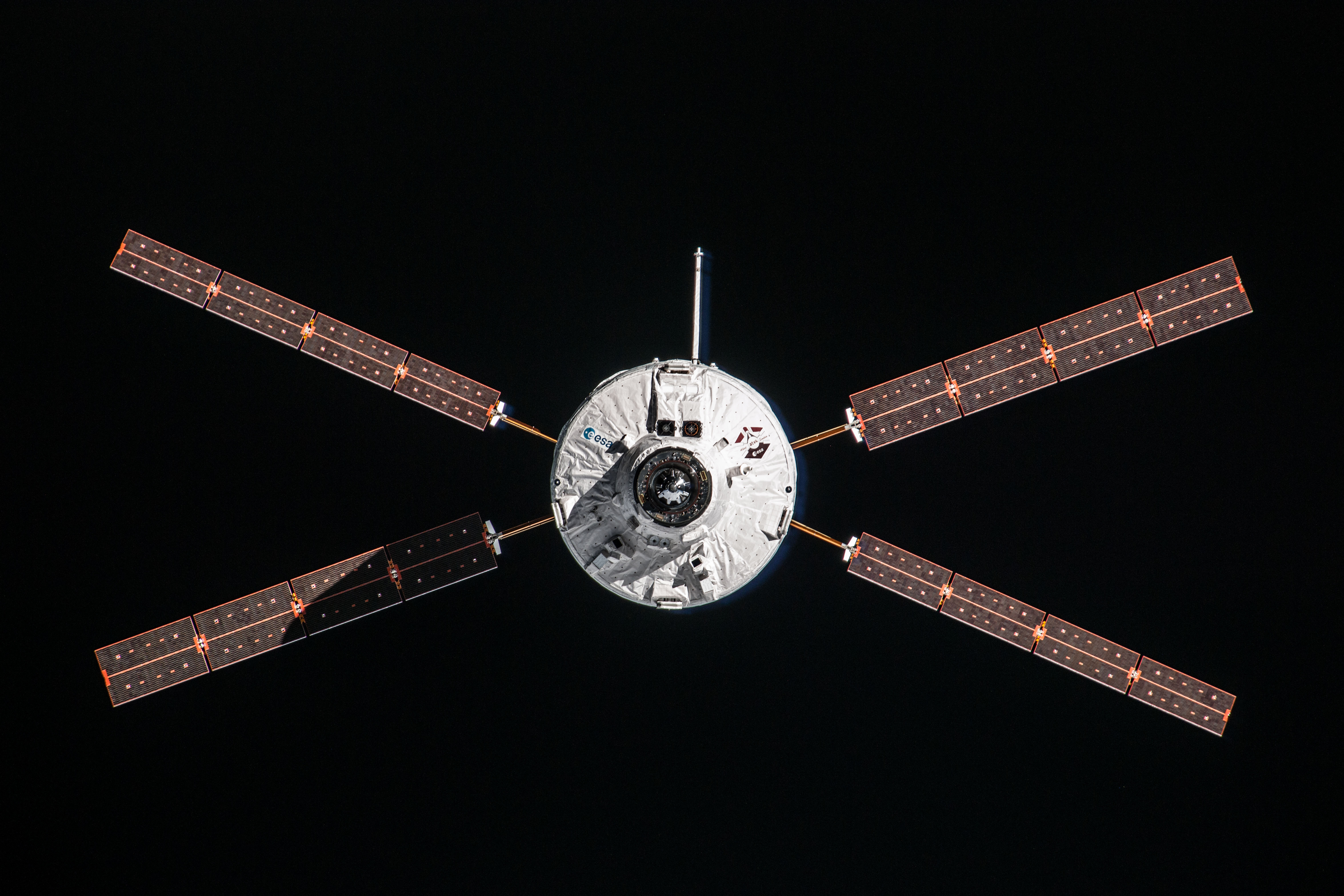

ESA astronaut Alexander Gerst is one of the last astronauts to train at the European Astronaut Centre on ATV. Alex is preparing for his mission to the International Space Station in May and will be part of the crew to monitor ATV-5 docking, the last of the series:

A looming virtual ATV approaches the Zvezda mockup. Note the updated mission logo – ATV5

