Today marks one year since NASA’s Artemis I launch. The mission surpassed its main objective: testing every detail of the mission scenario and Orion spacecraft before the crewed Artemis II mission. But no mission is perfect.

Here is the behind-the-scenes story of how an anomaly in the power conditioning and distribution unit, or PCDU, gave our engineers a temporary fright and what they did about it. We hear the story from Antonio Preden, head of the engineering team for the European Service Module at ESA.

Behind the P-sCene-DU

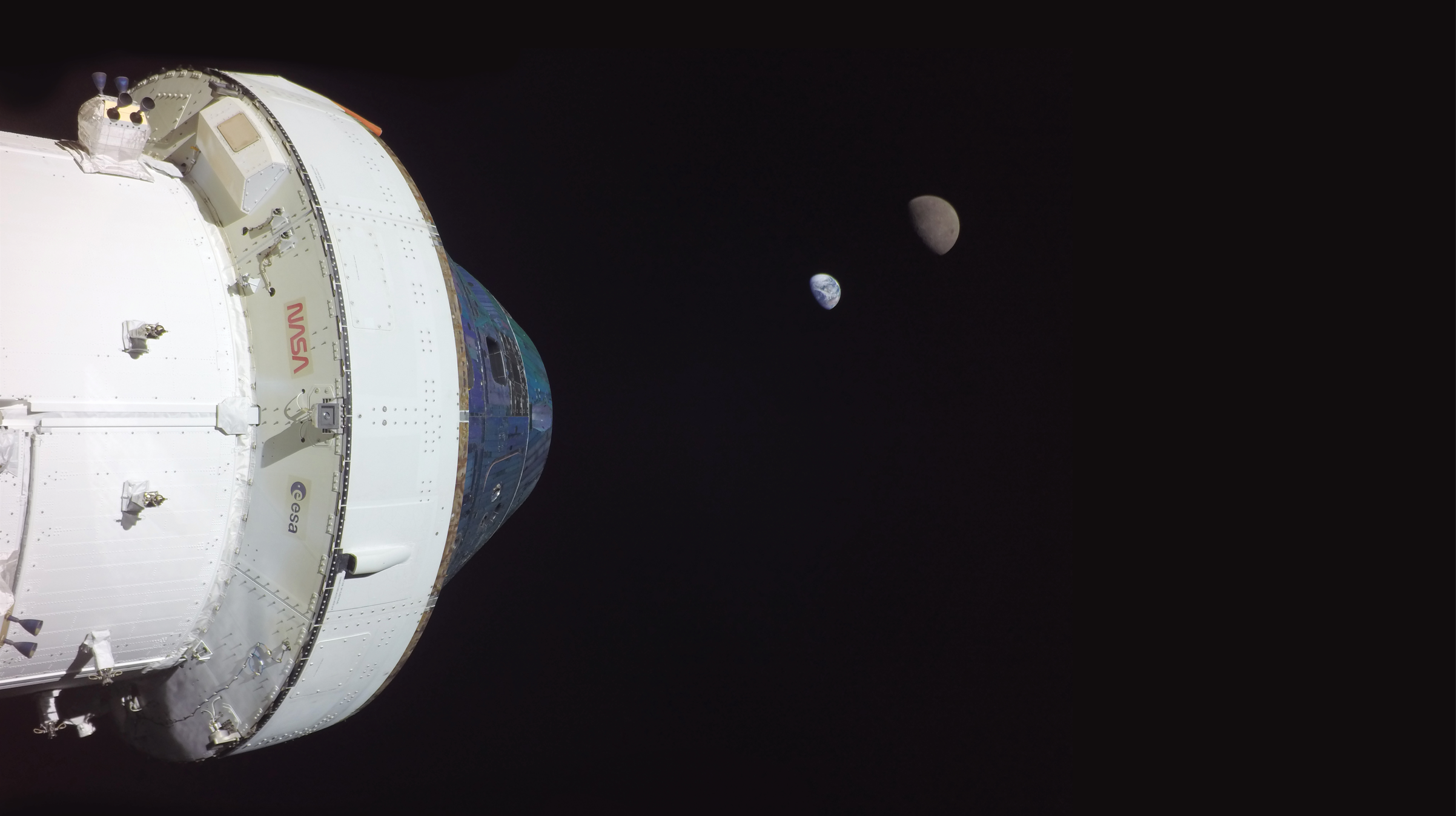

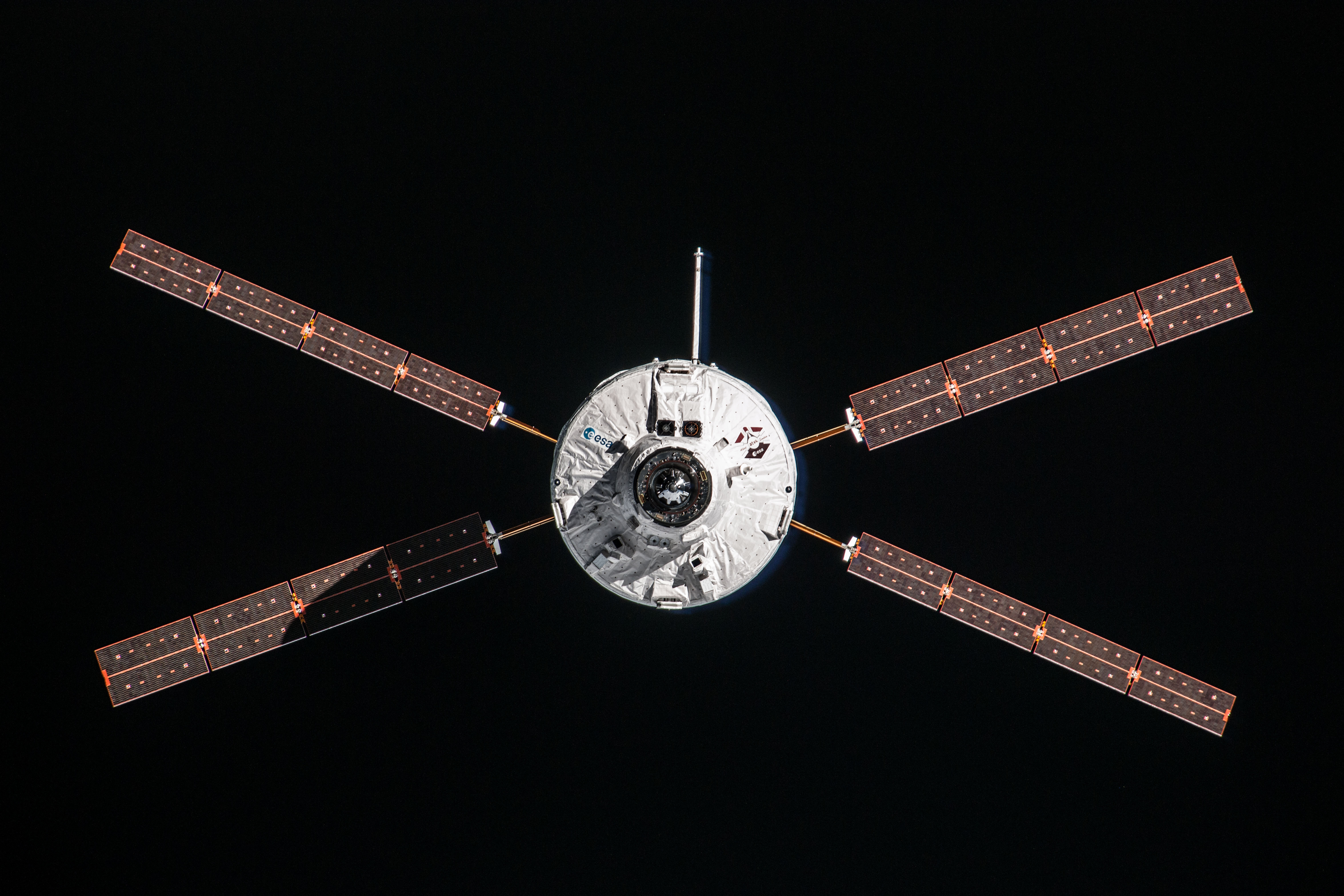

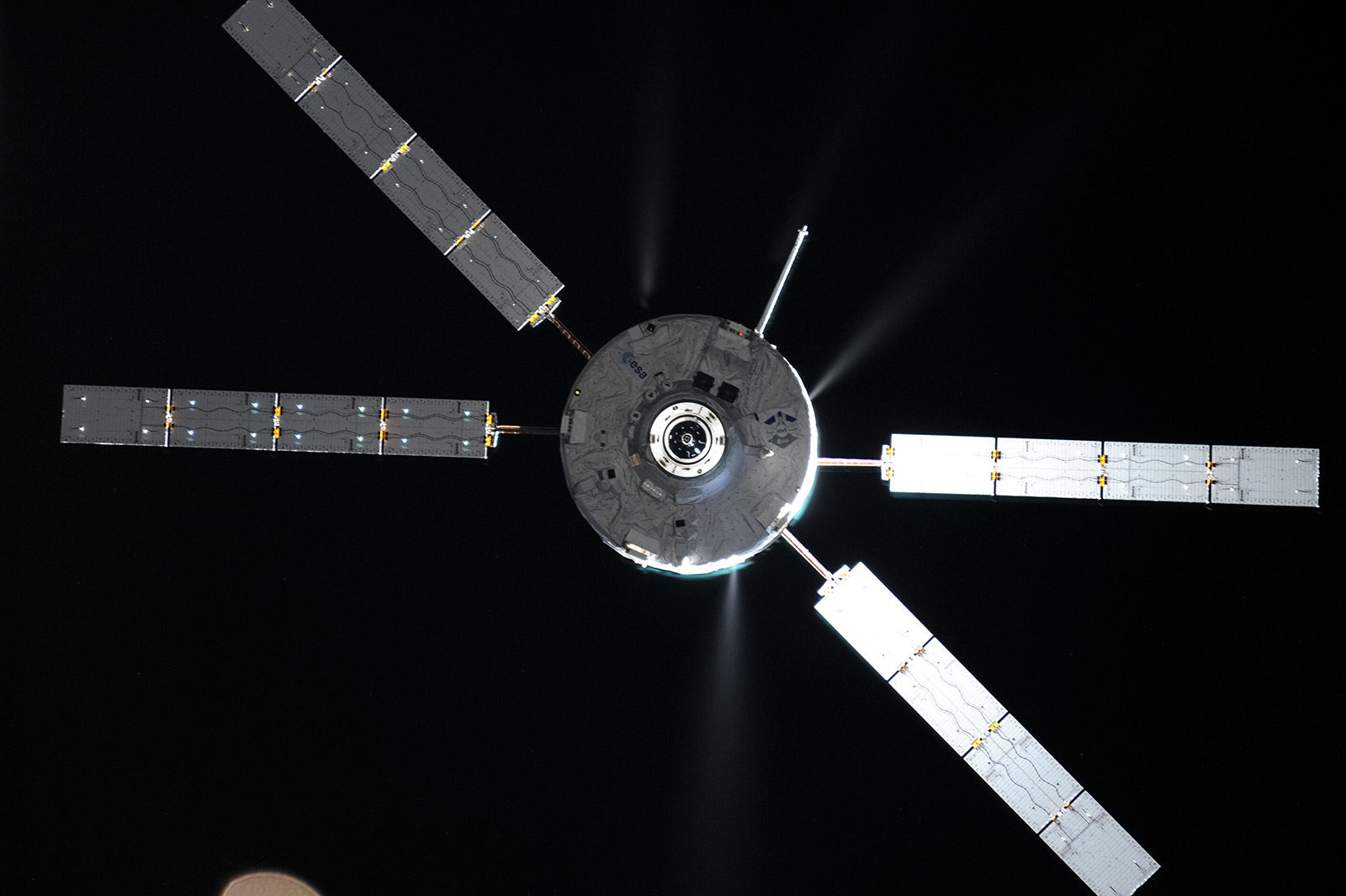

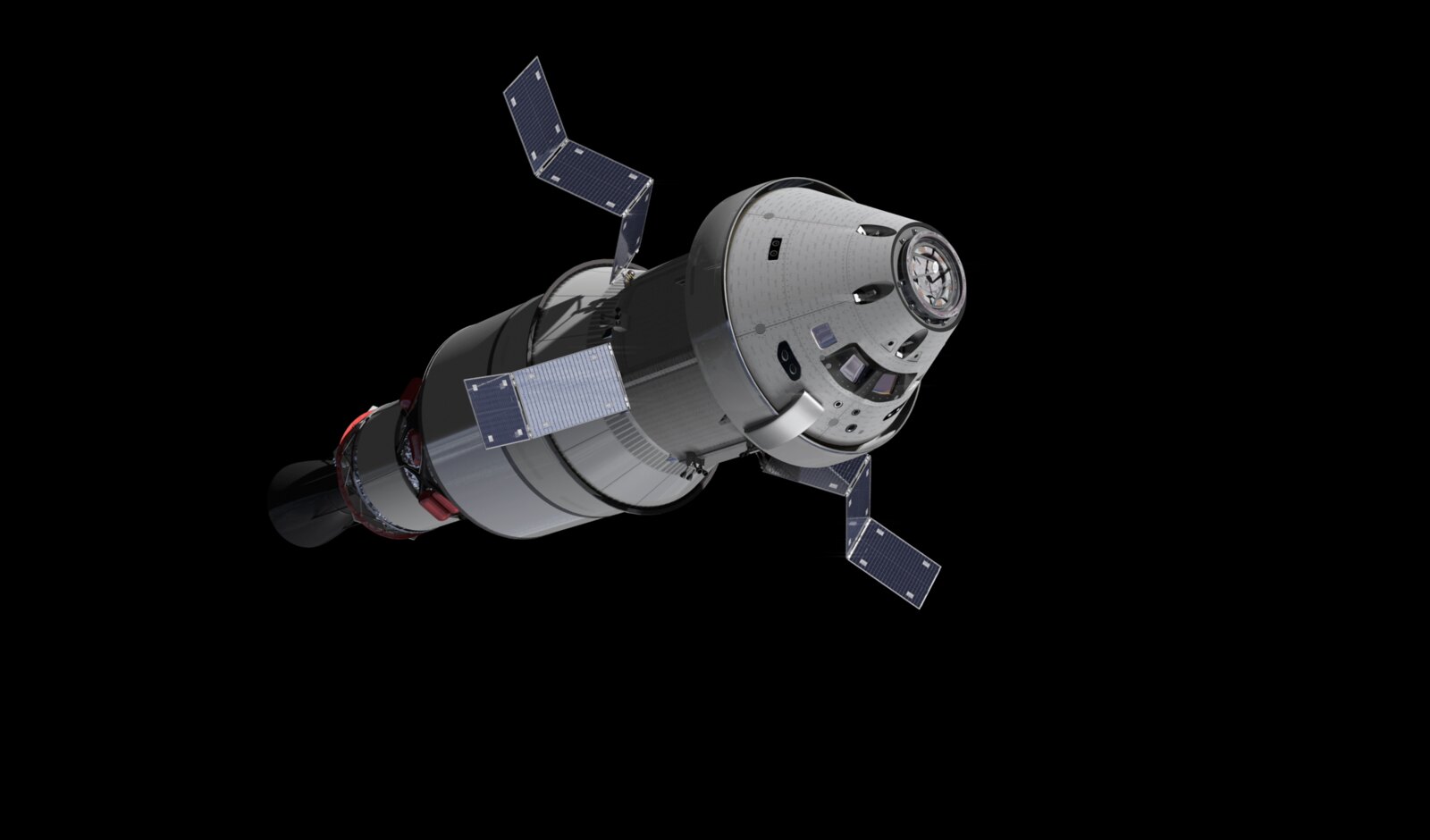

One year ago today, NASA’s mega Moon rocket SLS launched the Orion vehicle into space, where it was propelled to the Moon and back, over 2.25 million km, by ESA’s European Service Module. The Artemis I mission did everything it was supposed to and more. The European Service Module in particular went literally above and beyond: executing its challenging manoeuvres to a tee and generating so much extra power with its solar arrays that it had time to use them as selfie sticks to take great mission pictures.

However, engineers are not the type to rest on their laurels. Throughout the mission, there were signs of an anomaly in the behaviour of the power unit of the European Service Module. Although the anomaly was quickly found to not be mission-critical, Antonio Preden and the team have been hard at work trying to find out why this happened.

