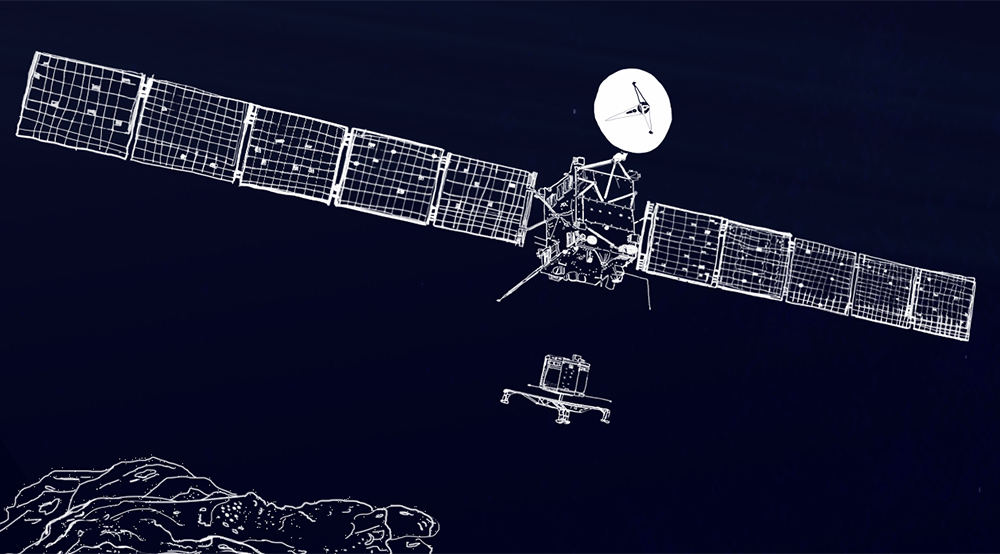

With the incredible images of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko’s nucleus grabbing most of the attention over the last few weeks, we shouldn’t forget about the comet’s coma. Of course, you can still find the most recent image of the nucleus later on in this blog post, but first let’s talk about coma and activity.

In case you are only just joining Rosetta on this unique journey and perhaps discovering the fascinating world of comets for the first time, a comet’s coma is the dust and gas envelope that grows around its nucleus as the comet moves along its orbit and progressively closer to the Sun.

The increasing warmth from the Sun causes surface ices to sublimate (change directly from a solid to a gas), and the gas escapes from the rock–ice nucleus. As the cloud of gas flows away from the nucleus and out into space, it also carries tiny dust particles: together, these slowly expand to create the coma.

The warming continues and activity rises as the comet moves ever closer to the Sun, and the coma grows larger, up to a million kilometres in diameter in some cases. Eventually, pressure from solar radiation and the solar wind causes some of the material to stream out in the opposite direction to the Sun, to form two tails, one made of gas/plasma and the other of dust. When the comet moves away from the Sun and returns to the outer Solar System again, the activity and the resulting coma and tails all fade away.

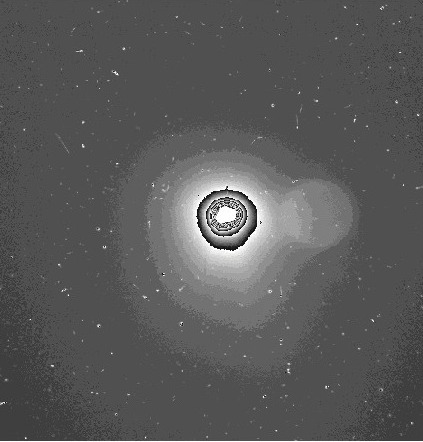

OSIRIS wide angle camera view of 67P/C-G’s coma on 25 July. Credits: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA

Today, comet 67P/C-G and Rosetta are between the orbits of Jupiter and Mars, about 544 million kilometres from the Sun. It is still a year before it reaches perihelion – its closest distance to the Sun – on 13 August 2015 at 185 million kilometres, between orbits of Mars and Earth.

Rosetta is meeting up with the comet now though, so that we can not only study how the comet warms up along its orbit and how activity develops, but also because it is much safer to learn how to operate in such a new environment when the activity is relatively low. Moreover, landing would be significantly more challenging any closer to the Sun, when activity is expected to be much higher.