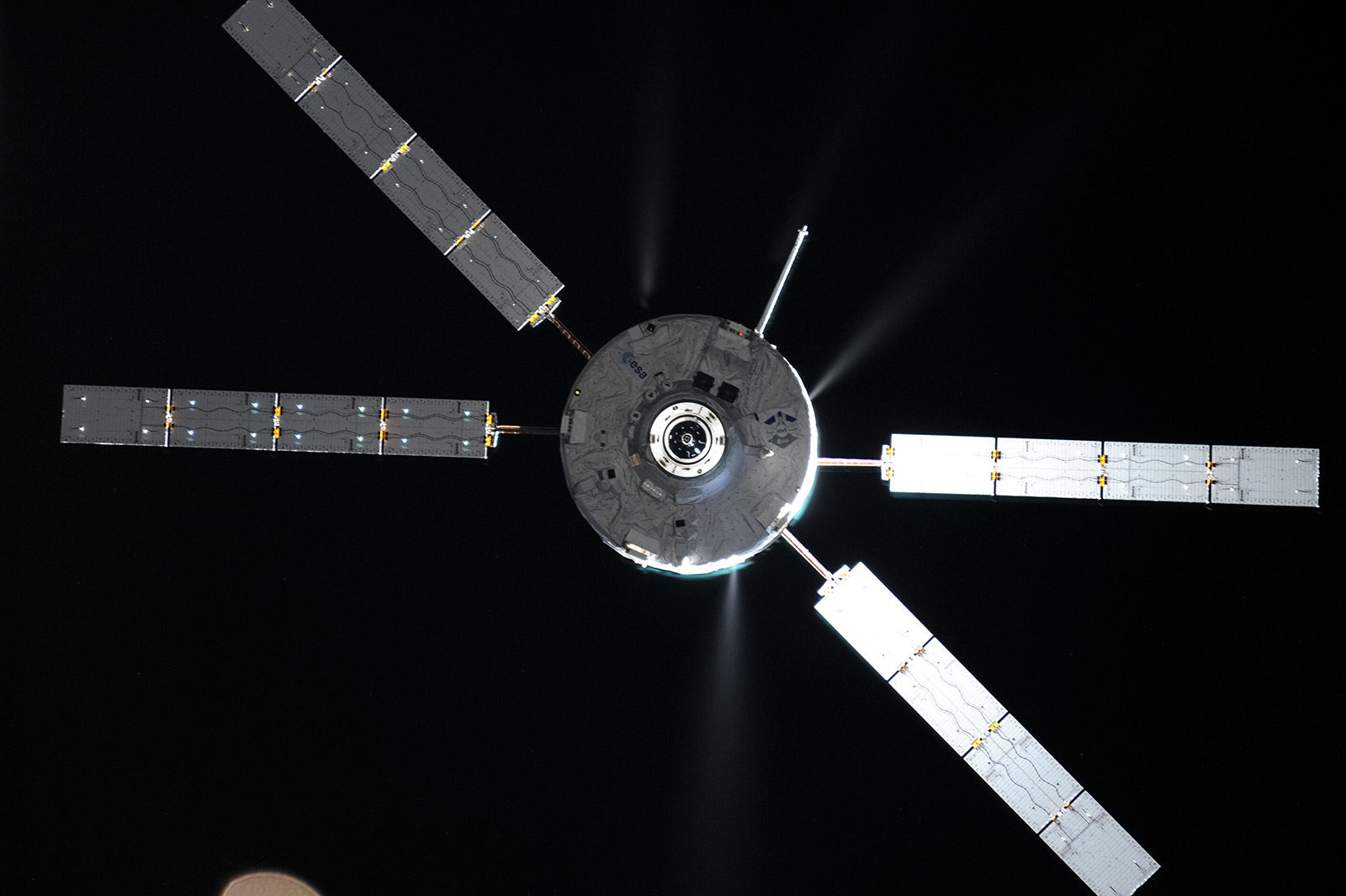

Escape or Abort? ATV has drifted off its acceptable approach corridor and a spacecraft the size of a double-decker bus is heading straight towards us. ESA astronaut Alexander Gerst has unscrewed the protections covering both buttons on the ATV control panel. Protocol dictates that drifting off course at this distance demands a quick bash of the escape button – sending ATV back a safe distance. A last look at the relative speed of the incoming spacecraft shows that it is above 0.15 m/s, or 1 cm/s too fast. Alex doesn’t hesitate and hits the Abort button. At these speeds it is better to not take any chances.

