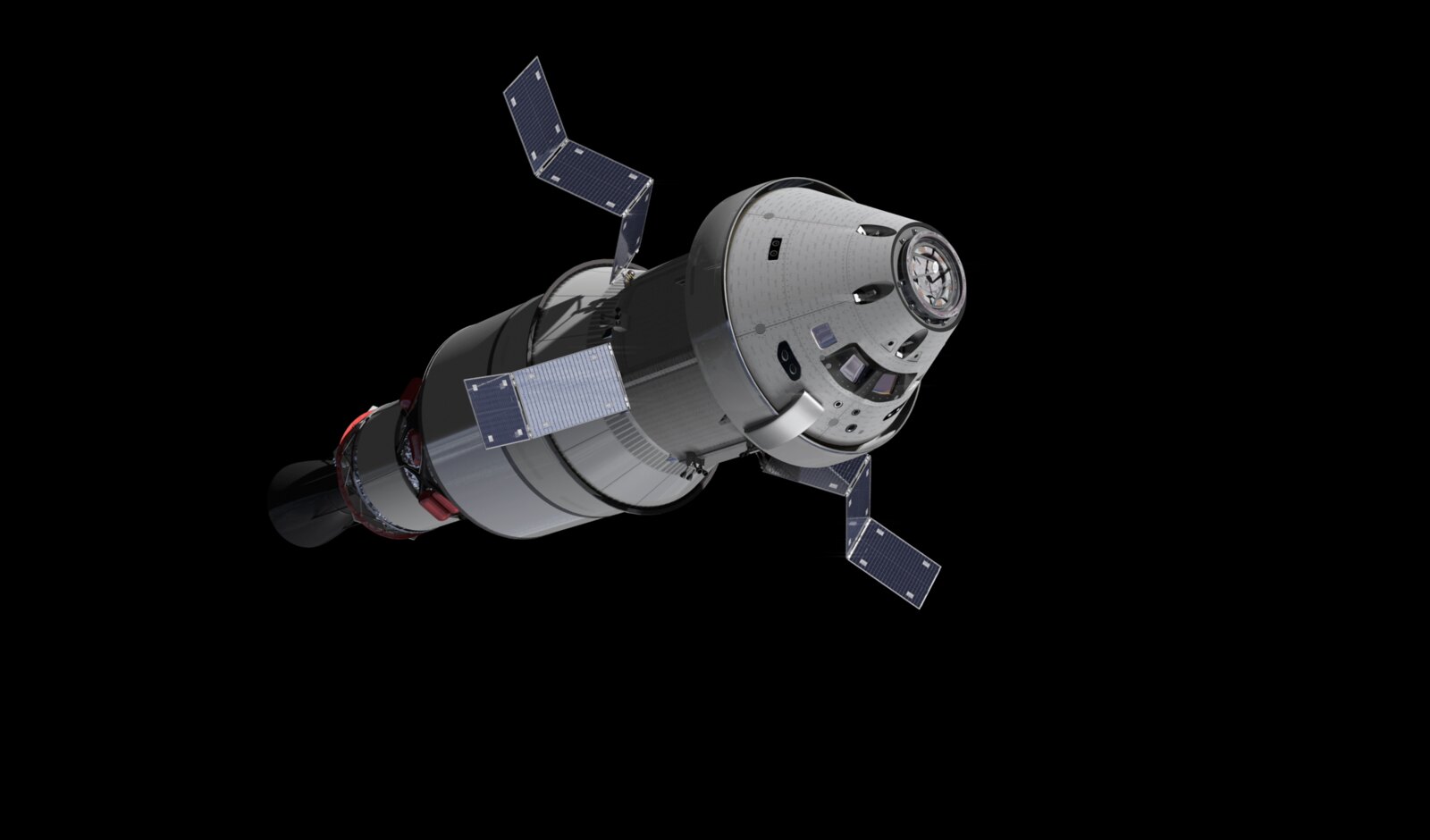

Teams at NASA’s mission control in Houston, USA, conducted spacecraft system checks preparing for Orion’s splashdown on 11 December, as the recovery teams prepared on Earth around the landing area off the Baja Coast near Guadalupe Island.

