We’re listening: Earth tracking the Schiaparelli lander 19 October

Today’s blog post was contributed by Thomas Ormston, a spacecraft operations engineer working here at ESOC, Darmstadt, Germany.

Since its successful separation on Sunday, 16 October, Schiaparelli has been free-falling toward Mars. At the moment the lander is asleep, save for a timer that will wake it up just before it arrives at the top of the Martian atmosphere on Wednesday, 19 October. While a lot has been shown about how it will land on Mars (see the cool, real-time video here), we wanted to tell you how we’ll listen in from Earth. The purpose of Schiaparelli is to teach us and provide experience with the technology Europe needs to land on Mars. That’s why, no matter what happens during the descent, it is critical to hear as much as possible about every step of the journey so we can maximise our learning from Schiaparelli. To do this, we have enlisted a network of helpers from all over the world (and off it!) that will record the signal as Schiaparelli lands.

First a bit of background.

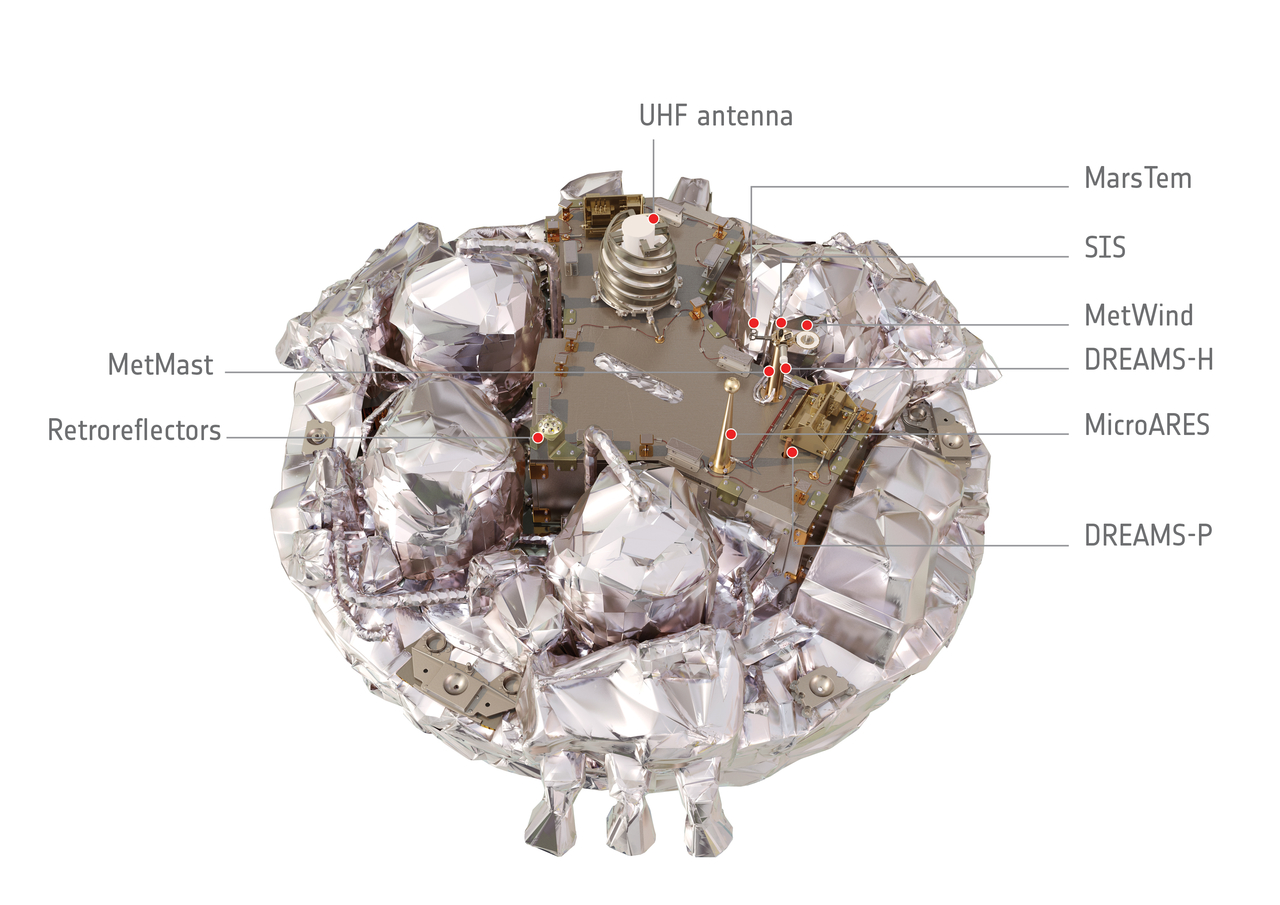

Schiaparelli has a UHF (ultra-high frequency) radio on board that it will use it to transmit signals and data during the entry, descent and landing, as well as talk to ESA and NASA orbiters in the days following its landing. UHF is usually what’s used to transmit television signals on Earth, but it also works great for short-range communication between spacecraft at Mars.

The UHF signal from Schiaparelli’s radio will be transmitted using an antenna on the backshell of the heatshield during entry, and then using the spiral-shaped antenna on the top deck of the lander after it separates from the parachute.

