the magnitude of the task.

The start tracker is focussed on infinity. Dust on the lens is completely out of focus; it doesnt directly produce a ‘false start’. If unilluminated, its main effect is simply to reduce the intensity, just as the F stop does on a camera. If on the other hand strongly illuminated by say sunlight which is off-axis, it will produce scatter, noise, into the image.

The ‘false stars’ seen during the flyby must have been sun illuminated dust.

Its far less obvious what could produce a ‘false star’ post flyby; it doesnt actually say tthat; it says “hundreds of ‘false stars’ were registered and it took almost 24 hours before tracking was properly re-established.”. This may simply indicate the complete return to normal mode, resetting & calibration etc etc, not that there were continuing ‘false stars’.

Provided the camera doesn’t rotate, taking the the respective darkest pixel of two images would be sufficient.

Difficult are slow-moving grains.

You may try some bundle-adjustment, but this gets expensive in terms of computing with too many dust grains.

In a future release, exploiting the spectra of the stars could help.

Best news must be that the team could reestablish contact with Rosetta. It cannot have been easy even until started rendezvous with 67P. But I suspect, or I do believe, that such difficulty must be something deeply connected with the very reason why the Rosetta team have wanted to bring their spacecraft into such location. “A harsh place” as the “grandfather” described it. Instead of keeping to stay some hundreds of kilometres away from it. May be a kind of another test for the operators. I really hope they can manage it.

A true adventure we are in!!

What a reminder that flying around activating comet is risky business. Luckily the probe was recovered, *phew*.

I hope best of luck for the operators.

Memory/kinetic-sensing exercise:

-Point with your extended arm to an object in your wall, library, etc.

-Close your eyes.

-With your other arm move the first one at different directions and distances, 10, 20 times.

-Open your eyes.

Where are you pointing now? This is how a [mechanical] gyroscope/attitude-control accumulates error. Error on laser gyroscopes are another kind.

Should say:

-With your other arm move the first one at different directions and distances, 10, 20 times. Turn back -keeping eyes closed- your arm to original position, after each movement.

“…Attitude is maintained using two star trackers, a Sun sensor, navigation cameras, and three laser gyro packages”.

https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraftDisplay.do?id=2004-006A

So, there is working software to manage attitude with the cameras. Is a ‘panic’ module up there, on Rosetta’s code? Is it fully managed at the Earthly Bridge, after download?

Rosetta, like many spacecraft, includes omnidirectional antennas. These enable low data rate communication with the craft if pointing of the high gain antenna is lost.

So there is a way to regain control, even if pointing of the ‘big dish’ is lost.

Ex web:

“Communications will be via the high-gain antenna, a fixed 0.8 meter medium-gain antenna, and two omnidirectional low gain antennas. Rosetta will utilize an S-band telecommand uplink and S- and X-band telemetry and science-data downlinks, with data transmission rates from 5 to 20 kbits/s. Communication equipment includes a 28 W RF X-band TWTA and a dual 5 watt RF S/X band transponder.”

Flyby status can [dramatically for the good or the bad] change in minutes range. On the bridge computing valid only for assessment.

Big hopes on Rosetta’s Coders evolving to this wild situation.

Say Good Look. Say a pray. Don’t touch those controls! 😉

Could be possible to the People on the Bridge to intervene in developing flyby situation.

On arriving new instructions from People on the Bridge, Rosetta has to ask herself: Has any strong quake happened since last download? If not, execute. If yes, abort and send new data set.

Well Emily strictly speaking the spacecraft does not take any measures. It is a machine responding to the programmed software. Maybe the engineers should also reappraise the parameters set for initiation of safe mode if it was a navigational confusion which did not actually place the craft in any danger. Jumping unnecessarily into safe mode also removes much of the capability for manually recovering the situation, therefore making things worse.

Whilst I am sure they will re-appraise, the whole point of safe mode is to give the best possible chance of recovery.

With a two way delay of some 40 minutes, plus decision time, and potentially very low data rates if high gain antenna pointing has been lost in the mean time, the spacecraft software has to call the shots in real time.

Its easy for us with 20:20 hindsight, lots of time, & a roomful of people to say ‘there was no danger’; Rosetta, with limited computing & sensing, & potentially unknown & unforseen events, doesn’t have that luxury.

The survival of the craft is *far* more important than loss of data in a given manoeuvre.

In safe mode you could still operate manually, provided communication works.

The main risk for instruments is pointing towards the Sun due to incorrect attitude. Therefore it’s better to close covers, and switch to safe mode.