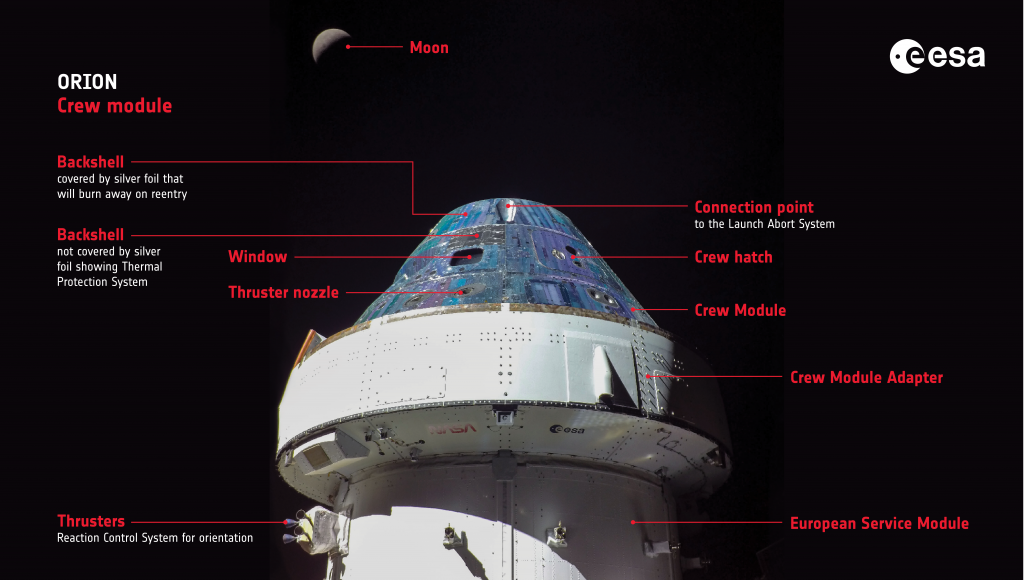

Flight controllers activated the crew module reaction control system heaters to warm the thrusters up for a hot-fire test of each thruster. The five pulses for each thruster lasted 75 ms each, and were conducted in opposing pairs to neutralise as much as possible any movement to the spacecraft. The crew module propulsion system is made of 12 monopropellant MR-104G engines. These engines are a variant of MR-104 thrusters, which have been used in other NASA spacecraft, including the interplanetary Voyagers 1 and 2. The European Service Module thrusters use bipropellant thrusters that mix fuel and oxidiser to ignite.

Approximately 5488 kg of propellant have been used, which is 110 kg less than estimated before launch.

Radiation again

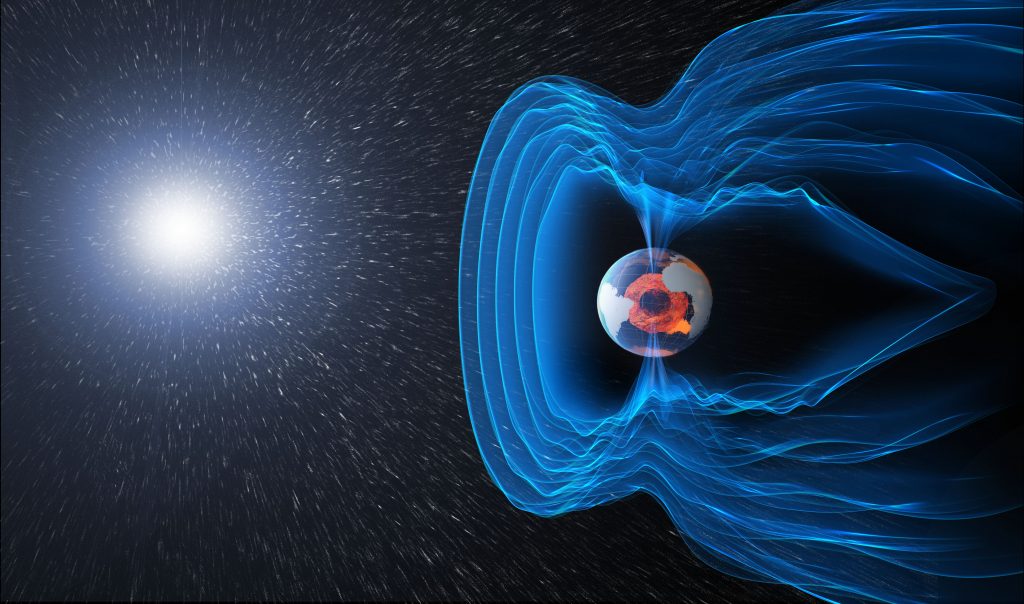

As it travels back to Earth, Orion will pass through a period of intense radiation as it passes through the Van Allen Belts that contain space radiation trapped around Earth by our magnetosphere. Outside the protection of Earth’s magnetic field, radiation in deep space includes energetic particles produced by the Sun during solar flares as well as particles from cosmic rays that come from outside the galaxy.