View of the Orion capsule as it reached a maximum distance from Earth, surpassing the record for distance traveled by a spacecraft designed to carry humans set during Apollo 13. Credits: NASA

Could you tell us what happened?

There was an anomaly with one of the power conditioning units; these units regulate the power received from the solar array wings and convert them into an even supply, before distributing electricity to where it is needed. On flight day 19, four components that limit this distribution were switched open without us commanding them to. We quickly got to work confirming the system was healthy and were able to solve the issue. There was no interruption of power to any critical systems, and no adverse effects, but we knew this was something we had to investigate.

When did you first realise something strange might be happening?

Almost from the start of the mission. A few hours after launch, we already experienced a glitch. We thought it must have been some spurious effect, but when it happened again the day after, we knew it couldn’t be random. We started investigating whether it was an issue on the ground, but quickly understood it must be an issue on board the Orion vehicle in space. We could not explain what was happening so this was a difficult situation for us.

How did you investigate the anomaly?

We had some busy days! We thought about all the possible causes of the anomaly. After ruling out some options, we began to suspect some electrical interference was reaching the power unit box and generating the trigger that opened these switches. From then, we started testing our hypothesis, both in-flight and on the ground.

Who was involved in the investigations on the ground?

We activated support from engineers in aerospace companies all over Europe: from Leonardo in Italy, where the power unit was designed, and from Airbus, the prime contractors for the European Service Module.

At the Airbus electrical test facility of Les Mureaux in France, engineers worked on this idea of electrical noise being the culprit. They simulated a very high level of noise into the power unit box and managed to reproduce something very similar to the anomaly we had seen during the flight. From that moment, we thought we were on a good path to understanding what happened but still had a lot of work to do.

So the work wasn’t over when the Artemis I flight ended?

Definitely not! One thing to realise is that once the flight ends, the work doesn’t end; it’s just the start of post-flight analysis. And Artemis I is a mission that was pushed beyond its planned flight, so we have a lot of data to analyse. So, our investigations continued for several months. We continued trying to replicate the anomaly, but we never got as close as what was observed in flight, even by simulating higher and higher levels of electrical noise, until it just wasn’t realistic anymore.

Did you start thinking maybe you had the wrong hypothesis?

Yes, we really started scratching our heads. Although the Artemis I flight was over, the fact we couldn’t understand exactly what had happened meant we had to figure it out before the next mission: before you fly a spacecraft, especially one with crew, you have to be able to explain every phenomena. After months of working on the electrical interference hypothesis, we had to go back to the drawing board. That is the engineer’s way.

Experts from industry started thinking about everything and anything that could have happened to trigger this switch. And they started thinking, what if a glitch in a completely different section of the power unit could have propagated to the zone with the switches that opened without command? And if so, what could have caused this glitch in a different location?

Was that your breakthrough moment?

Exactly. We identified a small electric component that is sensitive to radiation in a different section of the power unit to the one we had been investigating. Radiation in space is always a critical issue; on the ground, we are protected by Earth’s magnetic field, but in space the charged particles can wreak havoc on electronics. And we realised that radiation in space was causing a glitch of micro- or even nano-seconds, generating a sequence of events which propagated throughout the power unit and led to opening the switch.

Finally, we had understood the mechanism, We tested to confirm this was the cause, and that gave us a full understanding of what had happened. It also confirmed to us that the worst that could happen due to the glitch was what we saw in Artemis I, which had no negative impact, so that reassured us.

What’s next?

Now, we are looking to the future and shifting our focus. We spent much effort analysing what happened during Artemis I, not just the power unit anomaly but everything else. Today, we are looking to future Artemis missions, to see how we can use everything we have learnt to prepare for our return to the Moon. Something that will surely stay with us is how teams all over Europe mobilised to work together and find a solution to this problem.

Luca Fossati, avionics system engineer for the European Service Module at ESA, on console during the Artemis I mission. Credits: ESA–A. Conigli

Automated Transfer Vehicle page

Automated Transfer Vehicle page ATV blog archive

ATV blog archive

Discussion: one comment

Thank you for the nice post.