Dr. Nadja Albertsen is the ESA-sponsored medical doctor spending 12 months at Concordia research station in Antarctica. She facilitates a number of experiments on the effects of isolation, light deprivation, and extreme temperatures on the human body and mind. In the following post, Nadja walks us through a day in the life of Concordia.

Then it was March.

The light changes almost daily. It is still bright out, but the evenings are beginning to darken and the sun disappears behind the horizon, leaving a cool orange and blue-green shade over the ice. There are still very few stars and planets to be seen in the evening – but they shine brighter and clearer and the temperature is now almost a constant –60°C, even on calm days. The layer of ice on my window is gradually becoming so thick that it does not melt during the day.

North of the equator the opposite is happening. Friends and family send pictures of spring flowers in Denmark, flowering peach trees in southern France and walks in Italy. I love the photos but they contribute to the sense of surrealism that can catch you off guard. Imagine being here, where conditions dictate that no people should be, where you can currently take a (comfortable) walk in –70°C and afterwards drink espresso made from freshly ground beans.

You have to remind yourself of how special it is to be here. And, also, to remember to be here: enjoy the total, unique silence rather than waste time missing the sounds of morning or rain falling.

As the days here and in Europe go by, we are already in the process of finding our replacements. We talk of what will happen in the autumn when our time here runs out, about holidays, work, PhD projects, housing and families.

It’s funny that humans are often moving on before we even take off our Concordia boots.

A few weeks ago we had our first winter full moon. And not only that, it was a very beautiful super full moon. To view it, our astronomer just had to figure out when the moon would rise, and it turned out to be more complicated process!

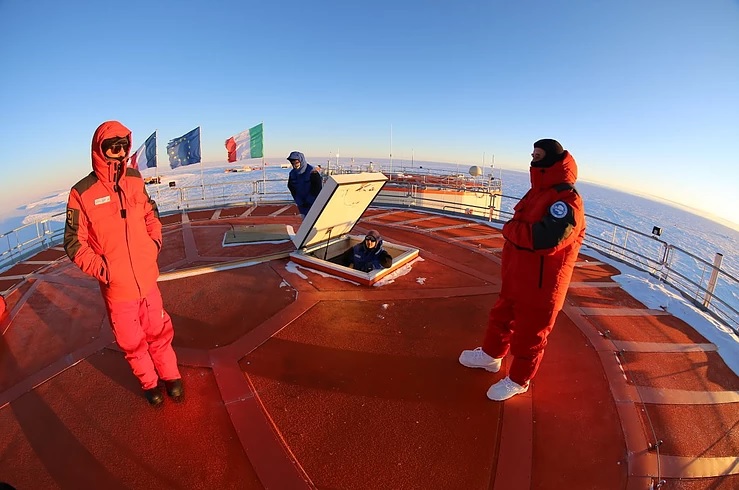

He came up with one time, then later in the day another, and finally got confused and had to start calculating all over again. In the end we managed to stand outside on the roof of the base one hour early, freezing, but it was mostly for fun for everyone.

The time was not the only challenge; we also had to find out WHERE the moon would rise. And this is where we were quite fortunate to be on the roof early enough to catch the sunset. When the moon is full, it stands directly opposite the sun, whose rays fully illuminate its Earth-facing side. During a super full moon, the moon is at its closest point to Earth, allowing Earth’s atmosphere to deflect blue light so that only the red spectrum of light appears. As the moon rises higher in the sky, and the atmosphere no longer distorts the Sun’s light, the moon returns to its “normal” luminous white/yellow.

One could argue that we could have used a compass to guide us, but it’s actually a little tricky to find those ‘world corners’ when you’re close to the poles.

On each side of the equator we have three poles – the geographical, the magnetic and the geomagnetic.

The geographic South Pole is the pole that Roald Amundsen reached first in 1911, in a close race against Englishman Robert Scott. The geographic South Pole marks the southern point of the axis around which the earth rotates and the point is fixed at 90 degrees south latitude. Today there is an American base there. If you dig a hole deep enough through the core of the earth, you would reach the geographic North Pole – they are opposite each other.

The magnetic South Pole and North Pole are in constant motion, as they follow Earth’s magnetic field, determined by the moving liquid iron content at Earth’s core.

Every year the poles move up to 10 km, and the North Pole has previously been south of the equator and vice versa! Unlike the geographic poles, they are not opposite each other. If you draw a line from one pole through the core of the earth, then you hit the corresponding magnetic pole. As if this were not tricky enough, the magnetic South Pole is actually the magnetic North Pole as it attracts the south end of the compass, because, as you know, opposites attract.

The compass needles are attracted to the magnetic poles, so the closer a compass gets to them, the more inaccurate it is relative to the geographic poles. In fact, a compass can become so disturbed by the magnetic fields that you can’t use it for much.

Hooray for global navigation systems!

In the end, we managed to use the sunset as a guide and saw the most beautiful moon.

As a bonus we also got minor frostbite thanks to the long wait and a healthy scepticism for our astronomer’s calculations.

Otherwise, we are fairly established in our daily lives here at the base. The pace is slower compared to the summer period, and we each have our own rhythm, which are more pronounced now than before. The mood is good, despite the fact that, due to language and culture, still – and probably always – there is a small division between the French and Italian participants. I have a leg in both camps and still speak German with the chef – and it works great.

Happy Spring for you all – remember to enjoy it while it lasts. Maybe you will be in Antarctica next year and then you will miss it!

To read Nadja’s adventures at Concordia in Danish, see her personal blog.

Discussion: no comments