So, on to the first of today’s new images. It was taken with the OSIRIS wide angle camera (WAC) on 25 July from a distance of around 3000 km, and with an exposure time of 300 seconds. The image covers an area of about 150 x 150 km. The grey scale of the image reflects the brightness and thus the density of the coma, with more particles close to the nucleus and fewer further away.

A significant challenge in imaging the comet in this way is the bright nucleus that outshines the surrounding coma. Because of the extreme range in brightness, the grey scale has been ‘wrapped’ several times close to the nucleus, but the centre is obscured by over-exposure. While OSIRIS is designed to deal with a controlled overexposure in the region of the nucleus, light from this strong source can cause artefacts by the optical system. For example, the hazy bright circular structure to the right of the comet’s nucleus is one such artefact. Also, stars are seen in the background, along with some ‘streaks’ due to cosmic rays hitting the detector.

Earlier in the year, OSIRIS witnessed a distinct rise in the activity of the comet, showing a coma spanning more than a thousand kilometres around the nucleus. That activity died away again, but nevertheless, this new image clearly reveals an extended coma close to 67P/C-G’s nucleus, where particle densities are highest; it very likely extends much further into its surroundings.

Using the data collected on Rosetta’s approach to the comet, the OSIRIS team are assessing in more detail the behaviour of the comet’s activity. To this end, data obtained from different distances and with different exposure times need to be correlated. This on-going work will also allow the team to determine whether there are any localised spots of activity on the comet’s surface, and how this correlates to the overall development of the coma.

For example, the apparent asymmetric nature of the coma likely results from a combination of the nucleus being an irregular shape and the activity being unevenly distributed across the surface. Furthermore, as the comet rotates, different portions are illuminated with sunlight at different times and, depending on the surface composition, the sublimation rates will vary accordingly.

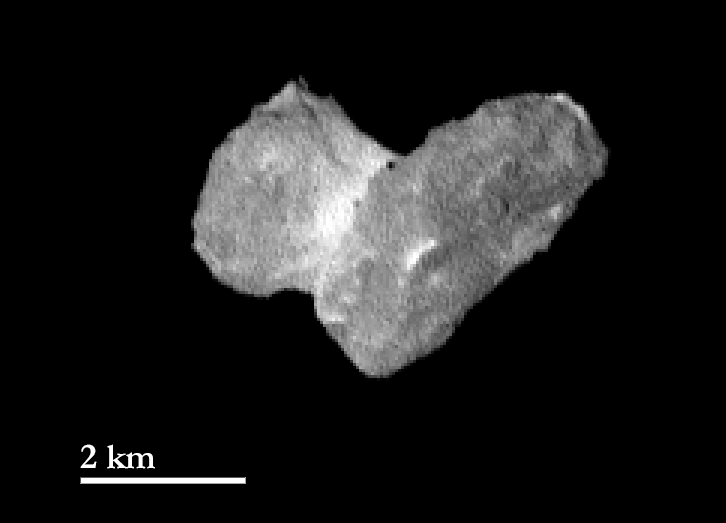

OSIRIS narrow angle camera view of 67P/C-G from a distance of 1950 km on 29 July 2014. Credits: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA

Meanwhile, the latest narrow angle camera (NAC) view continues to reveal more details regarding the comet’s surface. Taken on 29 July at a distance of 1950 km, one pixel corresponds to about 37 metres. Still clearly visible is the bright ‘neck’ region connecting the two lobes of the nucleus, along with several other discrete bright patches. The reason for these features is still subject to much discussion – they could be due to differences in material or grain size, or to topographical features, for example. A dark spot close to the neck is most likely a shadowing effect. The large surface depression discussed in last week’s image is still apparent at the very ‘top’ of the smaller lobe in this orientation.

This time next week, Rosetta will be within just 100 km of the comet’s nucleus and detailed mapping can begin in order to assess candidate landing sites for Philae. The first OSIRIS image from Rosetta’s rendezvous with the comet on 6 August will be presented during the main arrival event being held at ESA’s spacecraft operations centre in Darmstadt, Germany and published across all ESA channels. Exceptionally, special rapid downlink and processing will be used to make the image available as soon as possible: normally, data are stored on-board and only downlinked typically a few days later, when spacecraft operations permit. For an overview of the programme, including details of how you can watch the transmission via livestream from ESA’s spacecraft operations centre in Darmstadt, Germany, please revisit the recent ‘Call for Media‘ for Rosetta’s comet rendezvous.