This artist’s impression shows the interior of the Schiaparelli entry, descent and landing demonstrator module. Schiaparelli, part of the ExoMars 2016 mission, was launched together with the Trace Gas Orbiter on 14 March 2016 and will arrive at the Red Planet in October. Credit: ESA/ATG medialab

Schiaparelli will wake up and start transmitting nearly 1.5 hours before the Entry Interface Point – the point at which it reaches the top of Mars’ atmosphere. It will then transmit all the way down through the descent and for around 15 minutes after touchdown. It will then switch to sleep mode to conserve battery power, waking up on a programmed schedule as a series of NASA orbiters pass overhead to receive and relay its data.

Pune listens in

The first we should see on Earth of Schiaparelli’s in-flight, pre-landing wake-up will come via a real-time feed of the signal from the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope (GMRT), located at Pune, India.

The Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope for radio astronomical research at metre wavelengths. GMRT is a very versatile instrument for investigating a variety of radio astrophysical problems ranging from nearby Solar system to the edge of observable Universe. Credit: National Centre for Radio Astrophysics – Tata Institute of Fundamental Research

Our friends from NASA JPL in Pasadena, California, have helped install experimental receiving equipment at the GMRT telescope to help it see not just the wonders of the universe but also track spacecraft like Schiaparelli. The telescope itself is a huge array of radio telescopes near Pune, India, operated by the National Centre for Radio Astrophysics – in all 28 separate 45-m diameter antennas will operate together on landing day to track Schiaparelli’s descent.

