It’s burn week in space again, and Wednesday, 2 July, marks the start of a fresh set of four orbit correction manoeuvres (OCMs), referred to as the ‘Far Approach Trajectory’ burns. These will be somewhat smaller than those previous but will be conducted weekly, rather than fortnightly.

First, a quick recap to bring you up to date.

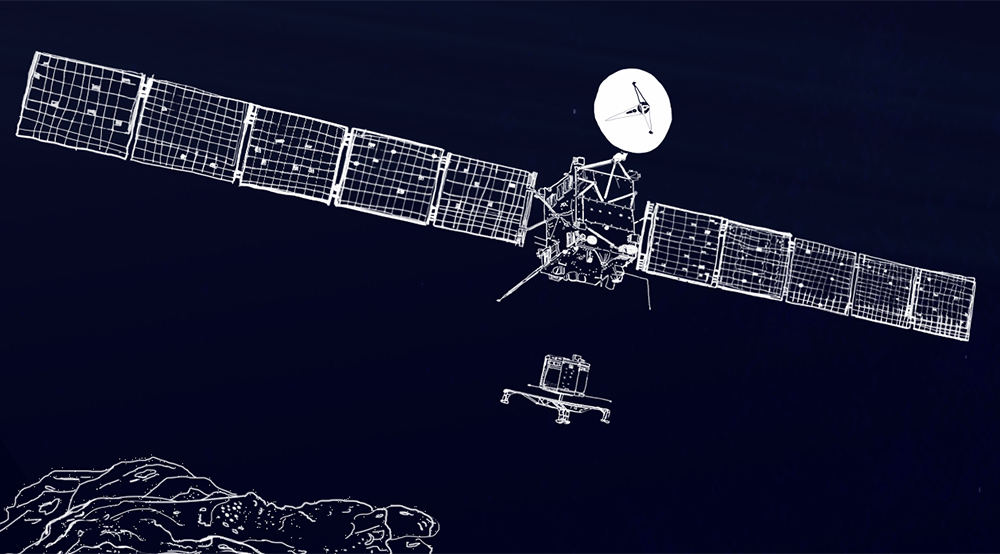

On 7 May, Rosetta began a series of ten OCMs designed to reduce its speed with respect to comet 67P/C-G by about 775 m/s. The first, producing just 20 m/s delta-v (‘change in velocity’), was done as a small test burn, as it was the first use of the spacecraft’s propulsion system after waking from hibernation on 20 January. The system worked fine!

