As we are constantly reminded, Christmas is fast approaching. Business, as we all know, has a finely-tuned understanding of how to use this season to its advantage, boosting turnover in the process. In our cities, twinkling lights are everywhere to be seen and the media is full of messages of Christmas cheer. For many, Christmas remains a very special time of year. Is it not interesting, therefore, that at times we see the words “Merry Christmas” substituted by “Happy Holidays” out of political correctness. Now I am all in favour of embracing all people regardless of their religious beliefs, but it surely makes no sense to turn a purely Christian event into a general party.

Earth and Moon, photographed by ESA astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti. This year’s Christmas Day (25 December 2015) will have a full moon for the first time in 38 years. Image credit: ESA/NASA.

There is a famous old story which I learned from a personal friend and great storyteller, Richard Martin (www.tellatale.eu). It shows that openness and religious beliefs are not in contradiction with each other and is actually very modern with respect to migration:

Milk and sugar

When the Zoroastrians*, suffering persecution from their conquerors from Persia (present-day Iran), fled to Sanjan on the west coast of India, they sought refuge from the local ruler, Jadi Rana. The great man called them before him and announced to the new arrivals: “We have no room for you here.” To illustrate his point, he had a vessel filled to the brim with milk.

“Each one of you we take in will cause this vessel to overflow”, he added.

At that point a Zoroastrian priest stepped forward, walked up to the vessel of milk and added a handful of sugar to it.

“If we come here, it is not to cause the milk to overflow”, he said, “but to sweeten it.”

Jadi Rana had no answer to that and so decided to allow the refugees to settle in his land. He offered them refuge but, in return, demanded that they adopt the language and dress of his people and made them promise to lay down their arms. He also left them free to practise their religion and observe their traditions unhindered.

You may watch Richard telling the full story here.

I hope that ESA, too, can demonstrate true openness and generosity of spirit and prove accepting of different beliefs and cultures, not only because it is a humanitarian necessity but because it sees diversity – in every sense of the word – as an opportunity.

I thank all those working at and for ESA for their wholehearted commitment and wish each and every one of you, dear readers, a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year!

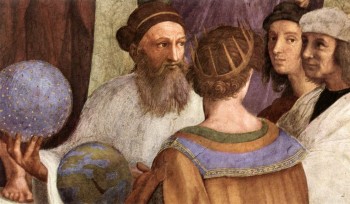

Zarathustra (left) as depicted in “The School of Athens”, one of the most famous frescoes by the Italian Renaissance artist Raphael. Image: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

*) Zarathustra (in Avestan, Zaraθuštra) lived at some time in the second or first millennium BC as an ancient Persian zaotar or priest. Zoroastrianism, the belief system that took his name, later established itself as a Persian-Median religion.

It is interesting to note that in two operatic works the figure of Zarathustra was brought to the stage. Handel‘s “dramma per musica”, Orlando, first performed in 1733, and based on the epic poem Orlando Furioso by Ariosto, features a wise magician by the name of Zoroastro. In Mozart’s The Magic Flute, first performed in 1791, the wise ruler Sarastro, with his council of priests, can be seen as representing humanist ideas. There is a clear link to be made between Handel’s Zoroastro, Mozart’s Sarastro and the Zarathustra, founder of a major world religion.

Discussion: 5 comments

It seems you have overlooked a broad history of holidays surrounding the winter solstice, an astronomical event I’m sure the ESA is well aware of. See for example

https://www.ibtimes.com/winter-solstice-2015-facts-about-pagan-yule-holidays-wicca-traditions-ties-christmas-2226814

or this

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/12/20/winter-solstice-2012-shortest-day-of-the-year-pagan-celebrations-photos_n_2340119.html

Greeting from Nova Scotia, Canada. What a fine post. I received the link to your blog on the Storytelling Listserver in a post by Richard Martin, whose work I admire greatly, but know only through the network and his CD’s. The husband of an old friend of mine works for the European Space Agency in Amsterdam. Stories connect everybody on the planet.

Thank you for the beautiful image of earth and moon, the excellent point about diversity, and the wonderful story about sweetening the milk. That’s a story I will borrow as I talk with people here in Scotland about welcoming more refugees here. I’m so pleased to see this kind of message from ESA. I expect it from one of my favourite clients (the UN’s World Food Programme) but it is good to know that ESA (another of my favourite clients) cares about our present as well as caring about our future. Thanks again.

Dear Jan,

I hope you are well. I would like to wish you and the ISS crew and the Principia mission astronauts a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year with this song I composed following the Dec. 15 launch. It is dedicated to them, their children and children around the world who will be inspired by this mission.

https://soundcloud.com/lullabies-connect/principia-space-mission-new-year-song

With best wishes!

Lyubov Pronina

Don’t forget that true Christian Christmas celebrations carry through January 6, the Epiphany, so “Happy Holidays” is appropriate for the many Christian holidays during this celebratory time.