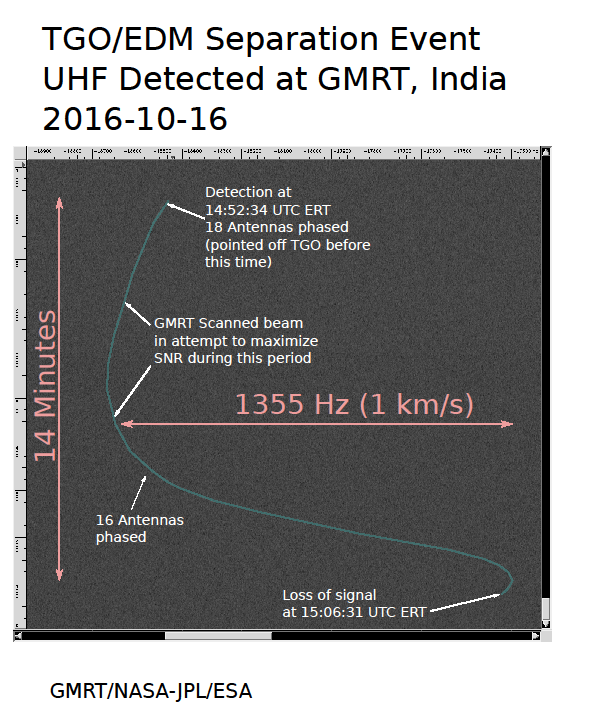

The signal will, for sure be very weak – Schiaparelli was never designed to transmit all the way to Earth. Therefore GMRT tracking of Schiaparelli is very much an experiment – a ‘nice-to-have’ to allow us to watch the descent in real time. In practice testing during Schiaparelli separation from the ExoMars/TGO orbiter, we did see the weak trace of the signal from the lander at GMRT (only 18 then 16 antennas were available) . While this gives us confidence that we will see Schiaparelli landing in real-time (and Pune will employ 28 of the antennas), there are lots of factors during the landing – such as the orientation of the probe – that could cause the signal not to be received at GMRT. Even if we do catch the signal it will be received 9 minutes and 47 seconds after the actual event occurs at Mars – the amount of time the radio signal takes to travel at the speed of light from Mars to Earth on 19 October.

Separation of EDM from TGO as detected at GMRT, Pune, on 16 October 2016. Credit: GMRT/NASA/JPL

MEX

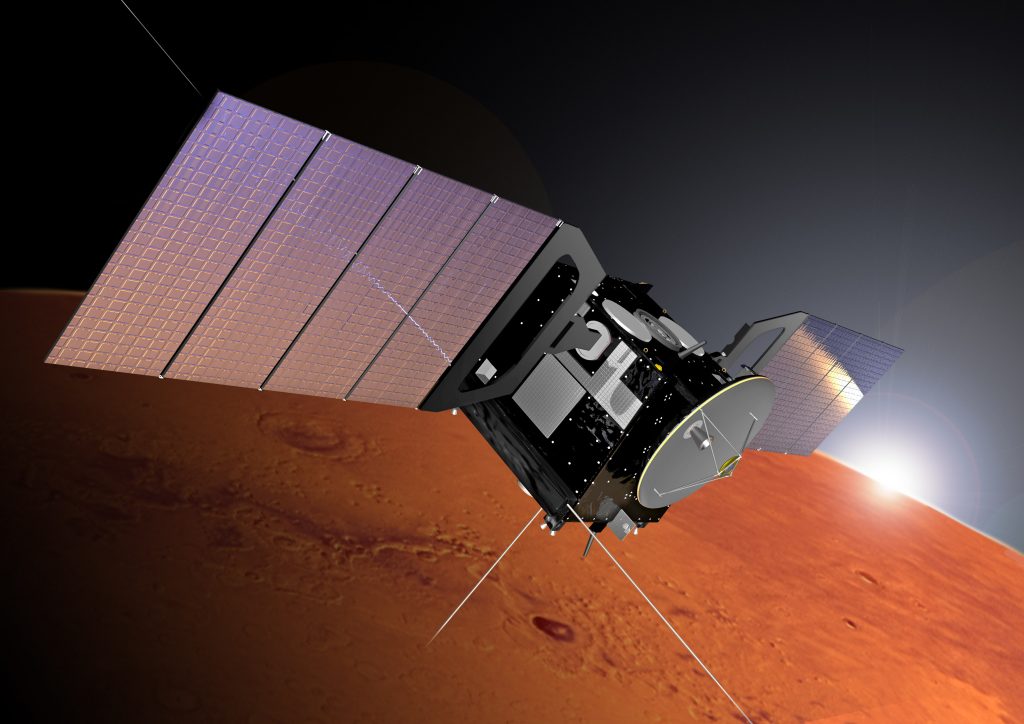

In case we don’t get the signal from GMRT, and to provide more details about what’s happening in any event, we have a much closer listener – the veteran ESA Mars mission, Mars Express.

Mars Express has a UHF radio device on board called Melacom (Mars Express Lander Communication System), which has been used to communicate with a whole bunch of Mars landers – Spirit, Opportunity, Phoenix and Curiosity.