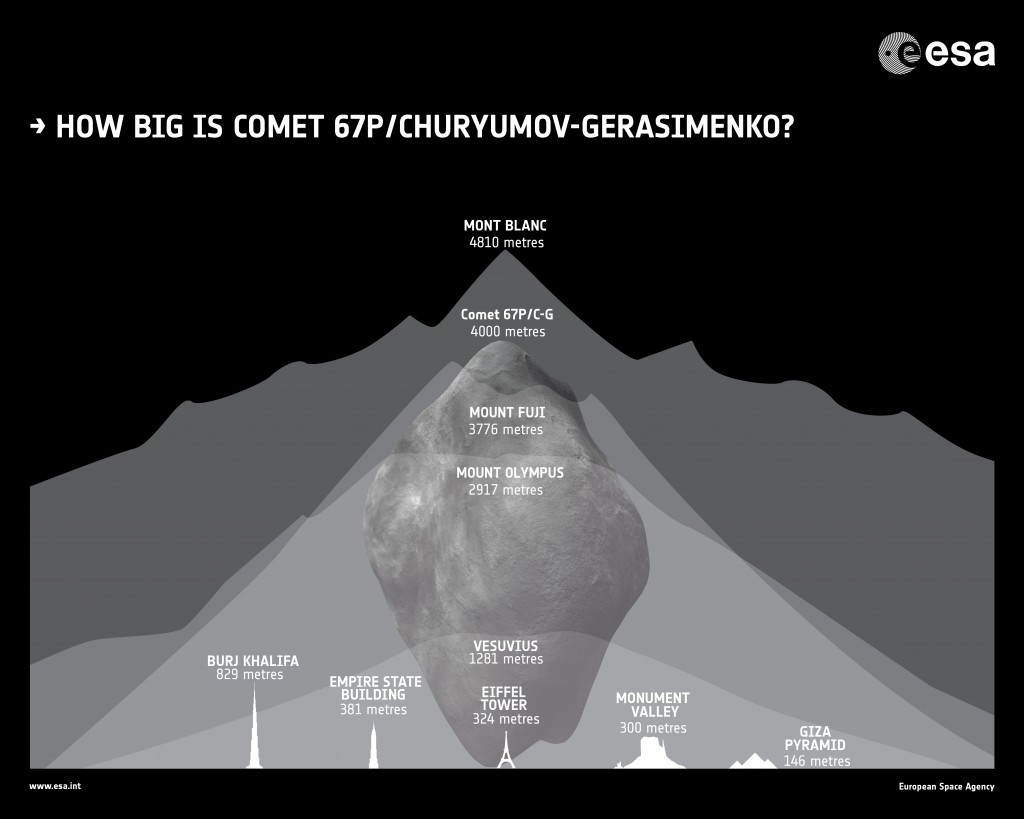

Rosetta’s target comet, 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, is about 4 km wide. Here it is presented alongside some of Earth’s landmarks. Credt: ESA

The following three, referred to by the Rosetta mission team as the ‘Near Comet Drift’ (NCD) set (and nicknamed here in the blog as ‘The Big Burns’), took place every two weeks starting 21 May. These three also ran beautifully and delivered 289.6, 269.5 and 88.7 m/s in delta-v, respectively. They were, in terms of run time, some of the longest manoeuvres ever conducted by an ESA spacecraft.

Thus the first four burns have already delivered 667.8 of the roughly 775 m/s needed to slow down to a relative velocity smaller than 1 m/s when we meet the comet on 6 August.

“The OCMs conducted so far have delivered more or less the exact amount of delta-v needed; we’ve seen small over-performances of less than a percent, meaning that no replanning of subsequent OCMs has – so far – been necessary,” says Sylvain Lodiot, Rosetta Spacecraft Operations Manager (see table below).

Another aspect of the burns to date is the fact that, if a burn did not take place as planned (due to any sort of glitch on board Rosetta or on the ground), the team had a week (or more) in which to correct the problem and re-do the burn – tight, but doable in terms of technology and team-planning workload.

This is about to change.

Four Fatties

The next four burns are designated as the ‘Far Approach Trajectory’ (FAT) manoeuvres, and since your blog editors can’t think of any better nickname (and despite them being much smaller than the three Big Burns), we’ll just call them the ‘Four Fatties’.

Fatty1 gets underway on 2 July at 14:05:57 CEST (12:05:57 UTC), should run for 1 hr:33mins:13secs and is set to deliver a delta-v of 58.7 m/s (the next three, on 9, 16 and 23 July, are planned for 25.8, 11.0 and 4.8 m/s, respectively).

(The Four Fatties will be followed by two final CAT– for Close Approach Trajectory – burns, for the total of 10 OCMs; details on these later.)

But while the required delta-v’s are getting smaller, so, too, are the reaction times available to the Rosetta team if anything goes wrong with a burn.

“The next four FAT burns, in particular, are critical,” says Sylvain.

“If any one burn is delayed, we will have a window of just a few days in which to react, fix whatever caused the problem, replan the burn – which would invariably require even more fuel – and then carry it out.”

It goes without saying that handling any such replanned burn would require team work and expertise of the highest calibre.

But this is all theoretical for now; today Rosetta is working nominally and no one expects problems with the propulsion system for the Four Fatties.

The rest of the spacecraft’s systems – including power, thermal, attitude and orbit control, data handling and communications – are operating as expected.

Working behind the scenes: Flight dynamics

It’s worth mentioning the numerous teams – ‘teams of teams’ – working behind the scenes to ensure Rosetta gets to 67P/C-G. These include the Flight Dynamics experts, who are responsible, in general terms, for determining where Rosetta (and the comet) are and what attitude the spacecraft is in at any given moment.