The ESA spacecraft controllers knew that they’d have difficulties at some time or other with the attitude of Rosetta in reference to 67P.

The confidence with which they solved the problems and the expertise they used into getting Rosetta back on track in commendable.

I know they have a colossal amount of planning and shall I say ‘squabbling’ among the different disciplines to squeeze as much scientific data out of the time available as possible.

Cool heads and leadership will be important now. They will be thinking of the longer term goals.

Well done ESA…keep on keeping on!

If there’s dust on the lenses, just rotate the craft a little and any stars that haven’t moved are dirt, which could be filtered out in software. Doesn’t seem too hard to eliminate those.

What’s the FOV of the tracker camera lens?

If there is dust floating about, wouldn’t it also exhibit parallax against the background, so could quickly be excluded too?

Pity there’s not something bigger that wouldn’t get poor Rosetta confused.so much. Surely our own star might be of use, if the instrumentation would allow it?

I think it does have a sun tracker, but couldn’t confirm that.

But the problem is then your sun tracker has to be pointing at the sun, constraining spacecraft orientation, when you want the spacecraft pointing it’s cameras at the comet. In contrast there are stars to track whichever way the star tracker points.

People keep forgetting that dust on the lens is out of focus; it neither ‘silhouettes’ things nor causes simple false stars.

Another interesting question is what sort of accuracy a sun tracker might achieve; the sun has a large angular diameter (~31minutes, ~9mR) & fuzzy edges, a star is a point source. But the sun is *bright*.

There is very recent literature on this, eg:

Multiplexing image detector method for digital sun sensors with arc-second class accuracy and large FOV

By: Wei, Minsong; Xing, Fei; You, Zheng; et al.

OPTICS EXPRESS Volume: 22 Issue: 19 Pages: 23094-23107 Published: SEP 22 2014

They claim arc-second, around 5uR is possible; thats around diffraction limit for a 10cm aperture, so I guess *of the order of* what a star tracker might achieve. Useful 105degree FOV, reducing the orientation constraint.

Of course the sun tracker has far better signal levels; the star tracker analysis needs to include noise. There is a good article here:

https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?arnumber=1008988

This suggests declination noise ~~10uR RMS or so, significantly worse in roll (I havent taken the time to figure out why)

But as the sun tracker publication is late last year, it would appear sun trackers with accuracies challenging star trackers are recent & a challenge.

Wandering in the future:

Sky -as a conjunct- has a definite image [in the life span of a mission], and image recognition software is already mature.

Could bring resilience the aggregation of a ‘sky image recognizer’ on future missions.

Should be lots of ways to build those, I imagine of this:

2 or 3 array sensors. Noise insulation on the cell level. Differentiating monochromatic filters over each array.

(Don’t forget hot gas defrosting/cleaning system over the lenses).

Which are the 3 wavelengths bringing us the more ‘psychedelic’ image of the universe? 😉

By ‘compositing’ the 3 monochromatic images, could provide additional function, as NAVCAM.

Lots of people are re-engineering star trackers ‘from their armchair.’

Star trackers are routine commercial items made by several firms and used on many satellites; they are absolutely mission critical; but relatively cheap, highly optiimised, design off the shelf items.

A satellite has very, very strict mass and financial budgets to meet, and a launch window to hit.

So sure you could design some special purpose star tracker more resiliant to the presence of dust. You could use the spectrum, motion, parallax, focus maybe. You’d have had to do it *knowing almost nothing* about that dust, its density, particle size, velocity when Rosetta was designed. You might have to sacrifice performance, it will almost certainly weigh more, it will be untested in flight, so maybe you’d better have a conventional backup as its mission critical; which scientific instrument do you throw out to meet budgets?

Designing new ‘dust resistant’ star trackers ‘from your armchair’ is a bit easier than doing it for real.

You’re right, Harvey. Just having ‘armchair’ fun 😉 On the other side. Seems there isn’t a lot ‘of-the-shelf’ star trackers optimized for ‘dirty’ environments.

Most of space is pretty clean; it’s just near these pesky comets……. 🙂

I could throw out the second, twin star tracker…

Harvey: Agree with you, but no harm thinking armchair. I read that someone was suggesting to Nasa a probe to track Io’s volcanoes. Maybe they should think about their star trackers getting confused?

True; I guess I spent too long fighting mass, power and cost budgets for a spacecraft (which was never built) a few years back to find it an ‘armchair subject’ 🙂