The simulation is over and the ATV instructors confirm he has passed the test. Alex is following his second intense week of ATV rendezvous-and-docking simulations at the European Astronaut Centre in Cologne, Germany. Three qualified instructors gave an hour lecture followed by a simulation. ATV training follows three phases , broadly speaking, theory, simulations and refresher courses both on Earth and on the International Space Station.

The simulation is over and the ATV instructors confirm he has passed the test. Alex is following his second intense week of ATV rendezvous-and-docking simulations at the European Astronaut Centre in Cologne, Germany. Three qualified instructors gave an hour lecture followed by a simulation. ATV training follows three phases , broadly speaking, theory, simulations and refresher courses both on Earth and on the International Space Station.

Trainer Michael Markus during the classroom theory session likens ATV docking to flying a carrier jet over the Atlantic ocean: “A pilot spends most of the time repeatedly checking instruments: ‘altitude: OK, speed: OK, position: OK, altitude: OK, speed: OK, position: OK, altitude: anomaly’. Only in the unlikely event of something going wrong must pilots and astronauts react, but they must be prepared and react immediately.”

“Because failure is so unlikely humans run the risk of being complacent” continues Michael “that is why we simulate failures repeatedly in spaceflight training.”

Lionel and Alex

Moving on from the theory classroom, Lionel Ferra runs us through the ATV control panel and monitors. Everything is based on double or even triple fault tolerance. The Russian control panel might look clunky but it is specifically designed for safety. The three red lights above all switches represent three distinct channels used to send commands. Two can fall out and everything will still work fine.

ATV control panel at EAC

Important commands such as Escape or Abort are protected by screw-covers. Alexander explains : “The covers are there as a psychological barrier rather than a physical barrier, they are meant to make me think: do I really want to do this?”

Lionel goes over the tools of ATV docking: a ‘cheat sheet’ listing potential malfunctions and how the crew should react throughout ATV approach, a ruler to visually check distance on the video monitor and a computer laptop that displays information on ATV.

“Today all the systems are mock-ups, except the laptop which is exactly the same as the one used on the Station and our astronaut Alex of course” he jokes.

Alex using a ruler to check distance during simulation

“ATV docking is an amazing mix of high-tech and low-tech” explains Lionel. “Lasers on the ATV give extremely accurate distance readings but these readings are double-checked by astronauts using a simple ruler placed over the monitoring screen.”

During an ATV docking, virtual cones extending from the docking port are considered safety corridors. If ATV drifts of course – outside of the projected cone – the astronauts on the International Space Station must step in. The corridor does not extend from the centre of the docking port as you might expect, but from the outside camera that films the docking. A target on ATV is placed slightly off-centre to align with the camera, not the docking port. Thanks to this visual target, Alex is able to directly read ATV’s orientation and position in three-dimensional space.

ATV-CC, Tsup, and Houston Mission Control in one: Oleg

It is time for the simulation to begin. Alex and Lionel move to the life-size mockup of the Russian Zvezda module at the European Astronaut Centre. Phones must be left at the entrance, they interfere with the communication signals. Trainer Oleg Polovnikov stays behind to simulate Moscow Mission Control ‘Tsup’, Houston Mission Control and the ATV Control Centre, a demanding job for a single person!

Alex during ATV docking simulation

Set up in front of the mock ATV docking, Lionel asks Oleg to load a simulation: “…and make it a difficult one”. A computer generated ATV Georges Lemaître appears on the monitor. Immediately Alex and Lionel start communicating parameters back to ‘Mission control’ in fluent Russian: “Системы в норме” and “Мишень в норме” meaning “all systems are nominal” and “target is nominal”. Shortly ATV starts to deviate from its planned trajectory and Alex monitors closely, pressing the right buttons at all the right times, choosing for Escape based on the cheat-sheet that he hardly needs consulting.

After the simulation has ended the so-called off-nominal procedures are run through. What could Alex have done if the Abort button did not work? The sheet offers but one advice: push the button again. Alex smiles and explains there is not much that can be done beyond that point anyway “I had already pressed the button twice in any case, it is an astronaut thing: best to be sure.”