MEX Credit: ESA/Alex Lutkus

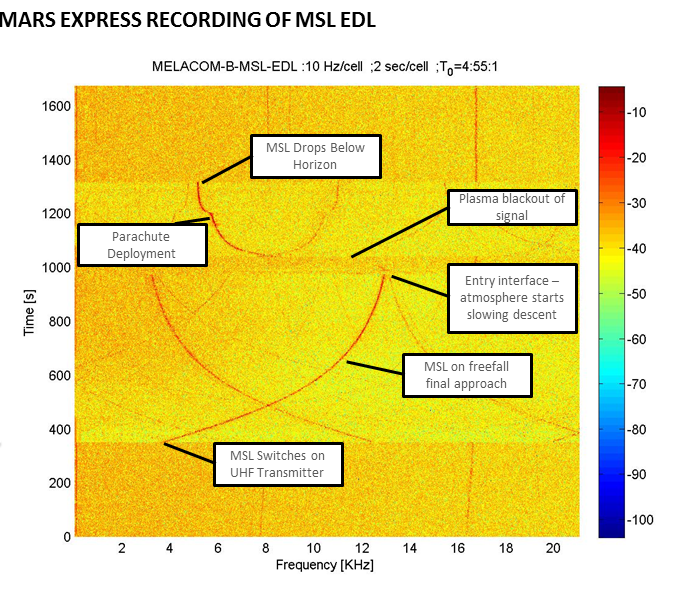

It even has a special ‘open-loop’ recording mode that can track a signal tone from a lander as it arrives at Mars. This has been used successfully to monitor the entry, descent and landing of the NASA landers Phoenix and Curiosity.

Although it cannot decode data in this mode, the Doppler shift that it does receive is very sensitive to changes in the speed of the lander, such as the slowing when it hits the atmosphere, when the parachutes deploy and when it lands. The only downside is that Mars Express has to point the 45-cm Melacom antennas at Mars to record the signal, so can’t relay the received signal in real time to Earth. Instead, as soon as Schiaparelli is on the ground, Mars Express will turn back to Earth and replay the recording, which will be received by ESA’s Cebreros ground station and transferred to ESOC, our mission control centre in Darmstadt, Germany, where it will be processed and made available to the teams here around 1.5 hours after Schiaparelli touchdown.

More ears in orbit

We don’t stop there though – even after the GMRT tracking and the Mars Express recording – we have yet another chance to communicate with Schiaparelli in case neither of those hear anything.

Here, we’ll get a little more help from our friends at NASA/JPL, when their Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) flies over the Schiaparelli landing site just under two hours after landing. At this time, Schiaparelli should wake up ready to talk to MRO, which will hail the lander using its Electra UHF radio and establish an 8-minute-long, two-way communication link to get all the latest status information and data from the lander. This data will then be sent to Earth around 1.5 hours later and will give us the final word that Schiaparelli is safely on the ground and functioning as the newest robotic resident of Mars.

