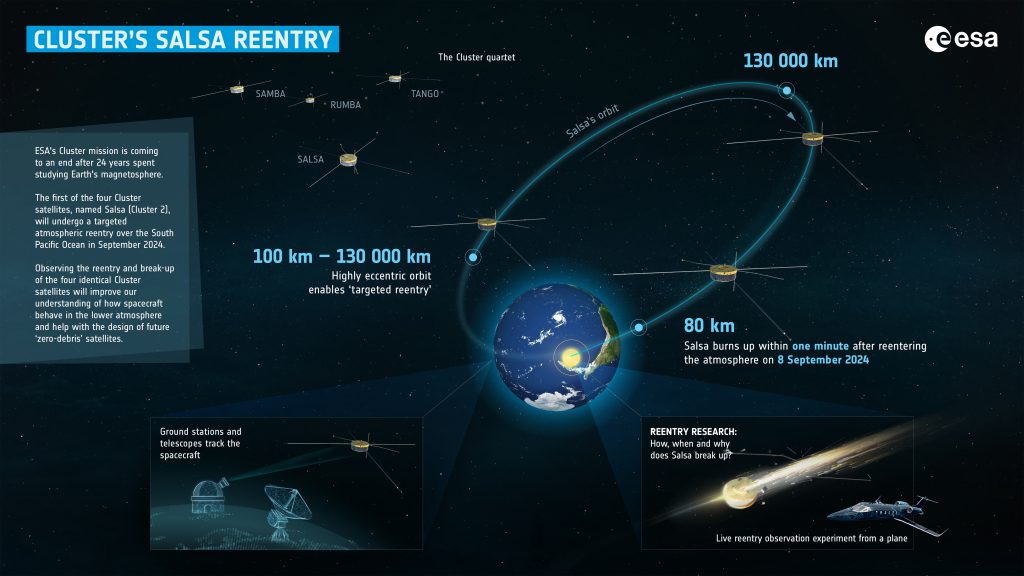

On 8 September 2024, Salsa (Cluster 2), one of four satellites that make up ESA’s Cluster mission, will reenter Earth’s atmosphere over the South Pacific Ocean Uninhabited Area.

Salsa’s orbit takes the satellite quite far out during each of its 2.5-day orbits. As it moves away from Earth to its apogee (farthest point) at around 130 000 km and then comes in close again, it moves in a similar fashion to near-Earth objects like asteroids in the vicinity of our planet.

Its asteroid-like behaviour makes observing the satellite to determine its precise location and trajectory the ultimate job for our in-house asteroid hunters within ESA’s planetary defence team.

You might wonder, can’t you point the radio antenna to the satellite and simply measure where it is?

The answer is yes, for now. Through ESA’s Estrack ground stations, the flight control team are in contact with the satellite on a regular basis. They use a special radio tone that is echoed by the spacecraft to determine how far away it is, while the Doppler variation on the radio signal is used to determine its speed. This data is called radiometry. However, it is getting increasingly difficult for Salsa to keep the power on and use its radio.

As the reentry comes closer and the spacecraft dips deeper and deeper into the atmosphere with each perigee (closest point), it might stop responding before the day of the reentry. If it’s still possible, Salsa’s final radiometry measurements will come in during its last ground station pass with Kourou ground station, about two hours before its reentry.

The National Space Facilities Control and Test Center of the State Space Agency of Ukraine caught Salsa streaking across the skies in May. Credit: NSFCTC of the SSAU.

To complement Salsa’s radiometry, multiple telescopes are observing the spacecraft during its last weeks, reducing the uncertainty of its precise moment of reentry. It’s not easy catching an asteroid or a satellite in the small field of view of a telescope and pointing it correctly can be extremely challenging. If the object, in this case Salsa, is close to its perigee, it appears very bright in the sky, but it zaps by extremely fast. Once it is far out and closer to its apogee, it moves much slower, but is more faintly visible against a backdrop of stars.

Salsa passing through the centre as observed by ESA’s Optical Ground Telescope on 3 September 2024.

Near-Earth object telescopes that usually detect asteroids are now supporting Cluster observations, including ESA’s Optical Ground Station, located in Tenerife (Spain), ESA’s Test-Bed Telescopes and the Schmidt telescope at the Calar Alto Observatory.

Cluster is also the subject of a monitoring campaign by the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC), asking international partners to support the monitoring of the satellite reentry and share data.

Shortly before and during the actual reentry at 80 km altitude, the satellite will be out of range of Kourou ground station and too low over the South Pacific Ocean for a land-based observatory to track it any longer.

And yet, we’re attempting to still have our eyes on Salsa even then. A plane full of scientists and their instruments will perform an airborne observation experiment, hoping to catch rare data on the precise break-up process of a satellite during reentry. Salsa’s telemetry and the observations until the reentry are combined with the expert skill of our flight dynamicists to pinpoint where they need to be flying to be safe, yet as close as possible.

Leading up to and during Salsa’s reentry we are providing updates via the Rocket Science blog, and the @ESA_Cluster, @esaoperations and @esascience X accounts.

Discussion: no comments