Today’s blog post was contributed by Francesco Affaitati, from the flight dynamics team at ESOC supporting the Sentinel-2 mission.

The Sentinel-2B flight dynamics team are GREEN for launch!

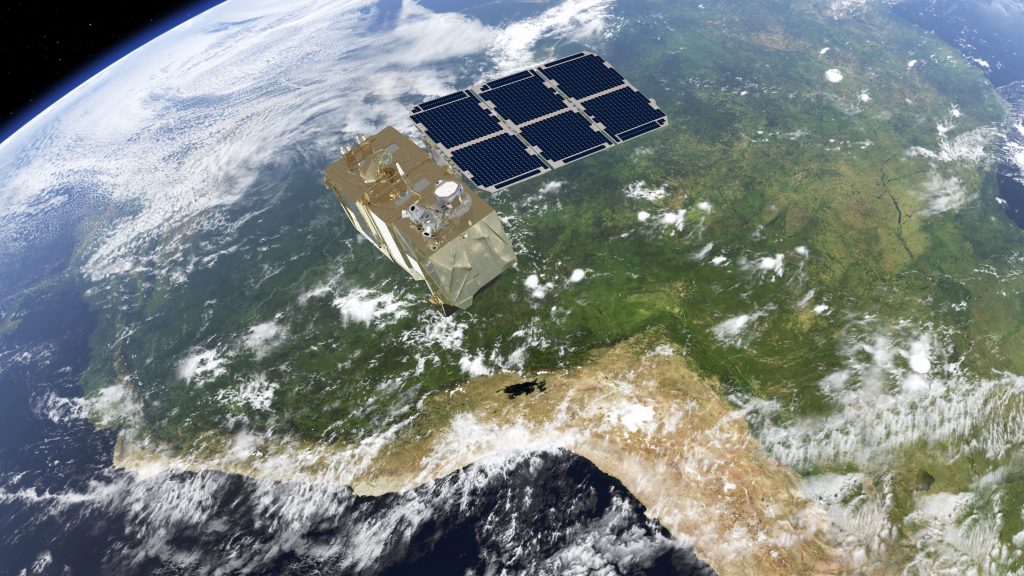

In addition to providing detailed information about Earth’s vegetation, Sentinel-2 is designed to play a key role in mapping differences in land cover to understand the landscape, map how it is used and monitor changes over time. Credit: ESA/ATG medialab

After months of preparation, integration tests and operational simulations, the flight dynamics system is now configured to support the launch on 7 March 2017 at 01:49 UTC (02:49 CET).

On that day, the second satellite of the Sentinel-2 dual-spacecraft mission, Sentinel-2B, will be injected into orbit to complete the constellation and shift the mission into high gear.

The Sentinel-2 mission comprises a constellation of two identical polar-orbiting satellites following the same ground track, and separated by an argument of latitude difference of 180°. The Sentinel-2 orbit cross the equator at a specific time of day (10:30 local) so as to guarantee the best illumination conditions for the optical acquisitions of the main instrument, the MSI.

About that launch window…

To achieve this orbit and target the 10:30 local time (when the satellite cross the equator while on the ‘downward’ arc of its orbit), the Vega launcher can lift off at only one moment in the day.

Vega launches from Europe’s Spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana, and is designed to be launched toward the north from Kourou, so as to facilitate recovery of the boosters over open ocean.

To calculate the lift-off time, various factors are taken into account, from the length of the ascending trajectory and the expected thrust performance of each Vega stage to the wind conditions. In case of any delay caused by a technical issue, even if it would only take a short time to fix, the next launch window opportunity will only come around 24 hours later.

The launch, of course, is just the start of operational activities for the flight dynamics team at ESA.

From the moment Vega lifts off, we will have to wait almost one hour until separation of the satellite from the Vega upper stage. At this point, we will begin conducting one of the most critical activities in any new mission: the first orbit determination, which will precisely identify the actual orbit of the satellite.

First ‘ODet’

In fact, a spacecraft is never perfectly injected into its designed trajectory, as any imprecision in launcher performance will be reflected in the spacecraft’s actual orbit. This is one reason why spacecraft are equipped with thrusters and propulsion systems, enabling them to be moved very precisely into a final orbit.

Animation of the constellation orbits 180° apart at 00:18 in this video

Contrary to the Sentinel-2A launch in 2015, this time the satellite will be injected into an orbit 11 km below the final, desired orbit (to avoid any risk of collision with the already-in-orbit twin!). Therefore, on top of the (never so) standard activities to correct the launcher orbit injection errors, which will keep us and the mission control team busy for three days around the clock, we will have to plan for a ‘raising manoeuvre sequence’ in order to bring the satellite into its final orbit.

This is not a trivial activity, as, at the same time, we have to also ensure that the spacecraft can be properly tracked by the ground station antennas (i.e. that the antenna operators know exactly where to point the antenna before each communication slot), cope with any uncertainties that a new spacecraft not-yet-fully commissioned may give, handle any uncertainties that the space environment throws at us and – last but not least – be ready to deal with space debris.

We are really looking forward to this launch, and to being part of the larger ‘team of teams’ working to complete the Sentinel-2 constellation. We are proud to support Copernicus and the European Commission!

Sentinel-2B FDyn Team – and they’re great with Photoshop, too! Credit: ESA

Discussion: one comment

WOW! There’s a lot of ‘needs to happen at the right time’ type of events enveloping this mission.