Discussion: 18 comments

WOW, the detail is incredible.:)

Looks like the the more elongated lobe is layered?

The bulbous lobe appears as is it is ronded rather than just a sublimated piece.

Dear Emily,

I follow this blog quiet a while and would like to thank all participants for their effort. Its getting better every day, as we see pictures at least from NAVCAM on a daily basis.

As a live stream always is the most thrilling event, please give us some more detailed Information on the programme, that is actually streamed via the web upon august 6 ?

What ‘press briefings’ are streamed?_ Is this only the briefing dated 13:00h? Or can we hope to see more of the event (10:45–11:25 First scientific findings , 11:25–12:00 Mission operations and expected arrival at the comet) live?

Is it possible to ask questions by mail?

I think most of the space aficionados would like to see the WHOLE event beeing streamed live. It was great to witness Rosetta waking up live on the stream in january.

Please share these great moments with us in the weeks to come.

Hi Thomas, you can indeed follow all of it via the livestream. The programme in the call for media is the best guide. For questions on the day I’ll get back to you – we usually use the #AskRosetta hashtag on Twitter but I appreciate not everyone uses that platform.

Absolutely stunning, thank you very much.

Wonderful photos. Thanks.

Hi emily,

this is great news. I am not so experienced with Twitter, but will try to learn it by doing.

Total fascination for me, since the ‘beginning’. I am REALLY looking forward to how the team will pick a landing place on this rather chaotictly rotating comet. I love ALL of this!

Emily, I meant to direct the ‘landing place’ question to you, once you have time to answer. 🙂

Hi Laurence, did you see the post earlier in the week about the latest shape model? https://blogs.esa.int/rosetta/2014/07/28/updated-comet-shape-model/ It has a few discussion points about how and when the landing site will be selected. Once the nucleus can be imaged and studied in higher resolution (not long now!) then the teams will be working hard to select candidate landing sites. Stay tuned!

The nucleus looks like containing two rocks connected with a bridge of ice, which may be the remains of the ice that covered the rocks and it is somehow protected from erosion due to its position between the rocks. I think eventually it will sublimate completely and all that will remain is a double asteroid. What do you think?

Andreas : when ISON reached its perihelion last November it was very close to the sun. Sublimation was the reduction of water, hard rock, every complex molecule therein (including perhaps the molecules of RNA/DNA), reduced to simple molecules and blasted away from the sun by the solar wind. BUT with 67P having its Perihelion so far away from the sun, I do not believe sublimation will occur – ie it will survive the perihelion as it has done so many times (ie every 7 years) . Gravity effects through will squeeze the body and cause the particle ejection in the form of limit tails. I wonder how old 67P is (ie how many times it has orbited). The spectroscopy results should tell us the source of the body (ie was it ejected from MARS or EARTH millions of years ago?

Could you publish a schedule of science observations?

How can one not worry about the electrical impact of getting so close? I’m remembering the space tether experiment, and when NASA hit a comet with a copper projectile. Very unexpected results.

Good luck team.

Imagine both lander and orbiter witnessing a separation. Now that would be cool 🙂 Great reporting team Rosetta.

I am interested in the speed of the Comet through space, Rosetta must match this speed so how is that done?

Clive

Hi Clive: On 6 August Rosetta will match its speed to that of the comet, which is travelling at about 15.3 km/s with respect to the Sun. For Rosetta, the vast majority of the is speed was gained through a series of four ‘slingshot’ flyby manoeuvres earlier in the mission, three by Earth and one by Mars. The last tiny fraction that was needed has been made up by Rosetta’s thrusters since wake-up from hibernation on 20 Jan.

How fast is the Comet travelling through space?

Rosetta must match thsi speed and how is that done?

Clive

I read “……………..comet 67P/C-G and Rosetta are between the orbits of Jupiter and Mars, about 544 million kilometres from the Sun. It is still a year before it reaches perihelion – its closest distance to the Sun – on 13 August 2015 at 185 million kilometres, between orbits of Mars and Earth”. Have I understood this correctly that unlike ISON which reached closer to the SUN than Mercury, when the perihelion occurs a year from now, 67P will still be between EARTH and MARS. This could mean we will get a bright visible tail. ISON was hard to see because of its closeness to the SUN.