- ESA’s Mars Express team is planning a series of five communication tests with the Chinese Zhurong Mars rover in November.

- The Mars Express spacecraft can ‘hear’ the rover, but the rover cannot ‘hear’ Mars Express.

- Zhurong will transmit data ‘blind’ as part of a technique designed over a decade ago but not tested in orbit until now.

- ESA will pass any received data on to the Zhurong team for analysis.

What is Zhurong?

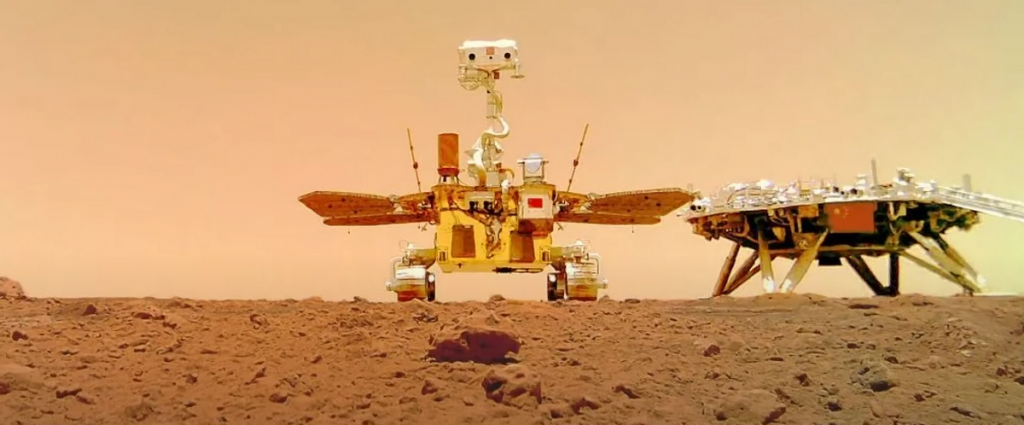

On 14 May 2021, the China National Space Administration (CNSA) landed its first rover, Zhurong, on the surface of Mars. Since then, it has explored the region around its landing site in Utopia Planitia and collected important data on the Martian climate, surface and interior. But to get these data back to Earth, the rover needs a helping hand from orbit.

Relaying science data from Mars

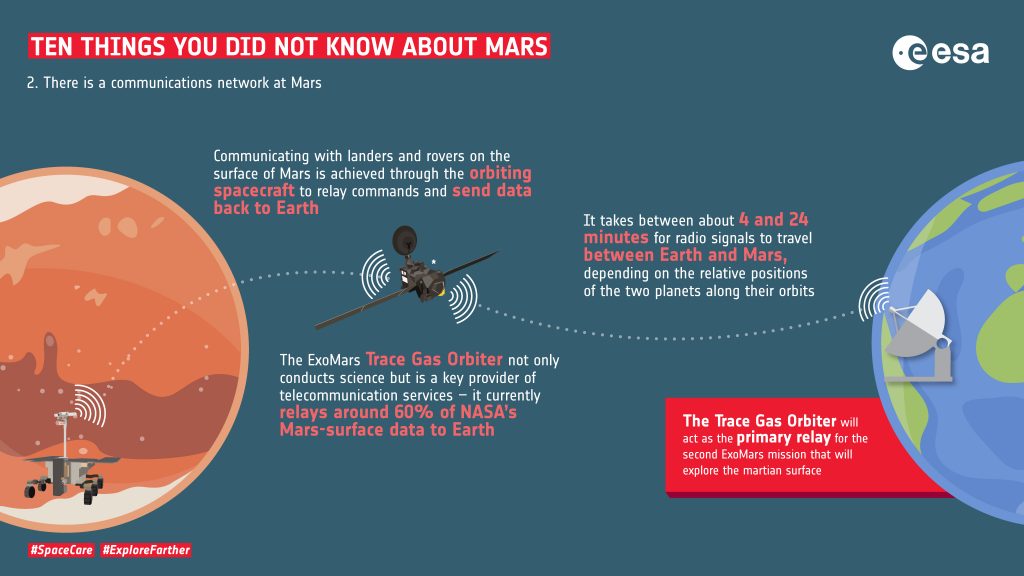

Landers and rovers like Zhurong need to get the large volumes of science data they collect back to Earth for analysis. But the equipment they would need to transmit these data directly to Earth from the Martian surface would take up lots of valuable space and mass – space that is better used to pack as many science instruments on the rover as possible.

