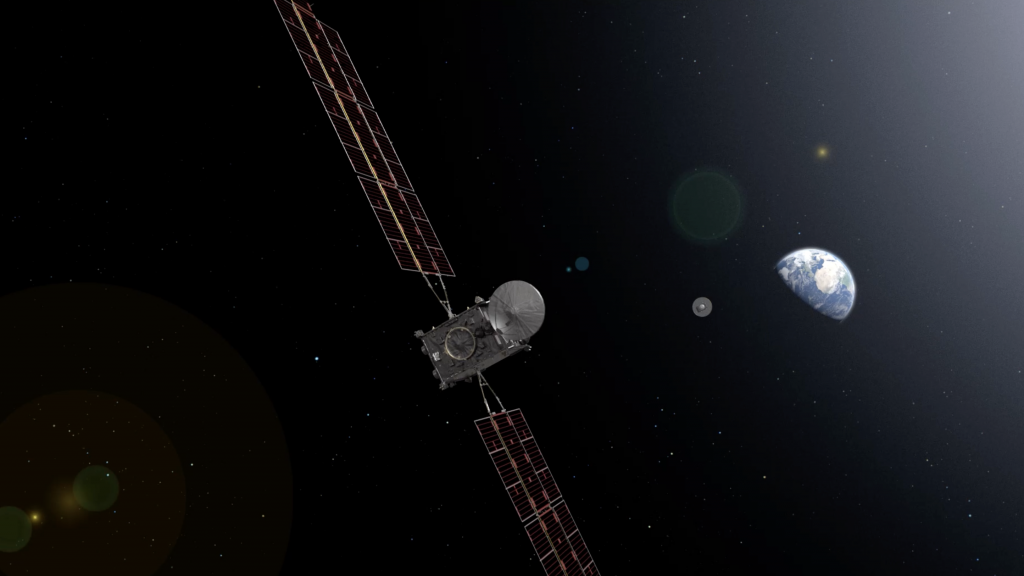

Equipped with radios, amplifiers and antennas, the Earth Return Orbiter will listen to the signals sent from Earth, and shout back its answers during its interplanetary journey. Here is a quick guide to the most talkative side of the first spacecraft to make a full round-trip from Earth to Mars.

By Edi Yau, ESA’s Earth Return Orbiter (ERO) Communications System Engineer.

You can think of the communication subsystem as the ears and the voice of the spacecraft. It must listen carefully to the signals transmitted from Earth to understand all the commands. It also needs to shout back at us, telling us what it is doing and what is going on.

I follow the design and development of the equipment used to communicate between the Earth Return Orbiter and Earth. That means the radios, the amplifiers, the antennas as well as all the networks linking them together.

The separation between Mars and Earth is massive. The furthest distance can be up to 403 million kilometres, or 2.7 times the average distance between Earth and the Sun; it would be like driving around the circumference of the Earth 10 000 times.

This is why we need to have very sensitive ears on the spacecraft. The orbiter has a large antenna of 2.2 metres in diameter – ERO’s big voice and ears. The receiver works within a certain range of sensitivity, and some signals might be too loud or too quiet. When the spacecraft is close to Earth, the signal is too strong for the large antenna. To make sure that ERO does not get deafened, we have a smaller antenna dish and two other low gain antennas that will allow us to talk to the spacecraft no matter where it is between Earth and Mars.

ERO needs to point its ears towards Earth to listen well, otherwise teams on the ground would need to talk even slower than normal when sending commands.

Because Mars is very far away from Earth, ERO needs to point very precisely towards Earth to send its message across the distance. To help that, the mechanism controlling the antenna has a pointing error of better than 0.4 degrees, or about half the distance between Earth and the Moon.

If you have trouble understanding this order of magnitude, this visualisation could help you.

Visual representation of the 0.4 accuracy scale for ERO as it gets further away from Earth. Credits: ESA – L. Logan

Back on Earth, ESA has massive antennas of 35 metres in diameter. Since we want to have good visibility towards Mars all the time despite the Earth’s rotation, we have three stations located in Spain, Argentina and Australia. If we would still have trouble contacting ERO, we could also get some help from our friends at NASA who have a 70-metre antenna that is part of the Deep Space Network.

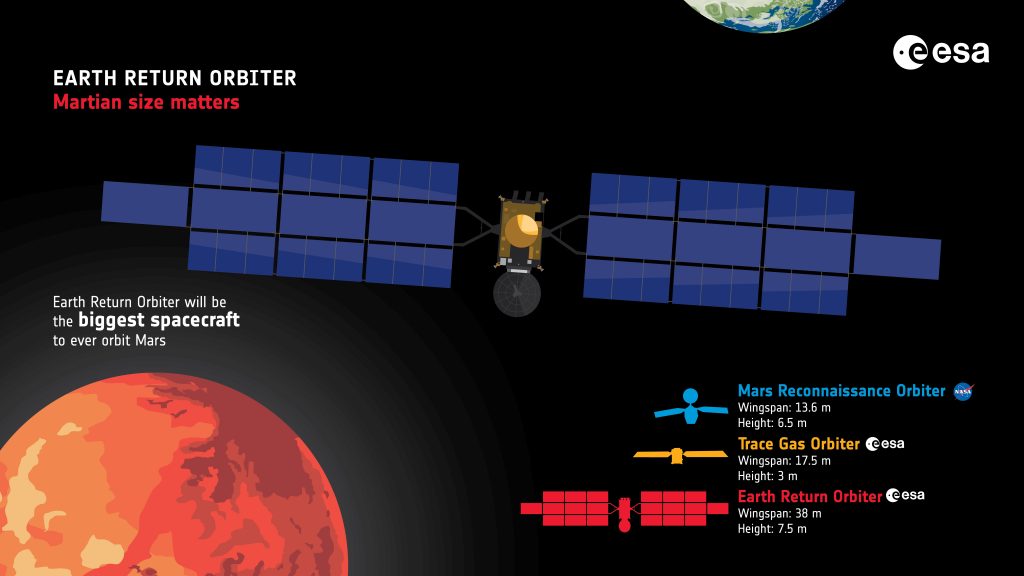

The European orbiter, the biggest spacecraft to orbit the Red Planet, will also talk to other human-made artifacts on the martian surface. ERO will be able to get in touch with ESA’s ExoMars Rosalind Franklin rover, NASA’s Perseverance rover and the Sample Return Lander. ERO will use an ultra-high frequency radio developed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory along with a compact antenna built by European industry.

Infographic showing the size of the Earth Return Orbiter in comparison with other martian spacecraft. Credits: ESA – K. Lochtenberg

Once orbiting Mars, ERO will act as an Olympic relay runner, collecting information from the martian rovers, sending it back to Earth as fast as it can while collecting commands from Earth in parallel and passing them back to the rovers.

Like any teleoperator or postman, ERO has to make sure each message goes to the right recipient at the right location and confirm it has been properly received. Once the message reaches its destination, it will be deleted… forever.

Composite image of ESA engineer Edi Yau emulating the communication delivery tasks of the Earth Return Orbiter between Earth and Mars. Credits: ESA – L. Logan

Learn more about the biggest spacecraft to ever orbit Mars: Earth Return Orbiter on ESA’s Earth Return Orbiter pages.

Discussion: no comments