#OTD – 14 January 2005

2017 marks twelve years since the historic touchdown of Europe’s Huygens probe on the surface of Titan, over 1.2 billion km away.

There’s an excellent retrospective report on the NASA/JPL website that provides a look back at the events of 12 years ago and highlighting the continuing progress of the Cassini mission, now on a magnificent, if sad, ‘Grand Finale‘ tour of Saturn. With fuel running out, its mission is set to end in September this year.

As part of its final ambitious observing plan, the craft began last month making a series of 20 orbits, arcing high above the planet’s north pole then diving down, skimming the narrow F-ring at the edge of the main rings.

Then, starting in April this year, Cassini will leap over the rings to begin its final series of 22 daring dives, taking it between the planet and the inner edge of the rings.

ESA are working with Cassini during the Grande Finale with crucial radio and gravity science support, using the ESA deep-space ground stations.

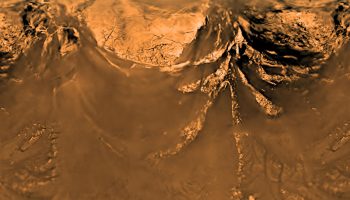

This poster shows a flattened (Mercator) projection of the Huygens probe’s view from 10 kilometers altitude (6 miles). The images that make up this view were taken on Jan. 14, 2005, with the descent imager/spectral radiometer onboard the European Agency’s Huygens probe. Image credit: ESA/NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

You can also read original and continuing updates on Huygens’ science results via the dedicated ESA webpages:

https://sci.esa.int/cassini-huygens/

https://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Space_Science/Cassini-Huygens

12 years ago

On 14 January 2005, science data collected by Huygens during its 2-1/2-hour descent (at over 600 km, Titan’s atmosphere is much thicker and denser than Earth’s) were relayed to Earth by the NASA-operated Cassini orbiter, which had given Huygens a lift across the Solar System to the enigmatic Saturnian moon.

You can follow, more or less, in real-time tomorrow when @esaoperations and @esascience will post updates in Twitter to highlight the brief but spectacular Huygens mission (keep an eye on @CassiniSaturn, too!).

Atmospheric entry was at 10:05 CET, and landing came at 12:38 CET. Due to the immense one-way light time, signals from Huygens relayed by Cassini were only received at ESA’s ESOC operations centre hours later, at 17:19 CET.

There, the first person to see the data start flowing into the mission control systems was Huygens Spacecraft Operations Manager Claudio Sollazzo, now retired.

Earlier this week, Claudio described that historic day:

Claudio Sollazzo during Huygens landing Credit: ESA

Due to the great distance, Huygens’ operations were pre-programmed and all of our work on the mission control side had already been done by the time the landing probe separated from Cassini on 25 December.

We really had not much to do on landing day, except wait for receipt of signal [acquisition of signal], so AOS was the crucial moment. We coordinated with NASA’s Deep Space Network antennas, to ensure receipt would go as planned. The main aim for us was to receive, then hand-over as soon as possible the scientific data to the scientists, many of whom were at ESOC, as quickly as possible. While this sounds straightforward, it was a big challenge. But it all worked. When we saw that the radio telescopes in North America and Australia had see the signals coming from Huygens, we began to suspect things had gone OK.

For me, the absolutely most fantastic moment was sitting on console in the Main Control Room at ESOC and seeing the first data start flowing into our mission control system. I couldn’t believe we had made it! Made it so far to an alien world! That moment – seeing the first images and knowing that 15 years of hard work were being paid back – will be in my heart forever.

Oops

It’s worth noting that ESA almost didn’t receive any data from Huygens!

A problem discovered only after launch – basically, an inappropriately selected parameter coded into the firmware on a radio receiver on board Cassini – would have affected communication between the Huygens probe and the Cassini spacecraft. This would have rendered the probe’s data unrecognisable due to the effects of Doppler shift in the probe data signal arriving at Cassini during Huygens’ descent.

The misconfiguration would have been trivial to fix prior to launch, but was impossible to reset once the craft were in space.

Boris Smeds Credit: ESA

An soft-spoken engineer at ESOC, Boris Smeds, was able to confirm the existence of the flaw only after pushing through an extensive series of tests that were initially rejected by mission managers as unnecessary.

Discovery of the flaw as Cassini and Huygens were cruising toward Titan kicked off intensive work involving hundreds of engineers at NASA and ESA, and resulted in a fix. Basically, the orbit of Cassini was redesigned to change the orbiter-lander geometry so that the emitted signal would be recognisable.

At the time, Boris, who had worked on recovering from pre- and post-launch telecom issues in several previous missions, said:

“This has happened before. Almost any mission has some design problem.”

“To me, it’s just part of my normal work.”

Discussion: no comments