In collaboration with le Parisien Magazine / Aujourd’hui-en-France Magazine

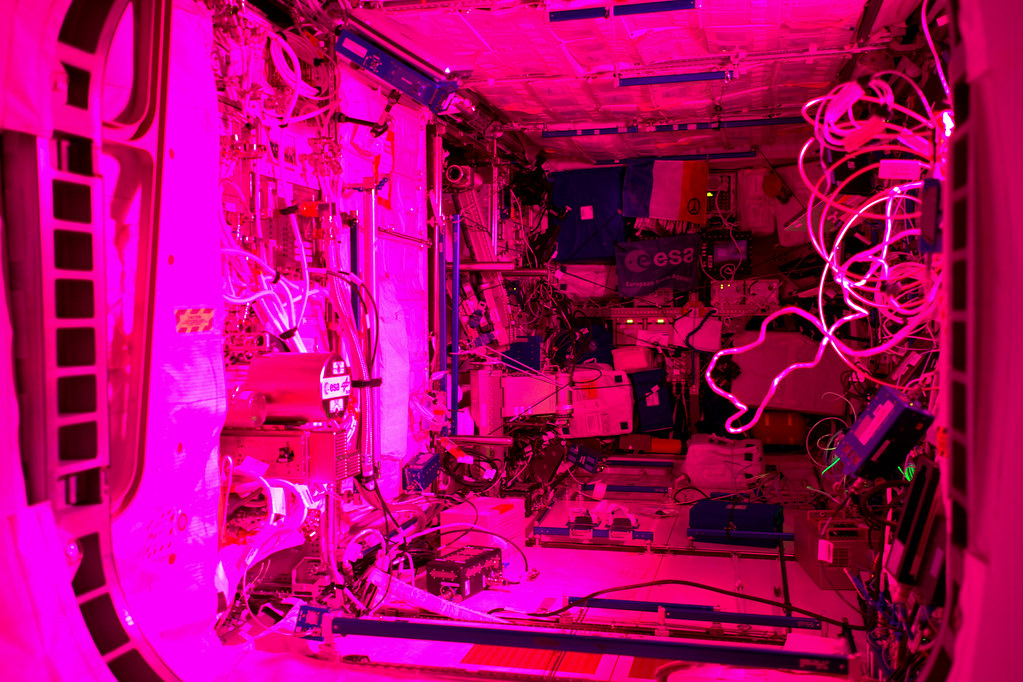

The Columbus module at night: no we’re not having a disco party, it’s a vegetable growing experiment!

It has been two and a half months since I landed on the International Space Station, and I have not yet written a diary entry about one of our main activities on board: scientific experiments. I see you grinning from here. It is true that, on paper, microscopes are less sexy than, say, spacesuits. But, unlike spacewalks, which occur only once or twice every six months, experiments occupy more than half of our time. This is our number one activity, ahead of maintenance and cleaning. Over the decades, the experiments carried out in the Station have always proven very useful. For starters, they allow us to dream of conquering space. Before imagining going to Mars, we must invent the techniques and technologies that will allow us to endure such a trying journey. How do specific body parts react to being deprived of gravity for such a long time? Does our equipment perform as we need it to? Before leaving for future missions to other planets, we have to check everything. That is our mission, and it will continue for several years before we embark on our journey to the unknown.

Moreover, we make sure that our home planet benefits from our excursions to space. Medicine, biology, physics, materials science, the study of fluids… Our work in the Space Station touches on many fields, because weightlessness allows us to perform experiments that are impossible to put into place on the ground. In space, for example, bacteria are in principle much more virulent, so we take several strains of bacteria with us to subject them to the space environment, and observe them. Some grow and multiply but there are others, that, strangely, do not. This leads to the conclusion that if a bacteria does not ” change” more than it does in space, there is virtually no chance of it being dangerous on Earth and automatically becomes a serious candidate for a future vaccine. Other examples are experiments related to the brains of astronauts. A few years ago, scientists realised that after a certain age, adults no-longer benefit from “hard-wired” learning such as when a child learns to bike or swim. But there is one exception: us astronauts.

This phenomenon occurs during the first few hours when you learn to move in weightlessness. The transition to a state of floating, while somewhat destabilising at first, causes a mysterious connection to be made in our brain that eases us into microgravity –until the end of our lives. Because this type of learning is rare, scientists on Earth ask us to do a whole bunch of tests on our brain. They recover the data to make enormous advancements on the functions of the brain that are as yet unrecognised.

Regarding scientists, I have always disliked the cliché of old bearded men with test tubes. Without them, we would not be able to do our work. They are the ones who help us out with our experiments. They are also the ones who process the data we collect and try to draw concrete conclusions from it. In fact, it would take me a hundred years to gain their combined knowledge in the sciences – all astronauts rely on them a lot.

I enjoy running the experiments. Of course, there are some that I prefer. The other day, we used robotic arms to deploy micro-satellites the size of a Rubik’s cube. That was pretty cool! Other experiments involve giving some blood or inflicting small electric shocks. Naturally, they are much more uncomfortable but the gains to be drawn from our research in weightlessness are worth it.