Among other activities, the team are working on developing several mathematical models of comet 67P/C-G that can model and predict the gravity potential, the physical shape and rotation/spin, and the coma – the latter to predict how the comet’s outgassing will affect Rosetta’s orbits and Philae’s approach.

“We need a good coma model that tells us the density and velocity of particles being emitted from the comet,” says Frank Budnik, a flight dynamics specialists at ESOC.

“We expect the spacecraft to be affected by the coma on top of the comet body’s gravitational pull, and these all play into calculating the orbits and the thruster burns required to keep Rosetta near the comet.”

| Date | Delta-V m/s |

Dur. (mins) |

Comment |

| 7 May | 20 | 41 | Complete |

| 21 May | 290 | 441 | Complete |

| 4 Jun | 270 | 406 | Complete |

| 18 Jun | 91 | 140 | Complete |

| 2 Jul | 59 | 94 | |

| 9 Jul | 26 | 46 | |

| 16 Jul | 11 | 26 | |

| 23 Jul | 5 | 17 | |

| 3 Aug | 3 | 13 | |

| 6 Aug | 1 | very brief |

Discussion: 11 comments

How do you deal with (model..plan..implement) the large uncertainty in the comet’s outgassing pushing against the solar panels?

yeahhh… new post available !

We’ve waited a lot for this update, but it was worth.

A lot of information.

Question : you say that the over performance was globally about 1% for the 4 big burns.

Reading the table we can see that the first 3 one were almost perfect and that the fourth one gave a 5% over performance.

Do you know why this happen ?

Thanks again for this blog.

Serge

Per table at:

https://blogs.esa.int/rosetta/2014/05/07/thruster-burn-kicks-off-crucial-series-of-manoeuvres/

and table above…

May 07 burn – planned:20 m/s; actual:20 m/s

May 21 burn – planned:290.89 m/s; actual:290 m/s

June 04 burn – planned:270.98 m/s; actual:270 m/s

June 18 burn – planned:90.76 m/s; actual:91 m/s

My calc’ed ~errors: 0%, -0.3%, -0.3%, +3%

My math could be off but there’s messy rounding being done OR inaccurate or possibly outdated/estimated figures posted.

Were the burns to increase the spewed or decrease?

oops speed.

The purpose is to reduce progressively the speed relative to the comet. Now we are at 43m/s (about 150 km/h) and at the endo of the month will be only 8 m/s (30 km/h)

Brian,

The numbers don’t add up exactly because we’re updating the blog in real time, posting the immediate delta-v results that come from the flight control team (which are based on telemetry — which is sometimes inexact). In later posts, we have had time to get more accurate numbers from flight dynamics, who will have had time to do an orbit determination and that gives a different result — but we don’t go back and update the previous blog post(s) with the new numbers. I may just remove the table, because it isn’t totally correct. What I can say is that all the burns have been very accurate so far, typically with less than 0.5% difference compared to what was needed. Cheers!

Yeah,

Brian raises a gud question.

comming back to the question of SWL:

Were the burns to increase the speed or decrease?

Relativ to the comet the speed is decreased, but the comet is currently still faster than ROSETTA and therefore the spacecraft has to be accelerated on it’s orbit.

Hi Gunther:

The burns – all ten of them – are designed to bleed off ~775m/s of speed – that is, the relative speed between Ros & 67P.

Here’s what’s happening:

Rosetta is ahead of 67P as viewed from the Sun

The comet and Rosetta are both accelerating in their orbit about the Sun (both are in heliocentric orbit; both are approaching apohelion).

The burns are additionally accelerating Rosetta wrt the Sun (and the comet)

The comet is moving faster than Rosetta

The result is that Rosetta’s speed with respect to the comet is slowing

By 6 Aug, Rosetta will be almost at the same speed as the comet, in almost the same orbital path.

Hope that helps!

Yes, this is a good description.

Thanks