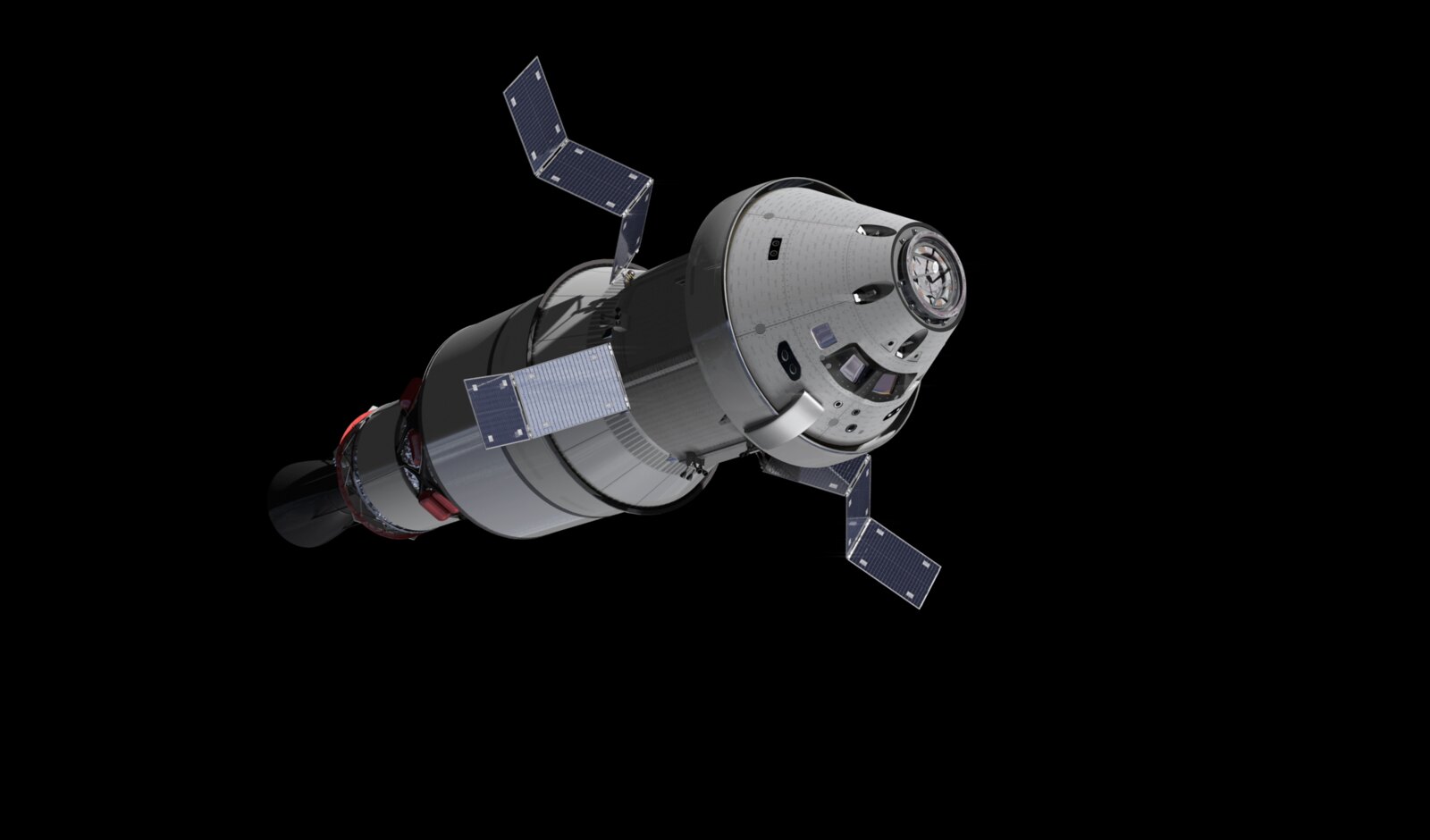

Automated Transfer Vehicle page

Automated Transfer Vehicle page ATV blog archive

ATV blog archive

Discussion: one comment

Thanks very good post