Prof. Jean Pierre Bibring (Philae lead scientist and Principal Investigator CIVA), Dr. Stephan Ulamec (Philae Lander Manger, DLR),

Dr. Wlodek Kofman (Principal Investigator CONSERT), in conversation with moderator Monika Jones. (image (c) ESA/J.Mai)

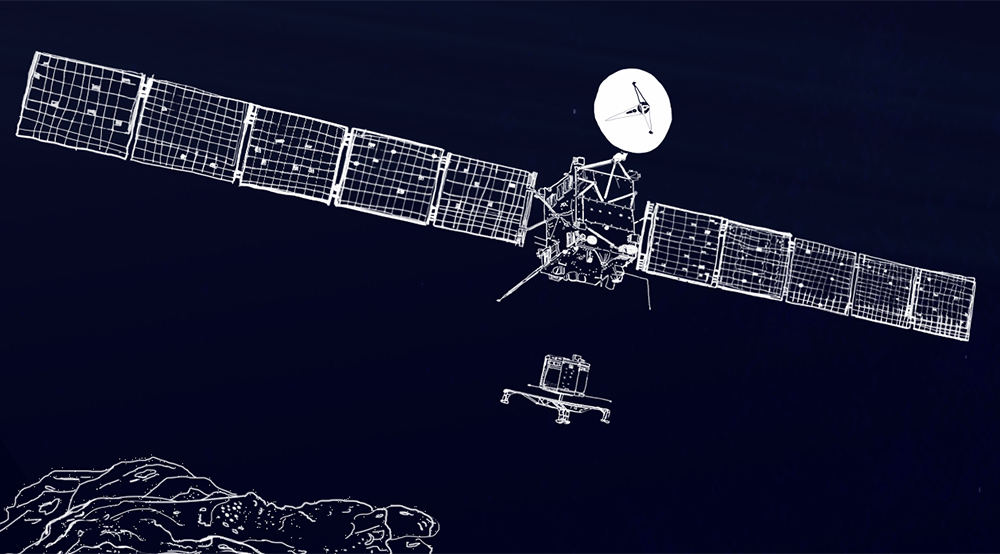

Did you know that Rosetta might have had two passengers? As the mission was developed, the plan evolved from having two landers to one, Philae. Preparing a lander for a daring mission never attempted before took time, and great attention to detail.

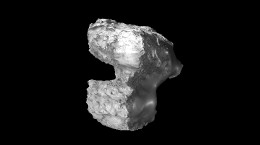

“The risks are huge,” said Jean Pierre Bibring, Philae Lead Scientist and Principal Investigator CIVA/ROLIS. “We had to develop something to land on something that was unpredictable and unknown. We did our best to predict all the eventual circumstances but there are many. If the comet is very active we will never be able to go very close to just to set down the lander. The comet has to be cooperative.”

“When we designed the lander, the discussion was where will we land – on a crust, on snow, how deep will we go inside and how far down will we go?” said Wlodek Kofman, Principal Investigator CONSERT.

Much more information about the surface of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko will be gathered by Rosetta before Philae is deployed. The team cannot yet be sure what challenges it will face.

“Our big fear when we were designing Philae was a very hard surface and bouncing. So we have all kinds of damping mechanisms, screws in the feet etc. to help us stay on there. The surface might also be very loose regolith so then you have to consider the danger of sinking into the material,” said Stephan Ulamec, Philae Lander Manager for DLR. “The problems we envisaged with the surface on landing changed between design and now, and will probably change again when we are closer to the landing.”

Philae will conduct a range of experiments, including drilling into the surface of the comet.

“One of the key resaons to have a lander is to find the material that has not been modified by outgassing,” said Ulamec. “COSAC is an evolved gas analyser where samples taken from the drill will then be heated and the gases will be brought to mass spectrometers to really get the composition, the general and isotopic compositions, to find out what is this comet made of.”

Prof. Jean Pierre Bibring (Philae lead scientist and Principal Investigator CIVA), Dr. Stephan Ulamec (Philae Lander Manger, DLR),

Dr. Wlodek Kofman (Principal Investigator CONSERT), in conversation with moderator Monika Jones. (image (c) ESA/J.Mai)

The experiments conducted by Rosetta and Philae will mark a new departure for cometary science. “This time we will have direct measurements coming from the surface. We have the measurements from the orbiter, from the remote sensing and then from the surface. To really see the interior we needed two things – the orbiter and the lander. We will be transmitting the radio waves through the comet, and doing this we learn what is inside the comet,” said Kofman.

It will be a long year for the Philae team, building up to the planned landing in November. But whatever the lander achieves it cannot come back to Earth.

“Philae will not return to Earth,” said Stephan Ulamec, “but will have a nice retirement on the comet.”

Discussion: 2 comments

it’s diffrent

Try using the rocket motor on the lander to change the rotation of the comet and get more light on solar panels.