Orion was designed from the start to ensure reliability of essential spacecraft systems during potential radiation events and can become a makeshift storm shelter when crew members use shielding materials to form a barrier against solar energetic particles.

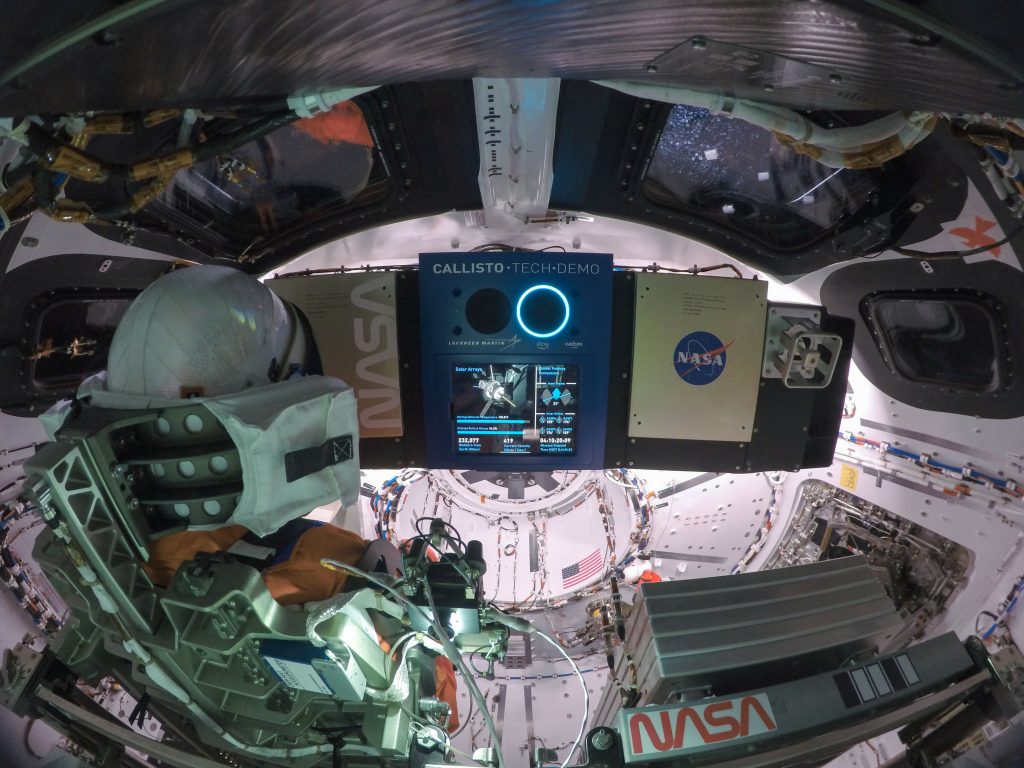

For the uncrewed Artemis I mission, Orion is carrying several instruments and experiments to better understand the environment future astronauts will experience and provide valuable information for engineers to develop more protective measures. There are active sensors connected to power that can send readings to Earth during the flight, as well as passive detectors that require no power source to collect radiation dose information that will be analysed after the flight.

In addition to the radiation phantoms Helga and Zohar, Commander Moonikin Campos has two radiation sensors, as well as a sensor under the headrest and another behind the seat to record acceleration and vibration throughout the Artemis I mission. The seat is set in a laid-back position with the feet up, which will help maintain blood flow to the head for astronauts on future Artemis missions during launch and return to Earth. The position also reduces the chance of injury by allowing the head and feet to be held securely and by distributing forces across the entire torso during high acceleration and deceleration periods, such as splashdown.

Artemis astronauts are expected to experience two-and-a-half times the force of gravity during ascent and four times the force of gravity at two different points during reentry. Engineers will compare Artemis I flight data with previous ground-based vibration tests with the same manikin, and human subjects, to correlate performance prior to Artemis II.