To solve this issue, landers and rovers are instead equipped with small, short-range radios. Similar radios are carried by the spacecraft orbiting the Red Planet, such as ESA’s Mars Express and the ESA-Roscosmos ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter.

This allows a lander or rover to send its data up to an orbiter, which then use its larger, more powerful transmitter to forward the data across the vast interplanetary distance to Earth. The data are received on Earth by the large antennas at deep space ground stations like those in ESA’s Estrack network.

This data relay approach has become the standard for operating rovers and landers on Mars.

Since landing in May, Zhurong has relayed data back to its team using the Chinese Tianwen-1 orbiter with which it arrived. However, it is often useful to explore alternative ways to get your data back to Earth. One common solution is to use the Mars orbiters of other space agencies to provide data relay support.

In November, ESA’s Mars Express will perform a series of five tests in which it will attempt to receive data from Zhurong and relay it to ESA’s ESOC Operations Centre in Darmstadt.

This is also a chance for the Mars Express team to test a backup method for communicating with Mars landers, designed over a decade ago but never before tested live in orbit.

A not-so-new approach makes its debut

Normally, when an orbiter flies over a rover, it sends down a hello known as a ‘hail signal’ to initiate communications. The rover then sends back a response to let the orbiter know it received the hail and that the exchange of data or commands can begin.

However, due to an incompatibility between the two radio systems, the Zhurong rover cannot receive the frequencies used by Mars Express, so it cannot respond to a traditional hail signal from the spacecraft. Fortunately though, it can transmit a frequency compatible with Mars Express.

To account for situations like this in which the typical hail and response is impossible, the Melacom radio system on Mars Express was designed to be able to listen for a specific signal being transmitted ‘blind’ by a rover on the surface and examine it to see if it contains any data.

When Mars Express flies over Zhurong’s landing site in Utopia Planitia, it will switch on its radio and listen. If it detects the magic signal, the radio will lock on to it and begin recording any data. At the end of the communication window, the spacecraft will turn to face Earth and relay these data across space the same way it does for other scientific Mars missions. When the data arrive at ESOC, they will be forwarded on to the Zhurong team for processing and analysis.

While this ‘blind’ technique has been available for over 10 years, and has been thoroughly tested on Earth, it has not been used in orbit around another planet. The five communication test windows between Mars Express and Zhurong – each lasting approximately 10 minutes – are a great opportunity for the ESA team to finally test it in practice.

The rate at which data is transferred from the rover to the spacecraft will start off at a relatively slow 8 kilobytes per second during the first test, before being gradually increased to 128 kilobytes per second over the remaining tests. This will help the ESA team evaluate the performance of the ‘blind’ data relay technique.

Preparations across Earth and the Solar System

To prepare for these tests, the Mars Express team first had to identify when the ESA spacecraft will be able see the Zhurong landing site. The Zhurong team then chose five of the best windows for relaying communications that fit well with their own mission operations planning.

Before the tests are carried out live in orbit, the teams want to ensure Mars Express and Zhurong can successfully communicate using both missions’ spare radios on Earth. Normally, this compatibility test would be carried out in person, but due to pandemic restrictions, the Zhurong team has not been able to travel to the spare Melacom radio unit in the UK at its manufacturer, QinetiQ.

As a work around, the Zhurong team has recorded a signal from their spare radio and sent it to the UK to be played back into the spare Melacom radio. The results of this test are expected soon. Combined with the general need for the teams to plan everything via online meetings across distant time zones, arranging this series of tests has required extra effort from all involved.

Timeline

The five tests have been booked in Mars Express’ mission planning system for the following times:

- Sunday 7 November, 12:07 – 12:17 UTC

- Tuesday 16 November, 19:34 – 19:44 UTC

- Thursday 18 November, 20:27 – 20:37 UTC

- Saturday 20 November, 21:20 – 21:27 UTC

- Monday 22 November, 22:13 – 22:22 UTC

The commands for each window will be uploaded to Mars Express one or two days beforehand. Data from the first test is expected to arrive on Earth roughly two hours after the window. A ‘dry run’ of uploading the commands Mars Express needs to carry out the data relay is planned for next week. There are currently no plans to perform any additional tests beyond the five planned in November.

Discussion: no comments