The MARES experiment – the machine sends electrical shocks to monitor my muscle’s reaction

Discussion: 22 comments

Bonjour Thomas,

Moi aussi j’ai dejà écris sur vos expériences …parce que je me prend à rêver qù’elles vous mèneront à pouvoir re-écrire l’ADN et permettre à des femmes comme moi d’éviter l’anomalie génétique et d’avoir olus de chance d’échapper au cancer du sein. Ce sera trop tard pour moi mais pour les générations à venir… merci pour tout ce que vous faites… voici mon rêve, mon article : https://leblogdemaryena.strikingly.com/blog/reve-d-espace

Merci de tout coeur.

Bien à vous Marie

J’espère que beaucoup d’expériences scientifiques

réussiront.Les scientifiques pourraient s’inspirer

des artistes pour éviter aux malades des traitements

violents.L’humilité ,la compassion,l’empathie,ses valeurs que la médecine devrait plus souvent partager

avec les patients et les astronautes qui leur servent

souvent de cobayes.Merci, Thomas pour tous ses sacrifices pour la recherche.

Bonsoir Thomas,

Merci pour ce nouvel article des plus passionnant. Ah, genial de la science 😉 !

En meme temps, on est deja tellement comble de joie et de bonheur, grace a tout ce que tu partages avec nous que l’on ose esperer davantage.

Pourtant et bien oui, tu continues a nous surprendre chaque jour et ce, depuis le premier jour. C’est vraiment fabuleux !!!

On devrait tester quelques cerveaux, parmis nous tous qui te suivons chaque jour.

Car on se sent si proches de toi, nos vies sont tellement rythmees par tes journees, les emotions que tu sucites en nous, tes photos etc, que l’on pourrait presque ressentir la sensation de flotter. Comme dans un reve eveille.

Encore mille fois merci, pour ce lien indestructible, lui aussi, que tu as cree avec nous :).

Bonne nuit Thomas et a tres bientot.

ProximaNath.

C’est passionnant ce que vous faites là-haut !

Et c’est quand le prochain bus pour l’ISS ? 😉

Merci Thomas pour vos commentaires très instructifs. J’espère que vous publierez un livre avec vos superbes photos lors de votre retour sur terre.

Merci Thomas pour ces explications simples et claires.bon courage pour la suite à toi et tous tes collègues de la station. Le peuple terrien à besoin de vous.

Bernard.

Toujours passionnant ! Merci Thomas Pesquet !

Merci de nous faire partager ce que vous réalisez. Je ressens à travers vos post sur FB la passion que vous vivez.

une question : Puis-je apercevoir l’ISS depuis chez moi en Vendée à 10km au nord de La roche sur yon ?

Oui tu peux télécharger l’application ISS Finder et suivre où il se trouve. Par exemple en ce moment l’équipage se trouve au dessus de l’océan indien !

Merci pour cet article, ces explications et descriptions passionnantes sur votre activité dans l’espace ! Je crois que des milliers de personnes apprécieraient un livre de compilation de vos articles et photos à votre retour sur Terre! Vous mettez l’espace et les étoiles à portée de tous les terriens!

Vous cultivez des légumes… Ça m’intéresse. Ils se mangent, se fument, se chiquent ? Mais vous êtes peu locace concernant votre activité de jardinier… Secret défonce ? ;D

C’est très passionnant! Merci pour toutes ces expliquations, c’est instructif et enrichissant.

I Absolutely Love Space and the Unknown!! Tell me More!!! Thank you for Sharing!!

Hyper cool les expériences en tout cas se que tu fais est passionnant !

Lilou 10 ans , ta plus grande fan❤

“si cette bactérie ne « s’agite » pas plus que ça dans l’espace, il n’y a quasiment aucune chance qu’elle soit dangereuse sur Terre”. Si te plait explique nous pourquoi elle serait moins dangereuse sur Terre que dans l’espace? S’il te plait!?

🙂

merci pour ttes ces explications . bonne continuation

bravo à tte l’équipe de l’ISS

Thomas, en vous suivant quotidiennement vous me permettez de rêver, de voyager, de me cultiver. Bravo pour vos talents ainsi que celui de rédacteur 😉 Merci pour votre partage avec nous ! Pourriez-vous essayer de nous faire une photo de Toulouse by night ? Belle aventure à vous ! Christelle M

Thomas, une fois de plus tu nous présentes un excellent article de vulgarisation sans que cela soit rébarbatif. Et que dire de ces expériences scientifiques qui aboutiront peut-être à d’énormes progrès médicaux. Merci Thomas. Ah, au fait, tu nous parles de Mars, alors peut-on s’imaginer te voir un jour marcher sur la planète rouge, comme jadis l’a fait Neil Armstrong sur la Lune ?

Thank you so much for this scientific article, dear friend. My best wishes to you for your upcomimg science programs.

This content is very interesting. Thank you for this story

Thank you for this story