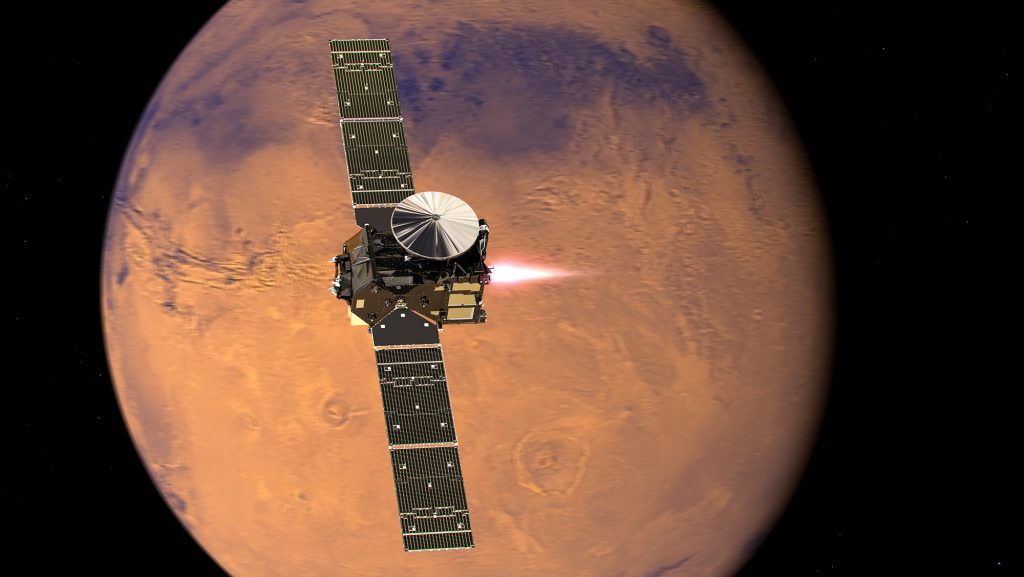

Finally, though there is one more listener around Mars – Schiaparelli’s mothership, the Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO).

Trace Gas Orbiter entering orbit around Mars on 19 October 2016 Credit: ESA/ATG medialab

TGO is also fitted with an Electra UHF radio and will be listening in on the Schiaparelli descent, while simultaneously performing its Mars Orbit Insertion burn. What Electra can do differently than GMRT or Mars Express is record actual data that are being streamed to it on the Schiaparelli signal, giving precise details and measurements of the descent progress all the way down.

This will be invaluable for engineers in order to piece together the exact performance of the Schiaparelli journey to the surface. However, as TGO will be a little busy at the time with its own orbit entry, this data won’t be down linked to Earth until sometime later and then processed in the early hours of the morning after landing, on 20 October.

From the top down

So, to summarise (Well done for staying with us until this point!), monitoring Schiaparelli’s landing on Mars will be a complicated, multi-step process during which we’ll rely very much on help from our friends around the world – an important consideration given that landing on another planet can be very risky.

Most importantly, no one single part of the listening support matrix not working is an indication that all is lost – only with all of them will we have the complete picture. In summary, here are the steps:

- Real-time: Experimental tracking by the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope in Pune, India. We hope to catch the very faint signal all the way from Mars on Earth

- 1.5 hours after landing: Recording of the Schiaparelli signal from Mars Express will be available, giving a detailed close-up view of the event

- Two hours after landing: Results of the first nominal communication pass over Schiaparelli after landing that was performed by NASA/JPL’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter will be available at ESOC

- 20 October: Detailed data recording of the telemetry from descent will be available from TGO

Thank you to all who are supporting our teams and the TGO and Schiaparelli missions by helping us get the most up-to-date and accurate information we can about the momentous landing of Schiaparelli!

Follow along with us tomorrow on twitter.com/esaoperations.

Discussion: 8 comments

“Two hours after landing: Results of the first nominal communication pass … performed by … Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter will be available at ESOC”

Earlier in the article it is said that the MRO data will get down around 3.5 hours after EDM landing?!

Saludos !

pues no deja de ser un proyecto interesante a pesar de lo complicado, esperamos que se exitoso !

Thank you for the great explanation. It is always much more complex than it seems. Keeping fingers crossed!

Estão precisando de ajuda

Merci pour les explications , vivement la conquête de mars

News? Is the lander comunicating?

Thanks Thomas, for again a very detailed description of a vital part of the mission.

So the Pune station is receiving the UHF signal so faintly, it cannot decode data, MEX is receiving the same signal but cannot decode because recording in open loop, and TGO is also receiving the same signal and can decode it. Correct?

Why is TGO able to decode and MEX not? What’s the difference?

Is Schiaparelli using the same approach as MSL Curiousity during EDL (Entry, Descent & Landing): 256 different tones that could be transmitted, indicating the various phases of EDL?

Sorry for being just curious

Please, could we get a detailed nominal EDL timeline?