In addition to the sensors on the seat, Campos is wearing a first-generation Orion Crew Survival System pressure suit – a spacesuit astronauts will wear during launch, entry, and other dynamic phases of their missions. Even though it’s primarily designed for launch and reentry, the Orion suit can keep astronauts alive if Orion were to lose cabin pressure during the journey out to the Moon, while adjusting orbits in Gateway, or on the way back home. Astronauts could survive inside the suit for up to six days as they make their way back to Earth. The outer cover layer is orange to make crew members easily visible in the ocean should they ever need to exit Orion without the assistance of recovery personnel, and the suit is equipped with several features for fit and function.

Shortly before 21:30 CET (20:30 GMT) on 9 December, Orion was traveling over 276 00 km from Earth and 344 720 miles from the Moon, cruising at 3380 km/h.

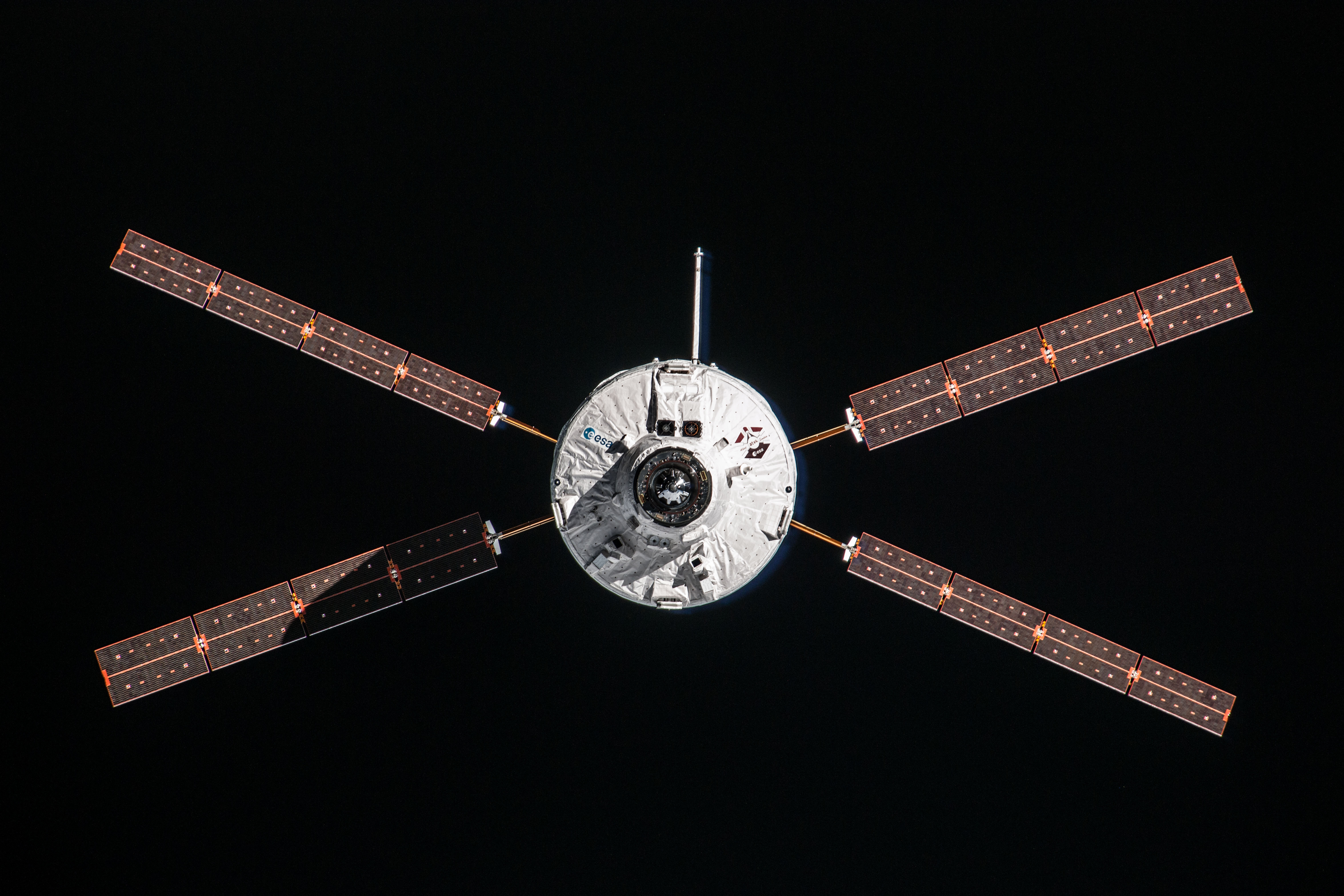

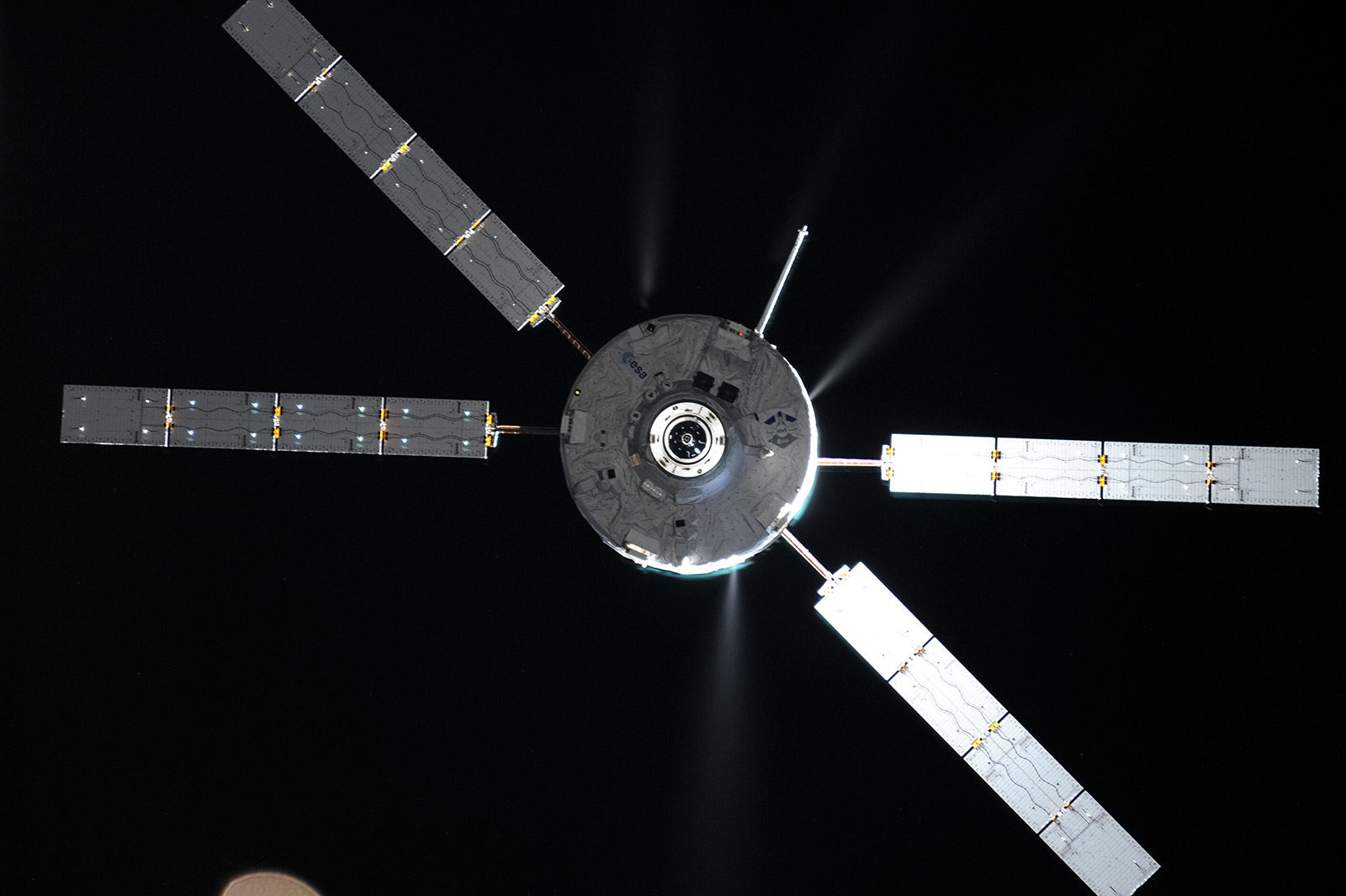

Automated Transfer Vehicle page

Automated Transfer Vehicle page ATV blog archive

ATV blog archive

Discussion: no comments